By Debopriya Bhattacharya

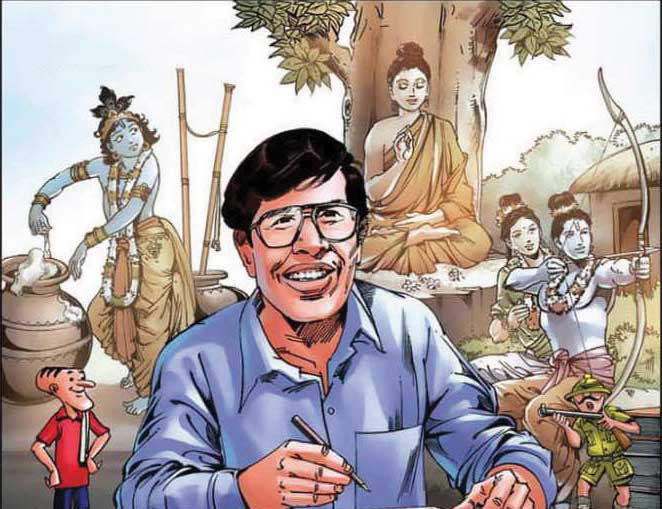

The beginning of the widely read Amar Chitra Katha is often owed to a quiz contest that Anant Pai saw on TV back in the year 1967. On seeing a child failing to answer a question related to India’s history and tradition on the quiz show, Pai deduced that westernisation had resulted in a lack of knowledge of India’s culture, tradition and history among children who were mainly attracted to European comics such as Marvel. Wanting to bring back the lost traditions of India and the struggle of the Indian freedom fighters against the British rule, Anant Pai decided to start a comic book series that would depict the country’s rich heritage of folk tales and mythology through illustrations and child-friendly narratives to make the learning process easier and interesting.

Owing to its colourful depiction of history by means of illustrations, which would otherwise not have gained the interest of the children, Amar Chitra Katha became widely read and, in fact, became a household name in the late 1970s India. Its impact was so much so that it literally became an aid in forming the children’s opinion about the cultural heritage and history of India.

But pertaining to any form of literature, it is well known for how it helps to shape one’s mind about how they see society. It is with this consideration it becomes important to note how the problematic representation of characters in Amar Chitra Katha, in terms of their gender, caste and community needs to be paid heed to.

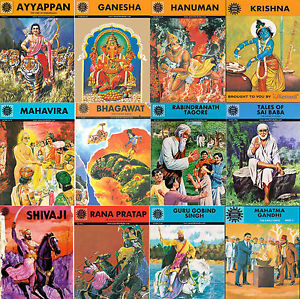

As observed in a study, out of the 400 titles published by Amar Chitra Katha, only 40 books are about female protagonists. Noted by Parveen and Rajesh in their study, ‘Amar Chitra Katha(ACK) Comics in Feminist Perspective’, “ACK women protagonists mostly are the ancient mythological and medieval historical heroines.”

The portrayal of female characters of Amar Chitra Katha is problematised in terms of how women are looked at, i.e. are they looked at as objects of desire or an individual with agency and in terms of how women are portrayed in relation with other characters, especially the male characters.

Titles like ‘Padmini’ and ‘Ranak Devi’ come under scrutiny for venerating sati or women’s suicide ‘as a means to inspire or defy men’, as an article by ‘The Atlantic’ states.

The illustration of heroines like Queen Padmini or Ranak Devi burning themselves alive on the pyre towards the end of their respective stories simply puts forward a rather flawed idea that the figure of the woman is to be seen in relation with a man, i.e. her husband, and that she will devotedly follow him in death too.

Yet another title of Amar Chitra Katha, ‘Kannagi’, based on the central character of the Tamil epic, ‘Silappatikaram’, talks of the chastity and devotion of a woman towards her unfaithful husband. Often quoted in Tamil Nadu to teach chastity and submissiveness to corrupt husbands, Kannagi in Amar Chitra Katha is also shown as a female character with “no individual identity of her own” as quoted in Amar Chitra Katha Comics in Feminist Perspective. It furthermore illustrates that “ACK’s Kannagi presents Kannagi as a ‘chaste wife’ of Kovalan who attains ‘goddess status’ as a gift for her chastity.”

Besides, inaccurate representation of Madhavi, a character from the above-mentioned Tamil epic, as a woman devoid of her agency and voice to explain her thoughts unlike her character in the epic, further brings to fore the problematic idea of restrained agency for women.

Furthermore, Amar Chitra Katha is also often criticized for being the carrier of caste-based colourism. By means of illustrations and skin colour, it subtly reinforces the notions that categorise characters as rich, poor, ugly, beautiful, weak or powerful.

The practice of showing heroic, rich or characters from upper caste in light colours and characters with demonic qualities and those from a lower caste in dark colours, has only furthered the divide in the way people belonging to these communities would be looked at in real life and has only “forwarded the ideology of colourism to the present and the future generation.”

Illustrations in ACK titles such as ‘Ananda Math’ and ‘Devi Chaudhrani’ are some examples of portrayal of caste-based colourism in the comic.

To simply quote from Parameswaran’s ‘Melanin on the margins: Advertising and the cultural politics of fair/light/white beauty in India’, “The practice of conjoining light skin to upper caste status, powerful and wealthy men from the Zamindar community, a feudal and land-owning upper caste, is coloured in pink in the comic books “Anand Math” and “Devi Chaudhrani.”

It becomes easy to make a point about how the skin colour of the characters becomes a determinant of their position and how they will be looked at in the society as discussed in an essay that analyses in depth, children’s perception of Amar Chitra Katha’s ‘Ananda Math’ and ‘Devi Chaudhrani’. It elaborates on how the impact of reading a comic that uses this technique often affects the way the children perceive the characters in the comic and how they come to relate themselves with the characters.

In light of the various criticisms Amar Chitra Katha has been subjected to, the executive director of ACK media, Reena Puri has clarified in an interview that a decision has been taken to hold back inappropriate stories with certain other changes being made keeping in regard the ‘sensibilities of the age’.

But, it becomes important to remember that for a book having attained the popularity of being read by children worldwide, ACK carries the responsibility of depiction of history in a way, such that it’s not only interesting to read but also ensures that any prejudice that may arise due to problematic illustrations is omitted.