By Debopriya Bhattacharya

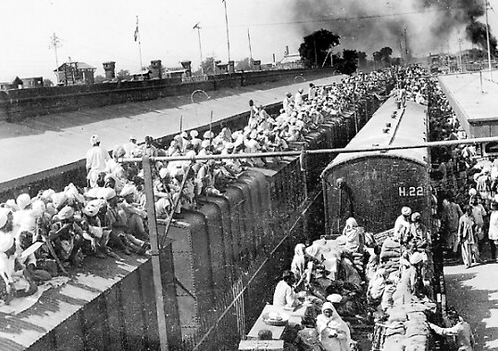

August 15th, 1947 saw the culmination of a socio-political process that began in the year 1857, with India’s first war of independence against colonial rule. Partition of India “was the ‘last-minute’ mechanism by which the British were able to secure agreement over how independence would take place.” Leading to the division of British India into two separate states of India and Pakistan, partition, as written by the acclaimed Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal, is “A defining moment that is neither beginning nor end, the partition continues to influence how the peoples and states of post-colonial South Asia envisage their past, present and future.”

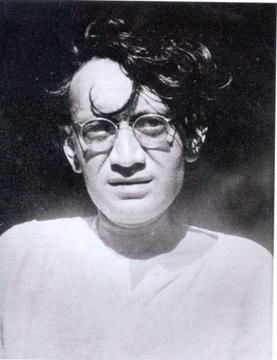

An episode that affected the lives of about 10-12 million people, the Partition of India is seen to have left an impact on human emotions to an extent that influenced artists. While literature produced during this time discussed the political consequences of the partition, some writers were writing about the barbarism of the event. Among them was Saadat Hasan Manto, “the voice of all those who were stranded between conflicting identities”, as Scroll writes.

To quote from one of the letters, Manto addressed to his close friend and writer, Ismat Chughtai, “Try as I did, I wasn’t able to separate Pakistan from India and India from Pakistan. Again and again, troubling questions rang in my mind: Will Pakistan’s literature be separate from that of India’s? If so, how? Who owns all that was written in undivided India? Will that be partitioned too?”

Known to be remarkable reflections of the human behaviour that carried the trauma of the Partition, Manto’s stories became the window that gave a clear view of the human suffering caused due to this upheaval.

His characters came to be recognized as the representation of the psychological horror and the torn identities caused by partition riots that separated them from their native places. In Zaheda Hina’s words, “Manto internalised the pain of Partition, not as a Muslim, Hindu or Sikh or as a speaker of Urdu, Punjabi or Marathi but as a human being, and was shattered in the process.”

His stories held a mirror to the society, reflecting the reality that followed the riots of Partition which Manto identified as an “overwhelming tragedy” and “maddeningly senseless”.

Known to be one of his most famous works, ‘Toba Tek Singh’ raises questions on the idea of nationhood as a means to define the identity of an individual. Describing the exchange of the inmates of a mental asylum in Lahore, the story reflects the madness and absurdity of the outside world using the madness of the inmates of the asylum as a symbol. Using its protagonist, Bishan Singh, as an embodiment of ‘those who were stranded between conflicting identities’, this powerful satire brings to fore the suffering of the partition refugees. Being unable to make a choice between which country is his homeland, Bishan Singh chooses to die in no man’s land and this, in turn, brings forward to the readers the idea of ‘fractured identities’ and ‘loss of sense of belonging’ reinforced by the pain and emotional trauma of displacement.

Yet another theme which was prevalent in Manto’s stories was how he called out the acts of misogyny committed in the name of nationalism and communal honour, as Maryam Mansoor writes. To quote from an article by The Friday Times, “Women and their stories become literary devices for Manto to reaffirm and reiterate his humanistic vision.” In fact, it was Manto’s realistic portrayal of his characters and their stories that presented the real picture of a subcontinent under the crisis of religious riots.

To say, Manto was ahead of his time when he wrote about violence committed against women during the Partition. Intertwined in the complex cycle of social marginalization and taboo, women during partition were subjected to various atrocities, that Manto thought was important to uncover using his frank treatment of sex and sexuality. It was Manto’s way of lifting the curtain off the existing hypocrisy.

By simply labelling the sensitive and existing issues as obscene and escaping the reality was what Manto was against. In the words of Ayesha Jalal, “Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps or criminals, Manto wanted to impress upon his readers that these disreputable people were also human, much more than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy.”

The images of savagery in ‘Thanda Gosht’ and ‘Khol Do’ that leaves jarring imprints on a reader’s mind helps to bring through the motive Manto was trying to achieve through his writings, a real portrayal of how women were abused in the backdrop of what was deemed as a secure agreement over how independence would take place or how Raza Rumi writes, “his (Manto) work redefines long-held patriarchal notions of vulgarity and taboo through teaming up humanism with taboo.”

However, Manto’s critique of a harmonious society turned bloodthirsty, was not well received by his critics, which is why he was tried for obscenity in his writings several times. His idea of juxtaposing the gang rape of a woman with that of humanity in his story ‘Khol Do’ and the rape of a corpse to symbolize how the exertion of power extended not just to women but adversely affected other members in the community in his story ‘Thanda Gosht’, was often seen in terms of presenting an obscene portrayal of the society that Manto conceived to be the reality.

Manto’s different approach towards Partition trauma and the underlying sense of reality in his stories make his writings seminal in understanding the consequences of the Partition. Having achieved the ability to recreate and understand the human suffering in such depth, makes Manto’s contribution to Partition literature remarkable.