Indian theatre with its rich history of presenting narratives that have voiced issues concerning the marginalised caste and communities has, in the past few decades, given way to the feminist issues in the theatrical circle. Even though the theatre in India emerged long ago, it could never give women enough representation in terms of who portrayed their characters; if their issues were recognized and presented in the play and even the fact that the work of women writers and artists was delegitimized for they were recognized as sex workers and singers from the marginalised communities.

Indian feminist theatre, however, has been able to create a space for itself while being appreciated for the way it has presented women’s issues with “bold narratives and progressive representations” as an article by ‘Feminism In India’ states and has come to be recognized as an “intersection of art and activism, and a product of political as well as theatrical movements.”

But how did this theatre form come into being? It was not until the 1970s when the socially relevant narratives that fully recognized and acknowledged women’s issues were popularized among the masses using theatre. Known to have taken origin from an interaction between experimental and theatre movement of the 1960s, the Feminist theatre is as much a political endeavour as it is a theatrical one. As stated in the article ‘Aesthetics of Indian Feminist Theatre’ by Anita Singh “It (feminist theatre) is revisionist in spirit and questions orthodoxy. It questions – phallocentrism: male-centred view of life. Phallogocentrism: male-dominated discourse. It is an avant-garde movement, as it deconstructs and has many facets. It deconstructs patriarchal metaphysics.”

The Indian Feminist Theatre with its belief that the ancient Indian theatre which was dominated by male ideologies in terms of the dramatic text and performances, evolved to share and represent the experiences of women living in a patriarchal society which otherwise would not have been possible in the presence of the sacred traditions of the theatre.

However, the feminist theatre did not limit its working to simply discussing and presenting women’s issues but made sure to encourage more women to enter the theatre circle and work as writers, creators and artists; opportunities which they were denied before. Even as noted in an article by ‘Feminism In India’, “In the next two decades, women’s voices became an integral part of mainstream Indian theatre.” This was made possible through the festivals and workshops organized by theatre groups to achieve the motive of training women actors while celebrating their entry into theatre at the same time.

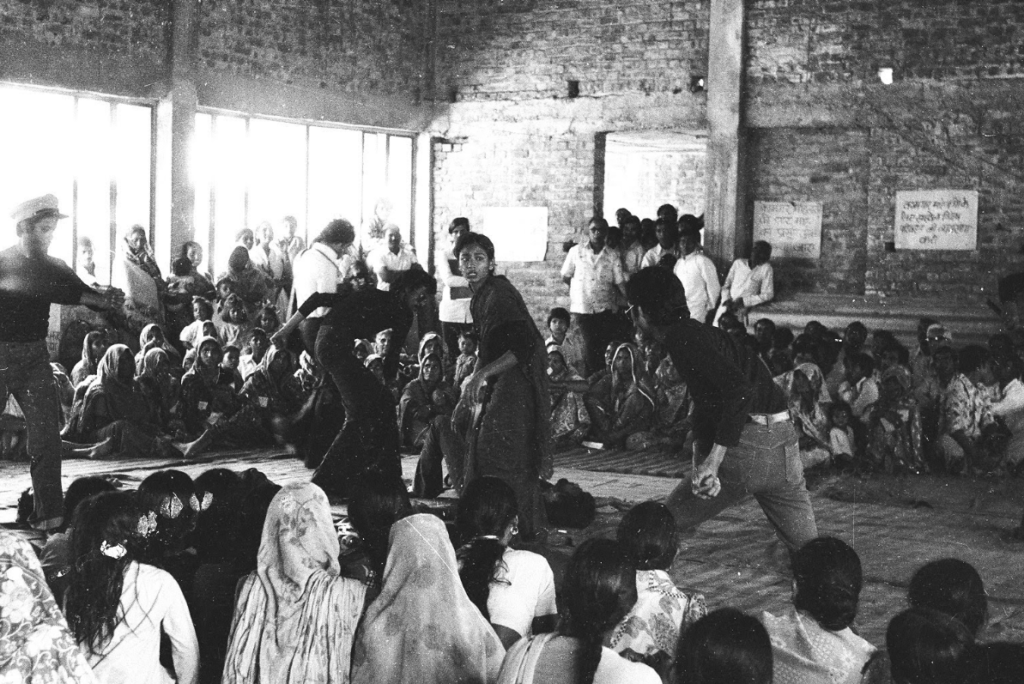

Feminist theatre originally found its audience in non-commercial spaces of the cities and towns in India. Safdar Hashmi’s Jan Natya Manch, for instance, performed an agitprop street play called ‘Aurat’ (Women) in the year 1979 which openly dealt with issues like sati, dowry, and wife battering. The fact that it set out to venture to the public with a diverse ideology talking about the issues women went through – something never presented so publicly, led to the creation of a new audience for the theatre.

Other than this, the Feminist theatre undermined the notions of classical Indian theatre practices that focused on a single protagonist. The plays written by women writers chose to focus on an ensemble thereby dramatizing the feminist belief that a group is more important than the individual. Usha Ganguli’s ‘Antaryatra’, which she both wrote and performed, is the narrative that weaves an autobiographical introspection of the 63-year-old actress/director with the voice of famous women theatrical characters into a rich narrative of feminine consciousness. As explained by Anita Singh, “She attempts to explore Indian women’s psyche through a variety of characters like Nora, Himmat Mai, Rudali, Kamala and Anima.” This play is seen as a tribute to the crucial female heroines who are representatives of real-life women and belong to different social spaces; however, are bound by the virtue of being a woman.

Written in 1974 and performed in 1981 for the first time, Vijay Tendulkar’s Marathi play ‘Mitrachi Goshti’, is one of the first plays in the country that elucidated and presented the theme of homosexuality in women. First performed at Gadkar Rangayatan in Thane, this play was unconventional in itself for presenting the narrative of an unrepentant lesbian, acknowledged as something path-breaking back in the year 1981. The theme of the portrayal of queer women has been carried forward and has begun to crop up in films and stage – a prominent example being Naseeruddin Shah’s staging of Ismat Chughtai’s ‘Lihaaf’.

Other than this, Feminist Theatre’s ideology of putting to fore the argument that identity and gender are dynamic and culturally created and not fixed is reflective in the work of Geetanjali Shree. Umrao (1993), which is the adaptation of Umrao jan Ada, a novel written in Urdu by Mohammad Hadi Ruswa was based on the life of a courtesan. The play aptly questioned the stereotypical image of the courtesan and the woman as a sexual object, embodiment of beauty and glamour, and as a victim.

The last few decades have seen a transformation in the Indian theatre, which can be measured in terms of how it is no longer the male preserve it used to be. Even as acknowledged in an essay ‘The Emergence of the New Woman: Reflections on 21st Century Theatre of India’, “Feminist theatre in India has proved to be a creative theatre that challenges representation of our dominant culture.” Subverting expectations to make possible, the positive and necessary changes in the lives of women politically and theatrically is a goal which is the set point of almost all feminist groups.

Addressing issues like equal pay and equal opportunities, financial and legal independence, equal education, women’s rights to define their sexuality are some set issues that are a part of feminist discourse and are expected to gain light through theatrical representation. As much as the contribution of Feminist theatre has been in achieving the set targets of the feminist discourse, it is difficult to measure the impact it has left on the Indian society for it is only a smaller part of the larger feminist discourse as agreed by an article by ‘Feminism In India’. However, at the same time, it is important to acknowledge how the Feminist theatre has given the women a voice of their own, to empower themselves which in turn puts to view how this theatre form is truly an intersection of art, activism, and social relevance.