A blend of ritualistic, cultural, and folk expression of the sub-continent and representation of music of different genres, Indian Classical Music as a heritage has evolved through the centuries. Classified into the two categories of North Indian or Hindustani and the South Indian or Carnatic music, this musical tradition is known for its unique blend that has resulted from interactions between people of different races and cultures over a period of several thousand years.

Having roots in religion, folk, and theatrical performance practices, the origins of Indian Classical Music can be found in Samaveda, wherein Sāman means ‘melody’ and Veda means ‘knowledge’. With its own unique theory, notation, instrumentation, and vocal style, it becomes rather interesting to note how this musical tradition has had the capability of blending with other musical cultures. A better understanding can be made by observing how Indian Classical Music, when introduced to Western culture during the colonisation period, gave birth to a hybrid style of music.

The two styles of music, i.e. Indian Classical and Western music, can be differentiated in terms of how they put melody, harmony, and ornamentation to use. Indian Classical Music for instance, considers melody which is derived from ragas as an essential element, whereas Western music considers harmony and counterpoint as the most important elements. So, while Indian music is based on important notes that form a particular raga, Western music bases its compositions on melody and harmonic relativity as discussed by Mounika Parimi in her essay. In fact, the notion that ‘Indian music lacks the concept of harmony’ is what stood out for the British and made them believe that Indian music is unsophisticated and primitive. However, these disparate views were eventually put aside with the cultural and musical exchange between India and Britain that took place in the time when India was a British colony. This gradual development led to the formation of a hybrid musical style that exhibited “stylistic elements from both cultures woven together, resulting in unique and novel sounds” as stated in Parimi’s essay. Thus the next few centuries witnessed some realistic attempts by the then musicians, to develop a novel style of music by successfully bringing the two music styles closer.

Southern India’s Carnatic musician and composer, Muthuswami Dikshitar was one of the first musicians to put this effort into practice. Being raised in a British hub, Dikshitar was exposed to various western music styles which in turn gave him the exposure to other vernacular forms of music. The various western influences that Dikshitar interacted with in his lifetime later became an inspiration for him to compose text for the famous European airs, a request put forward to him by Mr Brown, a British officer stationed in Madras. His idea of composing Sanskrit lyrics and setting these texts to Western airs, to the well-known tunes of “God Save the Queen” and “O Whistle and I will come to You, my Lad”, took off very well and exposed his wide Indian audience to Western music.

A substantially new practice, this gradually exposed both the sides to the new genres of music. While orientalists like Sir William Jones played a key role in making the Western ear more accepting of the Indian musical tradition by employing techniques that substantiated the fact that Indian music employed artistic freedom in the absence or due to the lack of rhythm, contributions made by the musicians of Indian origin also became an essential driving force that brought Indian music on the global platform.

Raja Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore for instance, contributed immensely in helping Indian Classical Music attain a global audience. Having founded the Bengal Music School and Bengal Academy of Music, Tagore went on to form Calcutta’s first ‘orchestra’, for which he also developed hybrid Indian and Western instruments that according to him, played an essential role in unifying and preserving the two musical practices. Owing to his wide acquaintances with leading political and cultural institutions all over the world, Tagore played an important role in increasing the world appreciation of Indian music. His incredible work in terms of preserving and expanding the knowledge of the traditional instruments is something that he is still remembered for.

Yet another example of the same can be seen in terms of how Rabindranath Tagore enabled the creation of a genre which was a true amalgamation of Indian and Western music styles. Drawing inspiration from both Bengali rural folk songs and English folk music, Rabindranath Tagore enabled the possibility of a ‘conscious imitation of Western style but also conservancy of Indian ragas and language, making it appealing to both cultures’ in the words of Parimi.

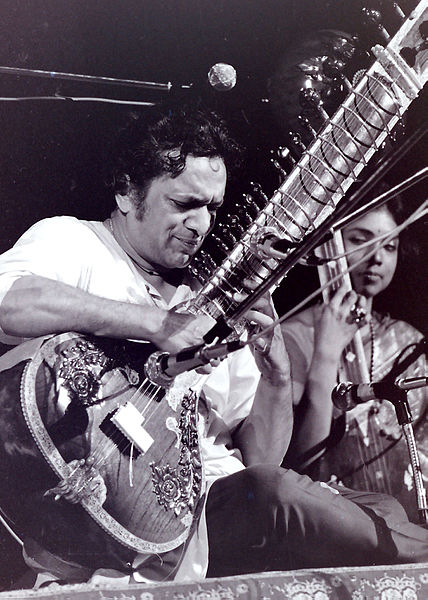

Following the trend set by the musicians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Ravi Shankar also joined the league of musicians who played an important role in popularising the Indian Classical Music in the West. As an article by The New York Times states, “his work with two young semi-apprentices in the 1960s — George Harrison of the Beatles and the composer Philip Glass, a founder of Minimalism — was profoundly influential on both popular and classical music.” It was by means of his recitals and recordings on the Columbia, EMI and World Pacific labels that Ravi Shankar was able to build a Western following for the sitar. In fact, his love for mixing the music of different cultures was evident from the various collaborations he was a part of – for instance the collaboration with the prominent Japanese musicians, Hozan Yamamoto, a Shakuhachi player and Susumu Miyashita, a Koto player.

His far-reaching impact was measured in terms of how the Western listeners who were earlier sensitive to Ravi Shankar’s techniques of expanding on the ragas, later were captivated by the inventiveness employed in the various techniques used by him. To quote Allan Kozinn, “Many sought out the music of other sitar, sarod and tabla soloists, as well as Indian vocalists, and branched out to other forms of world music, from China, Japan, Indonesia and eventually African and Latin American countries.”

These are the innumerable efforts from the past that have enabled new possibilities in the contemporary music world. Global festivals that celebrate this fusion have become a testimony to the journey of Indian Classical Music, which from being contained to a constrained platform has now attained global popularity. A generated interest in this musical tradition remains, but now what becomes important is to ensure what Ravi Shankar believed in, i.e. to convey to the global audience, an awareness of the richness and diversity of our culture as a whole.

We are a gaggle of volunteers and starting a brand new

scheme in our community. Your website offered us with useful information to work on. You’ve performed an impressive task and our entire neighborhood will be grateful to you.