Uddhav Thackarey, the Chief Minister of Maharashtra, made a scathing comment when he said, “if the Central Government does not realise that they are harming people for political gains, it will not take much time for States in our country to break away like the Soviet Union. The year 2020 has to be looked at, creating a question mark on the capacity and credibility of the Central government”.

Earlier, centre-state relations were determined by a unique and innovative model that our founding fathers had designed to accommodate the diverse voices of our country. The Shiv Sena’s comments are a reflection of the precarious turn that the nature of our country’s Centre-State relations has acquired in the recent past.

History of the craftsmanship that went into innovating the Indian Federalism

Federal and political theorists have attempted to define the unique nature of federalism adopted by India in different ways. One of the most innovative attempts was by K.C Wheare, who defined India’s polity as ‘quasi-federal’; that is, a “unitary state with subsidiary federal features”. It is interesting to note that the preamble of the Constitution of India denotes the state as a ‘Union’ and not a federation. When Dr. B.R Ambedkar, the president of the Drafting committee of the Indian Constitution, presented the draft constitution to the Constituent Assembly, the word used in Article 1 was ‘Union’, and the word ‘federal’ was never mentioned in the Preamble.

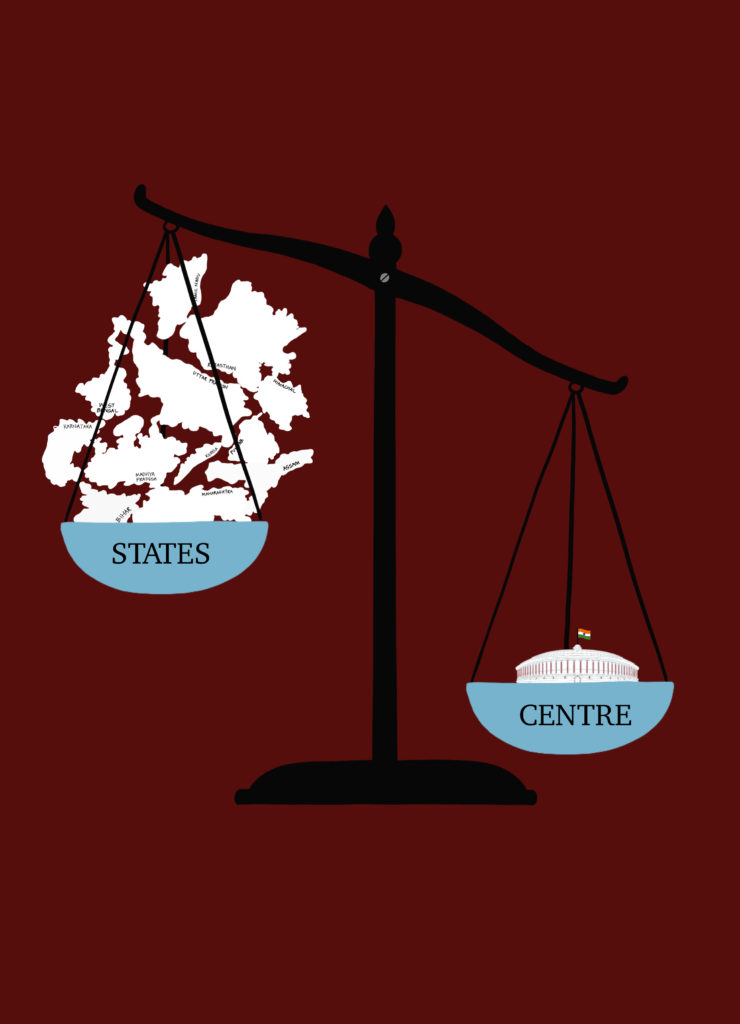

The Constituent Assembly of India took almost three years to craft a unique polity for a nation as diverse, democratic, and large as India. One thing that stands out in our polity is its quasi-federal structure. While a purely unitary system would be one with a very strong centre and states existing only to facilitate administrative logistics and implement centre’s policies, in a purely federal set-up, there are two tiers of government, at the central and state level, both with well-designed functions and powers. This set-up enables the accommodation of diverse voices while establishing the necessary tools to strengthen unity in diversity. The state and central governments both work independently and in coordination with each other to achieve common national goals. In the case of India, the powers of the central and state governments are not equitably divided. The Centre cuts an extra slice from the power-pie and hence has an upper-hand. At the same time, however, India does not follow a unitary system either.

India’s complex polity can be better understood by studying its nature, functions and structure. It would be easier to comprehend the unique and complex nature of India’s customised structure of federal polity by adopting a dynamic perspective in which we differentiate between the constitutional arrangements (theory) and operational realities within the political ethos (practical implementation).

During the making of the Constitution for newly independent India, one of the most fervent advocates of a strong centre was Jawaharlal Nehru, who wrote in a letter addressed to Rajendra Prasad, the President of the Constituent Assembly—the body created to draft the constitution:

“Now that the partition is a settled fact, it would be injurious to the interests of the country to provide for a weak central authority which would be incapable of ensuring peace, of coordinating vital matters of common concern and of speaking for the whole country in the international sphere”.

Nehru’s proposal was met with opposition from several quarters. K. Santhanam, from Madras, eloquently defended the rights of the states. He remarked, “there is almost an obsession that by adding all kinds of power to the centre, we can make it strong…I do not want any constitution in which the Unit has to come to the Centre and say ‘I cannot educate my people. I cannot give sanitation, give me a dole for the improvement of roads, of industries.’ Let us rather wipe out the federal system and let us have a Unitary system”. Santhanam predicted a dark future if the proposed distribution of powers was adopted without further scrutiny. In a few years, he warned, all the provinces would rise in “revolt against the Centre”. One member from Orissa warned that “the Centre is likely to break” since powers had been excessively centralised under the Constitution.

The argument for greater power to the provinces provoked a strong reaction in the Assembly. The need for a strong centre had been underlined on numerous occasions since the Constituent Assembly had begun its sessions. Ambedkar reminded the members of the riots and violence that was ripping the nation apart, and many members had repeatedly stated that the powers of the Centre had to be greatly strengthened to enable it to stop the communal frenzy. Reacting to the demands for giving power to the provinces, Gopalaswami Ayyangar declared that “the Centre should be made as strong as possible”. One member from the United Provinces, Balakrishna Sharma, reasoned at length that only a strong centre could plan for the well-being of the country, mobilise the available economic resources, establish a proper administration, and defend the country against foreign aggression.

Fiscal Federalism

In the light of the aforementioned, in the recent past, our country has seen turbulent changes, which has invited increased attention, scrutiny, and criticism. Political centralisation at the national level came to be upheld with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) coming back to power for the second time in a row in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, with a whopping majority at that. This is testimony to the fact that after a long time India is beginning to witness the emergence of a “dominant political hegemon”.

The same endeavour at the state levels has been faced with opposition and resistance. The rancour at the state level has increased vehemently in the recent years due to the power structure becoming asymmetric in nature. Since 1991 and the commencement of the economic ‘liberalisation’, financial strengths and economic roles of the state governments have been subjected to impairment and subjugation.

The most recent example of this can be seen in the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) by the Centre, which came into effect on 1st July, 2017. The enforcement of the GST implies that that state government’s power to determine the tax rates of the goods produced within their territories is deprived. Additionally, the Centre promised to compensate the states for any loss of revenue incurred for the first five years of the GST regimen.

But due to the downtrend of economic growth, especially because of demonetisation, the Centre was not able to redress the states on its promised compensation. This led to an increased unrest between states and the Centre, especially by the non-BJP led states, like that of Kerala, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Punjab, and Delhi. It is noteworthy that 60% of revenue for these states comes from GST compensation. GST famously and sardonically achieved the name of being the ‘Gabbar Singh Tax’— satirising the basis the antagonist dacoit of the Hindi film Sholay who loots and plunders the villagers. Nonetheless, due to consistent fervid resistance from the state governments, the Centre was compelled to agree to borrow a part of the amount and give the dues to the states.

Haseeb Drabu, former finance minister of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, commented that, “it’s the lowest ebb of the fiscal federal relationship in recent times”. The onset of natural disasters like that of the 2018 and 2019 floods of Kerala, and the Coronavirus pandemic has forced the states to ask the Centre to release more funds, however, to no avail. The decision of the Centre to close liquor shops to check the spread of the pandemic was met with backlash, especially from Punjab who faced severe loss of revenue due to the same. The Centre was coerced to revoke the order.

Law and Order

Independent bodies fostering coordination and to resolve issues, like the Sarkaria (1983) and Punchhi (2007) commissions, were set up to decrease friction between the centre and state governments and also inter-state antagonisms. However, their recommendations were not paid heed to. Thereby, there are no independent institutions who would remedy Centre-state and inter-state issues, which leads to disarray. Punjab Finance Minister, Manpreet Singh Badal, referring to the GST dues, said, “if this is left to the fancy of the central government, there should be a dispute resolution mechanism to ensure that we are able to get what rightfully belongs to us”.

Along the same lines, the issue of internal safety matters concerning the resistance against the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) probing cases within states comes into view. Kerala, West Bengal, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Punjab, Jharkhand, and Mizoram have withdrawn their consent to the central agency probing cases in their states. They have accused the CBI of running a political vendetta and furthering biased opinions.

Former Home Secretary G.K. Pillai says, “[the CBI] has lost its credibility. The onus is on the Centre to take the states along and enhance their confidence in such a central agency”. A permanent council for the same was set up in 1990 following the report on Centre-State relations submitted by the Sarkaria Commission through a Presidential order. However, this council has only met six times in the last three decades, rendering it ineffectual.

The 15th Finance Commission established that the delegation of funds to the various states would be done on the basis of population, following the 2011 Census. This stimulated agitation from the Southern chief ministers accusing the Centre. DMK leader, M.K. Stalin, was of the opinion that this was done without consulting any of the states. According to him, this not only contradicted the principles of federalism but would also help in promoting bias towards certain states at the expense of others.

There was a crash in the price of pepper when the Centre unanimously permitted the import of pepper from Vietnam through Sri Lanka under the South Asia Free Trade Agreement. This particularly affected and perturbed the growers of pepper in Kerala and Karnataka. Many states were forced to reduce the penalties on traffic violations due to public pressure as the fines were increased outrageously when the Centre amended the Motor Vehicles Act.

All of the aforementioned decisions were carried out without taking into perspective the standpoint of the states. An ex-Chief Minister of Karnataka, speaking with reference to the GST Council, had expressed that, “the economic policy that affects India’s commerce with the rest of the world impacts the states, too. Yet, the states have no role in shaping the economic policy. For India to grow stronger, her states need to grow and prosper. We are today in a position to set the states free to grow as per their capacity, without being nervous about any imagined threat from assertion of their identity”.

CAA-NRC

On 19th November, 2019, it was declared in the Rajya Sabha by Home Minister Amit Shah that the National Register of Citizens (NRC) would be implemented throughout the country. Simultaneously, on 11th December, 2019, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act was passed in the Parliament. When the two would be viewed in combination, being a Muslim and without documents would strip one of their citizenship rights. This stirred discontent and mayhem across the country, including state governments publicly voicing their non-cooperation with the same. States and Union Territories alike passed resolutions against the CAA, which included Kerala, Punjab, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Puducherry, Delhi, and Jharkhand. There was resistance from within the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) as well, which further aggravated the situation. Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Telangana, and Maharashtra saw objection in various degrees. There were unprecedented protests across the nation against the central legislation. The constitutional repercussions of the same paved their way to a probable Emergency-like situation. However, the onslaught of the pandemic brought about a forced halt to the unfolding of the consequences of the same.

‘One Nation, One Election’

In November 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a call for ‘One Nation, One election’. The head of the parliament, which has NDA in the majority, argued that this would save public money and reduce the burden on civil functionaries. However, what he did not mention was how easy this would make defecting from political parties and how even minority governments could continue their tenure without public confidence, as they could not be changed before the next integrated election.

If the governments do leave their position, it will ultimately pave the way for President’s rule. Elections to local bodies, state Assemblies and Parliament have their own respective contexts and popular concerns. Mandatory scheduling of simultaneous elections will mean subordinating all elections to the overwhelming central/national context. This would make Indian democracy hollower and the government more centralised than it already is. The Law Commission Report has also proposed that if a no-confidence motion is moved in the Lok Sabha, it must be accompanied by a resolution naming the new leader to run the alternative government. This is termed as a “constructive vote of no confidence”.

National Herald says that according to the proposal by NITI Aayog, situations in which the dissolution of Lok Sabha “cannot be avoided”, the President will take on the reigns of the country and work according to the aide and advice of the Council of Ministers chosen by them. Imposing President’s rule throughout a Parliamentary democracy is reminiscent of the era of the Emergency in the 1970s, characterised by anarchy, abuse of power by extra-constitutional elements, and autocratic rule. These tactics by a political party that has come to realise that it enjoys a disproportionate popularity in the country, are its attempt to concentrate powers in its own hand, and by extension, in the central government.

Farm Laws

Another point of contestation between the Centre and states, which has sparked into the biggest organised protest in human history, is that of the Farm Laws passed by the Centre in September of 2020. In a gist, the farm law claims to help small and marginal farmers to get a better price for their produce and help those who cannot invest in technology to improve the productivity of their farms. The farmers consider that the virtual dismantling of the Mandi system and the minimum support price (MSP) system will deprive them of an assured price for their product.

The Farm Laws were met with opposition from opposition-ruled states. Punjab, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh have passed their own bills in order to counteract and amend the Farm Laws and invalidate them. The Delhi government followed suit as Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal tore copies of the farm laws in a special session. Former Union Minister Y. K. Alagh, who was also a member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, said, “if you bring good legislation like the three farm laws, which are in the concurrent list, through an ordinance and without any discussion with states, they are bound to oppose it”.

While Punjab was a state that did not prominently have any friction with the Centre, in recent years, with the implementation of draconian laws and bills, the relationship between the two has become estranged. Kerala became the fifth state in December of 2020 to unanimously pass a resolution demanding the withdrawal of the farm laws. Alagh is of the opinion that with the manner in which matters are heating up between the Centre and the states, especially the non-BJP ruled states, the governance of the country as a whole would be wounded in an irredeemable manner.

Special Status (Articles 370 and 371)

It is noteworthy that there are some exceptions to the constitutionally mandated federal structure. These special arrangements are incorporated in order to acknowledge and promote diverse identities and improve governance. One of the examples of this exception would be the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, which enjoyed a special status under Article 370 of the constitution. Similar to Article 370 are Article 371 and 371 (A-J), which provide special status to a number of states. This ensures the central government’s laws would not be applicable to them unless passed by their respective State Legislatures.

While Articles 370 and 371 have been a part of the Constitution since January 26, 1950, Articles 371 (A-J) were incorporated through amendments under Article 368, which lays down the power of the Parliament to amend the Constitution and procedure thereof. Article 371 and 371 (A-J), through the various sub-sections, individually address separate provisions for the state of Gujarat and Maharashtra, Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka and Hyderabad. Broadly, these pertain to extending the Governor’s powers or legislative assembly and safeguarding the rights of the tribal communities.

Conclusion

It is ironic that, in recent years, the Centre that has apparently stood by ‘cooperative federalism’, is the one that is predominantly and persistently delving in forms of governance that are eroding the basic federalist structure that our Republic has stood sworn by. Ahead of the assembly polls in Kerala and Bengal, there seems to be friction and skirmishes intra-party, too. 2020, the year that began with CAA-NRC quandary, found itself bound up in the repercussions of the pandemic. The government was highly criticised for the manner in which it reacted to the pandemic. From the Chinese outrage to the so-called “love-jihad” laws to the Hathras rape case, the government will have to traverse a bumpy terrain in the year 2021.

As Alagh rightly says, “there is this whole business of treating the political system in a somewhat cavalier manner. Politics has become very thinly balanced because of all this. It creates instability, which is not good”. It is upon us, the citizens of this nation, to be aware about the intricacies of the proceedings of this nation in terms of knowledge of federal structures, law and order, features of the Constitution, and thereby, keep a check on the steps taken by the government to uphold the democracy that we are. It becomes critical and imminent to join forces in order to bring about a change we wish to be a part of in the subsequent future.

Beautifully carved out. It was a fantastic read. Thankyou for this 🌺