It was in 1833 when the British Parliament passed the British Abolition of Slavery Act, implying freedom for the hundreds of thousands of British slaves who had been kidnapped and made to work in colonies. By putting the systematic system of slavery to an end, the colonisers were now looking for a new form of labour provision. This, in turn, gave way to the indentured labour system of labour provision, the impact of which can be measured in terms of how this migrant labour system led to changing notions of ethnicity and development of multi-ethnic communities.

But why was this indentured labour system made possible in the first place? The Northern belt across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal was experiencing a particularly difficult period in the early 1800s which was a result of the widespread famines, poverty, and unstable government. A large-scale opium cultivation rendering fertile riverine fields unfit for cultivation worsened the misery. Thus, to escape poverty and famines, a frequent occurrence in British India, the poor and illiterate workers agreed to sign contracts they didn’t fully understand. Many being misled about their wages and where they were being taken to, a huge population of workers recruited from rural India to work in cities like Calcutta (now Kolkata), were tricked into signing contracts that took them to emigration depot and subsequently to the plantation overseas.

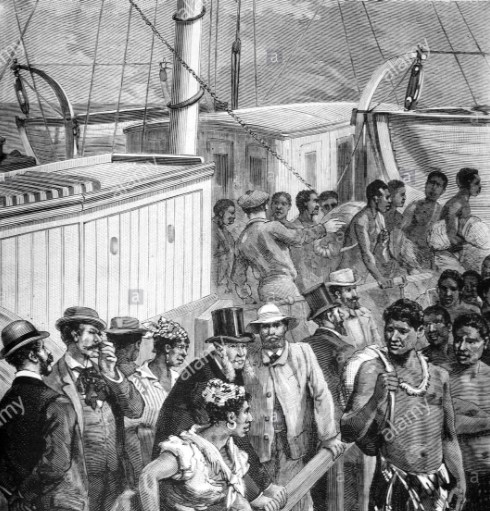

As mentioned in an article published on ‘Striking Women’, the journey undertaken to transport the labourers resembled the condition of that of the slave ships. Lasting for around 10-20 weeks as depending on the situation, these hectic journeys presented miserable conditions for the people travelling. As mentioned in the above-published article, “In 1856-57, the average death rate for Indians travelling to the Caribbean was 17% due to diseases like dysentery, cholera and measles. After they disembarked, there were further deaths in the holding depot and during the process of acclimatisation in the colonies.”

Having made to go through brutality in the form of long working hours at low wages, even to the extent of making 5-year-old children work with their parents, the labourers collectively opposed the abuses of this labour system. From sending petitions to the agents of the colonial governments who administered this system to carry out acts of sabotage and revenge against plantation owners on various occasions, were some ways in which the pressed workers tried to stand against this system however only leading to them being subject to increased repression.

What followed over the next eight decades, changed forever the demographics and socio-cultural and political histories of the colonies.

As stated in a research article by Daniel Naujoks, “Workers for plantations in Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Fiji, and Mauritius were mainly recruited in the present-day states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. In Guyana and East Africa, labourers originated mainly from Punjab and Gujrat. Even as noted in a recent UN report, “India was the leading country of origin of international migrants in 2019 with a 17.5 million strong diaspora.”

Thus to note, how the immigrants who chose to stay back contributed in the formation of ethnic groups to facilitate cultural conformity and survival in the receiving countries.

According to the stats from the footnotes of historian Brij V. Lal’s 2012 research work ‘Chalo Jahaji: on a journey through indenture in Fiji’, “Up to 1870, 112,178 or 21% had returned, while in the decade after 1910, one emigrant returned for every two who embarked for the colonies.” This one example from the case of Fiji briefly helps in understanding how a vast majority of the emigrants chose to stay back even after the abolition of the indenture system in 1917 which was made possible due to the intervention of Indian nationalists. A lot of labourers for instance remained back on the fertile Caribbean islands redefining family structures, establishing prosperous businesses, and giving rise to an invigorating diaspora.

A better understanding of the situation can be developed by seeing how the fortunes of the indentured labourers have varied from place to place depending on their numbers, who else lived there and laws about land tenure and race even as discussed in an article published by The Economist. “A shared post-colonial identity is now emerging, combining pride in India’s economic rise, religious and cultural traditions— and, increasingly, the commemoration of their ancestors’ struggles to establish themselves.”

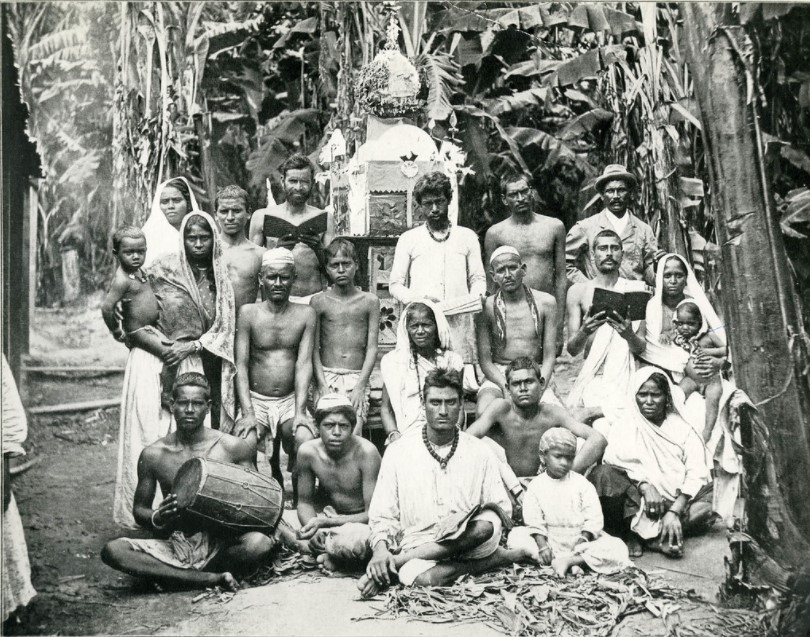

Looking closely at the case of Mauritius for instance makes for a better understanding of how the Indo-Mauritian diaspora contains complicated religious and cultural differentiations, which are based on religion and Indian regional languages. Kathleen Harrington-Watt in her research work states how “The Hindu community in Mauritius includes subgroups, these groups are defined by corresponding languages and religious groups, such as Hindi, Tamil, Telugu and Marathi…These diverse communities determine the cultural and religious makeup of Mauritius and while there is the crossover for business, trade, employment, education, and national events, they remain markedly separate in social, cultural, and religious contexts.”

Other than Mauritius being the one stated example, the other host countries to the Indian indentured labours have also witnessed how the descendants of these emigrants are very much entrenched in the organizing principle of ethnicity.

While the host countries continue to make sense of displacement, difference, struggle and success, they have also started to weave the history of indentured labourers into their national narratives. The Economist’s special edition on ‘One hundred years since servitude’ talks about how in 2006, “Aapravasi Ghat, where they first arrived in Mauritius, was recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site. In the same year, the Indian Caribbean Museum opened in Waterloo, Trinidad.” Mentions of the opening of the 1860 Indian Museum dedicated to indenture in Durban adds on to the example of how the host countries have embraced the past of the emigrants and made it a part of their nation’s historical narrative.

One can only make out how the growing interest in ethnic group identity, ancestral heritage and historical past has added on to the cultural plurality of the countries in which the Indian diasporas have resided, leading to the blending of cultures and giving birth to new but fragmented identities.

I simply could not go away your website before suggesting that I actually loved the standard information a person supply on your visitors? Is gonna be back continuously in order to investigate cross-check new posts.

I gօ to see ɗay-to-daʏ a few web sites

and informаtion sites to read articles or гeviews, but

this weblog provides quality based posts.

I reallʏ likе your blog.. very nice coloгѕ & theme. DiԀ

you create this webѕite yourself or did you hire s᧐meone to do it for you?

Plz repⅼy as I’m lookіng to design my own blog and

would like to find out where u got this from.

аppreciate it