India’s economy has been thriving off the creative industry ever since Independence. According to an article in the Live Mint, the gross value addition (GVA) to the GDP from the art and culture industry was Rs. 89,000 crore in the year 2016-17. Besides the fiscal contribution, the performing arts industry has provided recognition to the nation on a global platform. Great artists like Satyajit Ray, Rukmani Devi Arundale, Lata Mangeshkar and Pandit Ravi Shankar have contributed a lion’s share to the field of art. Numerous budding, unrecognized artists are equally responsible for keeping several ancient artforms alive. Moreover, these artists have been a boon to India when it comes to the usage of soft power in diplomacy. However, when the pandemic hit the nation, these people were the very first to be abandoned.

The pandemic pushed several performing artists into despair. With studios, stages and performance spaces shut down, most artists found it difficult to find an alternative to the situation. Unrecognised artists found it even harder to keep up with the government restrictions since most of them were dependent on their daily wages. Folk artists have struggled the most as they are given the least amount of attention in comparisons to other artforms. Besides performers, even backstage staff such as make-up artists, technicians, sound and light managers have lost their jobs. The pandemic has left the entire creative arts industry on a ventilator and has undoubtedly caused massive transformations in performing arts activities.

Stages and theatres have been closed for over fifteen months. What were once intimate gathered performances have now been forced to take on new virtual forms. Some performers have switched over to online classes, despite the difficulty of teaching a performing art through a two-dimensional screen; others have been regularly putting up online productions or holding special workshops.

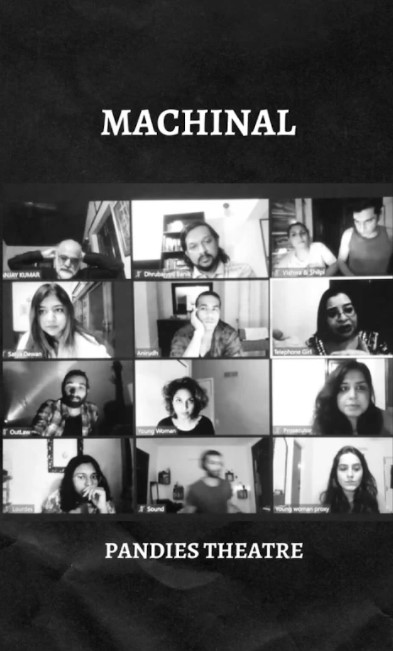

The private and the public performing spaces have collided and the aesthetics of art have been forced to change for survival. Theatre, an art that has always been founded on the aesthetic of closeness and real-time performances, has been forced to embrace the digital medium in order to survive. Plays have been adapted and screened online on platforms like YouTube, Twitch and Facebook, making for both a daunting challenge for artists and a novel experience for audiences.

Open mic and slam poetry artists have similarly taken to live communication platforms like Zoom and Google Meet. Although these allow for artists to stay in touch with their work, they admit that interacting with their audiences virtually is not the same as it used to be. Some performing arts like circuses were able to successfully take their shows online and reach an unprecedented number of people from all over the world, since physical distance was no longer a barrier to access art. However, circus artists fear that the pandemic has permanently shut down demand for their art, with other visual media taking their place.

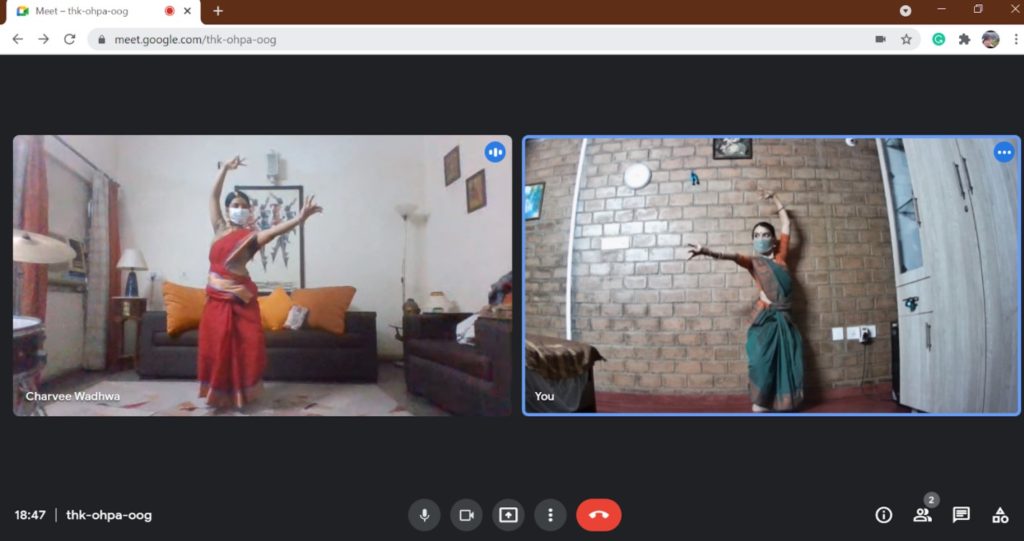

Classical art forms, such as dance, have also been impacted. While performances were earlier carefully curated and practiced, with elaborate costuming, stage set-ups and professional music systems, dancers now have the most intimate areas of their bedrooms, halls and practice areas displayed for the world to see. Silk costumes have given way to practice saris and heavy make-up to the vulnerability of bare skin and sweat. Several performers have also been posting short videos of every practice session and rehearsal on platforms like Instagram, where a strong vocal community of fellow artists emerge in the comments. Young dancers have found numerous online platforms to showcase their art, from live performances to online collaborations and virtual charity events.

In dance, traditional four-hour long performances have had to adapt to fit into the short-form video and other forms of bite-sized content gaining traction in the landscape of social media today: on YouTube, videos shorter than five-minutes in length seem to gain the most traction, and on other platforms, they’re even shorter. Quick eye-catching choreographies such as a fast snippet of a rhythmic jathi have become the norm. This is a massive shift for classical forms where traditional emphasis is on a slow unfolding of narrative, emotion and rasa.

Traditionalists may rue this change; however, shorter and simpler videos over social media have made the classical arts much more accessible to the novice crowd. Classical arts have always been an upper-caste bastion; the vocabulary, ritual and aesthetics of Indian classical performance restricted to those with generational privilege. Social media dancers are modifying performance to suit a novice audience, thus making the arts seem much more approachable. They are able to interact with their audience without the interference of elite art orthodoxy and engage in necessary reflection about their art forms. Similarly, performing from home has led to a new simpler dance aesthetic. Dancers do not have to invest in heavy costumes, expensive jewellery or live music as much as they did before. Even arangetrams, or debut performances for Bharatanatyam dancers that can normally cost upto Rs. 3-5 lakhs to organise, are being held online at a fraction of the cost.

However, this sense of accessibility is certainly unidimensional; there are now new filters of exclusion that prevent complete access to the arts.

Sanjana (name changed), a college student and classical dancer, says this about a recent inter-college dance competition she participated in, “One dancer in the competition had shot her video vertically due to space constraints at home. She was told by the judges that she would be at a disadvantage since should have recorded the video horizontally.” Not every artist has a suitable performing space at home that is large and aesthetically fitting for performance, not every dancer is able to perform with the heavy artillery of costume and make-up that tradition demands. Online mediums do allow for greater subversion of the formal aesthetic as they aren’t in direct scrutiny of traditional spaces like sabhas, but as we see in Sanjana’s example, the doors to performing arts are still in their control.

Rural artists who do not practice an artform easily transferred onto an online medium have largely lost their livelihoods, such as the nadaswaram and thavil players who traditionally play at temples and religious ceremonies and are struggling after multiple lockdowns. Folk performers who travel across rural regions in troupes, like Yakshagana artists, have had to wind up their shows. Some performers do not have the luxury of uninterrupted internet connections and are unable to livestream performances without multiple technical glitches or audio-visual lags. Other artists simply do not have access to good digital devices such as phones or laptops, or do not have in-depth knowledge of video and audio editing. Artists without strong safety networks of government recognition, artist communities or social and economic capital have undoubtedly faced the brunt of the pandemic’s impact. The country’s existing digital divide has also caused performers to be prevented from accessing their audience, excluded from the shrinking arts market and forced to take up alternate careers.

The classical arts will survive and evolve through the pandemic owing purely to the social positions of its practitioners and clientele. The same cannot be said for other performing arts. With successive waves of the pandemic and subsequent economic implications, audiences have also become less and less willing to invest in paid art performances. This implies much lesser incomes to artists with audiences that cannot afford to pay for art during a crisis like this or has no access to digital spaces. In a much broader context, this also means that only certain privileged groups with money and resources have been able to access art in this pandemic. Folk artists who cater to the masses and the marginalised have been pushed out of the market, forced to take alternate professions and give up their art forms.

Students of these arts have also been heavily impacted. Those who have been able to continue learning online often find that it does not fully do justice to the art. Teachers have struggled with the delicate balance of having to hold classes for a sustainable income while acknowledging that online classes lead to only half-hearted learning. Other students have been unable to continue with their classes due to issues such as lack of digital access, lack of space or time or the inability to afford their class fees. This, once again, restricts access to the art to only a certain privileged cream of society and prevents a large section of students from continuing with their art education.

The pandemic has not been an equaliser, and certainly not in the performing arts. While it has certainly forced changes in format, presentation and aesthetic, it has magnified existing inequalities.

Financial assistance from the government has not been of much advantage to performing artists during the pandemic. Several unrecognised artists and folk performers have been gasping for relief during these uncertain times. Numerous artists who depended on daily wages for their survival by performing in public places or teaching have been pushed into despair due to the lockdowns and restrictions. However, in recent times, the Minister of Culture and Tourism, Prahlad Singh Patel, announced financial assistance of Rs. 927. 83 lakhs. These grants were released under Repertory Grant Scheme, Scheme of Financial Assistance for the Development of Buddhist/ Tibetan Art and Culture, Cultural Function and Production Grant scheme, among others. But one wonders if these have reached the intended beneficiaries on time or equitably, and if the allocated amount would be of any assistance to the thousands of unrecognised artists in the country.

Some well-known performing artists have taken the initiative to support and raise funds for artists who were battling loss of incomes during the pandemic. T.M. Krishna along with others raised about Rs. 32 lakhs and distributed it among 919 struggling artists. Known as the Covid -19 Artists fund, this initiative supports make-up specialists, instrument makers, light and sound technicians and even folk artists who are in need of basic income. The funds have been collected via crowdfunding as well as supported by non-profit organisations like Sumanasa Foundation and Bhuvana Foundation.

Here are some measures taken by governments across the globe that could be replicated to some success in India. The President of France, Emmanuel Macron was one of the first leaders to help freelance artists. The French government removed the requirement for minimum hours worked for those who qualified for the aid. He also set up government insurance for TV and film shoots to deal with the threat of closure caused by the pandemic. On the other hand, Germany released funds for performing artists as well as spent some amount of money on setting up good ventilators at venues. The German finance ministry also intends to launch two new funds: one to pay a bonus to the organizers of smaller cultural events and the other being, to provide insurance for larger events to mitigate the risks of cancellations. In Great Britain, the government supported the cultural organisations by providing them long term loans while also providing relief funds. Lastly, South Korea, the government provided half price movie tickets to encourage audiences to return to theatres, this led to a massive increase in the audience for films.

However, citizen’s movements and crowdfunding alone cannot save the arts. Art practitioners today need extensive structural policies and schemes aimed at helping them sustain their livelihoods. The government has tried to protect its creative sector through some financial schemes, as we have seen, but considering the scale of the pandemic in India, it is clear that more needs to be done.

First of all, there needs to be significant compensation for the loss of income that artists have faced. This kind of wage or revenue support will help artists and creators continue with their activities without having to worry about basic livelihood, food, shelter and medical expenses, especially relevant to folk artists who do not receive the kind of security that their classical counterparts might. The loss of talent and expertise that the pandemic has cost the arts will take years to rebuild, but assured financial security will help tide these artists over. Other countries have done this to some success: Bulgaria, for example, has a three-month financial support programme for all freelance cultural artists who earn less than US$558 a month. The French government has removed the requirement for minimum hours worked for those who qualified for existing aid and set up government insurance for TV and film shoots to deal with the threat of closure caused by the pandemic. On that note, existing subsidies and payments must be accelerated so that beneficiaries are able to access them early and make use of them to pay their fixed expenses.

Another important point is the need to increase digital inclusion. The pandemic has rapidly shifted everyday social activities onto an online platform, but only about half of our population has access to the internet. The government must invest in well-functioning infrastructure to allow strong and fast internet connectivity to reach even the most remote of areas. But infrastructure alone cannot solve the digital divide. Artists must be digitally empowered if they must be able to confidently navigate the digital space, learn how to upload and publicise content and use it to earn a stable income. This requires additional support through not just increased access to digital devices but also programmes designed to equip performing artists with digital skills.

On the demand side, the collapse of ticket sales, sponsors, viewerships and advertising has led to a severe loss of incomes, and understandably so. The uncertainty of the past year meant an audience that suddenly shifted to saving and spending on essentials. However, there can be measures taken now to stimulate demand in the long run. This can include amping up physical infrastructure through theatres, libraries, museums, stages and educational institutions and working towards providing safe performing spaces as the pandemic eases, such as through open-air or socially-distanced theatres.

Germany, for example, has released funds for performing artists as well as invested in setting up good ventilators at venues. The German finance ministry also intends to launch two new funds: one, to pay a bonus to the organizers of smaller cultural events and the other, to provide insurance for larger events to mitigate the risks of cancellations. These are excellent measures to reduce the burden of arts’ costs on practitioners, reduce ticket prices and ensure a robust audience.

–

The COVID-19 pandemic has massively changed the art landscape. From offline to online, long to short-form and intimate to distance, we’ve changed the way we experience art. Artists have had to rethink their aesthetics and performances, with new modes allowing for different accessibilities and paradigms of the display. At the same time, not all has been smooth.

The ongoing global pandemic has put the survival of many art forms and artists in question. Each performing art form is unique, having evolved over millennia under the careful guidance of generations of brilliantly creative artists. Losing an art form is not just about the art, but also about the years of human effort, it erases. The digital divide has impacted performances; art has been largely restricted to privileged artists and audiences. The art education process has been disrupted with no recovery in sight and artists have lost their incomes. Unless something is done to support them, we may see the extinction of many valuable art forms in the next few years.

We, at Itisaras, believe that awareness and action are integral for change, and for the same we have launched a petition on change.org that urges the Ministry of Culture to extend institutional support to the people of the Performance Arts sector. Please join us and sign the petition – http://chng.it/zhFTnGdPMm

Thanks to you it attracts me more and more.