The collection and inclusion of caste data in the national census have been in debate for quite some time in the socio-political sphere. In the 2011 Census of India, there were questions about caste for the first time since Indian independence. While the move of the then United Progressive Alliance (UPA), was supported by notable OBC leaders such as Lalu Prasad Yadav, Mulayam Singh Yadav, and Nitish Kumar, there was much debate both for and against it, and eventually, details of castes were not made public with the release of other census data, explained to be due to inaccuracies in collected data.

Scholar and human rights activist Gail Omvedt notes that there was much resentment against this inclusion of caste in the census. The elites and upper castes, in specific, believed that the collection of caste data would only lead to increasing vote-bank and reservation politics. Some argued that caste was not homogenous across the country and raised questions about how inter-caste families would be included in this caste census. The other voices in this debate were the loud elite ones that claimed that it would be more suitable for a census to count economic depravity rather than caste.

Some of this apprehension, Omvedt believes, arises from the treatment of caste under colonial rule. In 1901, the British ethnographer and administrator Herbert Risley undertook his famous mission to document caste- and in doing so, he ranked castes in a hierarchy that he based on social norms, the varna theory, and his racial theory of caste. Several scholars, including Ronald Inden and Nicholas Dirks, have understood colonialism as having ‘created’ caste; this is based on the belief that pre-colonial caste identities were much more fluid than present-day manifestations of it, with caste being only ‘one among many forms of identity’ and having important roles to play in pre-colonial political mobilisation. In other words, the documentation and categorisation of caste is understood to have ‘created’ it.

Scholars such as Sumit Sarkar have argued against this idea, noting that caste was not a colonial creation and was present well before colonialism. The colonial process of caste-documentation was also not entirely a colonial mechanism, and was definitely violently casteist in the sense that the information collection, processing, and writing of the census by the British state was carried out by local high-caste bureaucrats, elites, and pundits. Therefore, while colonialism did create an impact on caste, it certainly did not ‘create’ it. However, the role of colonial governance in caste meant that independent India chose to be wary about the collection of caste information of its citizens. The narrative of the new Indian elite in the 1950s was that old methods were to be scrapped, caste was to be made irrelevant, and a bright new future of socio-economic development was to be heralded by Nehruvian industrialism. Reservations in this context were seen as attempts to compensate for casteism in history, Omvedt notes, and not formulated in order to tackle existing present-day casteism. This then led to the dichotomous and mutually non-exclusive notions of ‘reserved’ and ‘merit’ positions.

Even in the commissions set up to look at issues of caste, specifically with reference to OBCs, failed to provide adequate space to the role of caste- for example, the Mandal Commission used the term ‘backward classes’ to denote a large category of people categorised based on their ‘social and economic backwardness’, an arbitrary distinction that has been argued to be on insufficient data, since it was based on the outdated 1931census. On the whole, this erasure of caste in the public and administrative spheres can be understood as attempts by the elites and upper-castes to brush the issue under the figurative carpet and claim authority, especially since the removal of caste-based censuses have not led to any tangible change in the system. Caste-based crimes remain the norm in society today, as do exclusion and untouchability. Political assertion in many regions is strongly organised on the lines of caste, as seen in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Nadu, the Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and the Samajwadi Party. Caste also continues to have just as much of a role in society as always: the activities of Khap panchayats seem to be growing, and marriages remain on caste-based lines. The removal of the collection of caste data in the census, therefore, has likely made little positive impact on the issue.

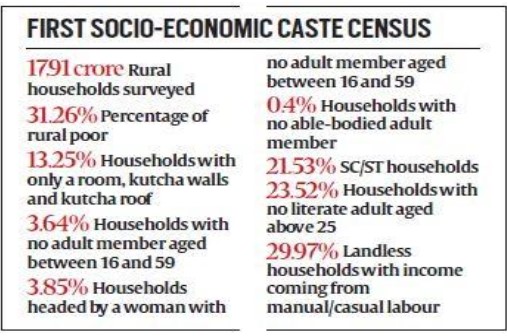

In this context, there have been several arguments for the inclusion of caste information in the census. Firstly, as Sociology professors Satish Deshpande and Nandini Sundar note, caste is a crucial variable in present-day society that defines communities much more significantly than language, religion, or region might. The 1931 survey of castes is detailed, with the population classified into various social and economic categories, and demarcated of various castes and subcastes and a new focus on the enumeration of all the ‘hill and forest tribes’. However, this data has not seen any updating since. Since the census is conducted and collated every ten years, the inclusion of caste in it would allow for periodic revisions of caste data. Second, tracking castes of populations over a long period of time gives us the real picture of socio-economic realities of India and will make the entire practice much more comprehensive and allows for studies of changes in socio-economic positioning of various castes. Census data may help in periodically revising reservation lists, specifically in the OBC category, in order to draw up new lists or add new communities into existing lists based on need and circumstance, and allow for greater inclusion of sub-groups or sub-castes that remain underrepresented even within their reservation categories. A caste census will also allow for more information in general, since caste statistics are severely lacking today. For example, policymakers will be able to understand how resource mobilisation and caste correlate across the nation across a large span of time, or how caste has changed in today’s internet-era, or even how the patterns of inter-caste marriages have spanned out. As there are no government verified numbers available on caste-based population, it becomes extremely difficult to design a roadmap to a progressive change. Hence, inclusion of caste can be a way to rectify this problem.

Currently, as we have seen, India has had no thorough survey on the population and distribution of its castes, and this has significant impacts on government policy decisions. For example, the Justice Rohini Commission was formed in 2017 to look at the equitable redistribution of the 27% OBC quota and has proposed this year to divide all OBC castes into four subcategories that will each get 2%, 6%, 9% and 10% of the total 27% OBC quota respectively, in order to ensure that more marginalised groups do not lose out on their share. But this proposal has come under harsh criticism by the likes of Justice V Eswaraiah , who notes that it is unconstitutional for a commission to place recommendations for OBCs without a thorough investigation. He further says that while the aim is justified, the Rohini Commission has not conducted any nationwide survey of castes before proposing this sub-categorisation, and the implementation of a policy without such crucial demographic information might do more harm than good.

Clearly, there is a strong argument to be made for a caste-census, and with the upcoming 2022 National Census, the calls for a systematic investigation into caste demographics this time seem justified. Such an investigation would have to be fair and thorough, with the intention of ensuring equity and justice to the marginalised, placing more contemporarily appropriate quotas and reservations, and studying demographic change and social trends. In this context, “it is also imperative to note that in any future survey of caste it is not just the Dalits and OBCs whose figures must register in the caste census”. All castes will have to be included, especially that of the upper caste, because in order to better serve the masses, it is essential to better understand the structures and workings of the upper-castes. Omvedt crucially writes that the power of the Brahmins and other upper-castes must be studied in detail: their wealth structures that dominate society, their social control, their authority over institutions, and trends of their growth over time, among others. This must therefore be a central aim of any future caste-census: to study the caste system in order to systematically bring it down.

Sookthi Kav is From Bengaluru, currently a second-year history student at LSR, Delhi University. Loves reading, dance, and classical music. Current Role: Student, writer at Itisaras (Dhaara) ,Ultimate goal: To work in a field where I can learn, explore, and contribute positively to society in some way, and to be happy. Biggest achievement: So far, learning to drive! Educational Qualification: BA (Hons.) History.