Jagdish Chandra Jai, alias U Swetin, and his family were amongst the hundreds of Burmese Indians who traversed all the way from the city of Taunggyi to Delhi, in the early 1970s. A praetorian regime can have a number of implications for a state and its people, but for the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, the working, yielding Indian immigrant was historically one of the worst wounded.

Jai was a merchant and the heir of a familial estate dating back to the early 1900s. He was a staunch revolutionary for Burmese democracy, a cause espoused by leader Aung San and later his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi. A unilateral military coup led by General Ne Win, coupled with his policy of aggressive socialism, brought the Jais to their knees; their property and businesses nationalised and resources standing seized. This economic ruin, paralleled by the iron-hand campaign against Indians and dissidents, left the Jais no alternative but to flee to Delhi, hustling to rescue a calamitous fate.

An estimated 300,000 Indians, who had primarily inhabited Burma, in mercantile, banking and agricultural occupations, at the dawn of the 1920s and ‘30s, faced at least two ousters in a thin span of two decades at the behest of forces much beyond their influence. While some claim the Indian community was merely a victim of collateral damage, others theorise, as a matter of fact, that the ethno-nationalist forces among the Bamars were sewing plumes of hostility against the community for decades. It was at the peak of the 1930s that the smoke first emblazoned against the existing Indian community in pockets of Rangoon and Mandalay. Post 1937, when the British government in India declared the Burma Province a separate colony, a number of anti-Indian riots in these major cities, including the unforgettable Dockyard Riots, killed thousands.These also led to the dismantling of private property leaving a multitude of Indians to fend for themselves.

Lala Girdhari Lal Jai, the patriarch of the Jai family, was amongst the first generations of traditional zamindars in Kapurthala, to resettle as a merchant of the meticulous and far-spread trade of gemstones and oil in the Shan State. His demise in the later half of the 1930s left sons Harish and Jagdish with the baggage of ancestral legacy. Meanwhile, the nebulous clouds of the Second World War had started to obscure Burma’s fragile terrain. The Jais recall the early days of the Japanese occupation as those marked by regular bombardments in zones of civilian residence, long days of confinement, and their homeland rife with the fears of selective targeting and an inevitable exodus of the people of Indian descent.

The first wave of expulsions began thus, with more than 15,000 Indians leaving Burma in the early phase, and with the coming of the Japanese invaders, a state-ordered evacuation drive took its force transporting almost a lakh back to India. While the journey by itself was harangued by a conspicuous racial divide between the ‘kalur’ Indian and the British, both escaping foreseeable doom at the hand of the Japanese, graver wounds could be attributed to a skewed administrative mechanism. The lawless clamour led to over two-lakh more walking through a disoriented corridor back to India, with the number of deaths along the Taungup route unascertained to this day.

Based out of Lahore, government contractor Des Raj Chopra was one of those quick to foresee the horrors of a late and unregulated deportation. Leaving his home in Mandalay with his family by sea for the shores in Calcutta, the Chopras turned towards their home in undivided Punjab, until the fatal turn of events would send for them the macabre violence of the Partition of India in 1947 – an affliction shared by millions, but theirs was a story in distinction. While other Punjabis in Lahore moved inwards to the Indian Punjab and onwards to Delhi, the Chopras boarded a train to Calcutta, back ashore to Mandalay, as if the requiem for a home kept lulling them to pay a visit.

The following years were those of sheer uncertainty, for close to four lakh Indians who either returned to the land or never chose to leave despite the atmospheric hardship. General Aung San, the father of the Burmese nation was assassinated with his cabinet in 1947, but the Union of Burma, led by his successor and the first Prime Minister, U Nu, attained its hard-fought independence and became a democratic republic. For the time, winds blew in favour of a steady restoration of internal stability. But less than two years after the reformation of U Nu’s party, the AFPL, as the Union Party, and his subsequent election triumph, the government was toppled by the infamous Burmese coup d’état in March, 1962. The pallbearer of this momentous spin, General Ne Win fostered the grand idea of “the Burmese Road to Socialism”, and hand in glove with that, the policy of political detentions.

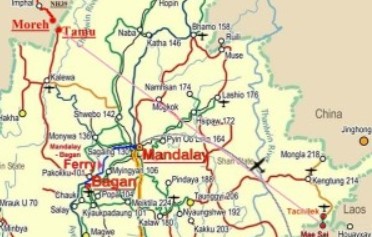

It was in the months that followed that politically active youth, those of the coven of the Indian community, were sentenced to house arrests. A phased campaign of Indian expulsion then began in quick succession. Most immovable property, including houses, businesses, offices, schools, cinema halls, temples, and other zones of social and economic life, were found besieged by the military under what is now known as the most anti-Indian measure of the day– the Enterprises Nationalization Act of 1963. Indians, now carefully scrutinising an array of options at their disposal, started to flee the country eastwards, in spurts, by the 1960s. Jai’s extended family first landed in Central Delhi in 1964 and then found business in the enclaves of Moreh, Manipur in the early ‘70s. About a lakh Indians fled Burma in 1964, while most of them, including Prime Minister U Nu were given asylum by the erstwhile Indian government.

At its core, the Jai-Chopra family perhaps chose to wait, witness how the nation would decide to embrace its people back into its fold. That, however, never happened. With debilitated finances, and the resistance against the forceful uprooting seeing the face of failure, a part of the family was compelled to follow its Indian predecessors and move to Delhi in around 1971, and again to the town of Moreh, where it found solace in the composite cradle of a welcoming Tamilian, Bihari, Marwari, Nepali, along with a meagre Punjabi community – people who had earlier been helpless and unhinged with a sudden rise in temperament against their presence back in, what was now called, Myanmar.

By 1976, more than two lakh Indians had left Myanmar for India, Thailand, Singapore, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Western civilisation. The Government of India embraced the Burmese people of Indian origins in its massive repatriation and integration drive till about 1987 and constituted a number of ‘Burma Colonies’ across states key recipients of the population. A retrospective analysis would show, however, that most of these colonies beyond New Delhi, Manipur, and Tamil Nadu, were lost in the broader vision of development.

Families across India recall their days in Burma, with memories of strife, struggle, but also clear fondness for what they lived and lost in a singular lifetime. The minuscule Indian community, including the extended Jai-Chopra family, still persisting against the likelihood of perish in present-day Myanmar, spectates the recent tussle between the military and Suu Kyi’s democratic government in apprehension, but admits of having seen worse. The next generation Jais visit the lost homeland, now as tourists. Their dwelling in Taunggyi stands erect, albeit painted all blue, like all the other houses in the region– the colour never failing to grip their senses with the melancholy it symbolises.

Samridhi Chugh is a final-year student of Journalism with Political Science at Lady Shri Ram College for Women.

Interested in exploring the confluence of law, policy and print media, she tends to use the written word as a conduit for her scattered emotions.

She aspires to pursue legal journalism at a near future.

Hi there! This is kind of off topic but I need some advice from an established

blog. Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not

very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick.

I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to start.

Do you have any tips or suggestions? Thanks