By Debopriya Bhattacharya

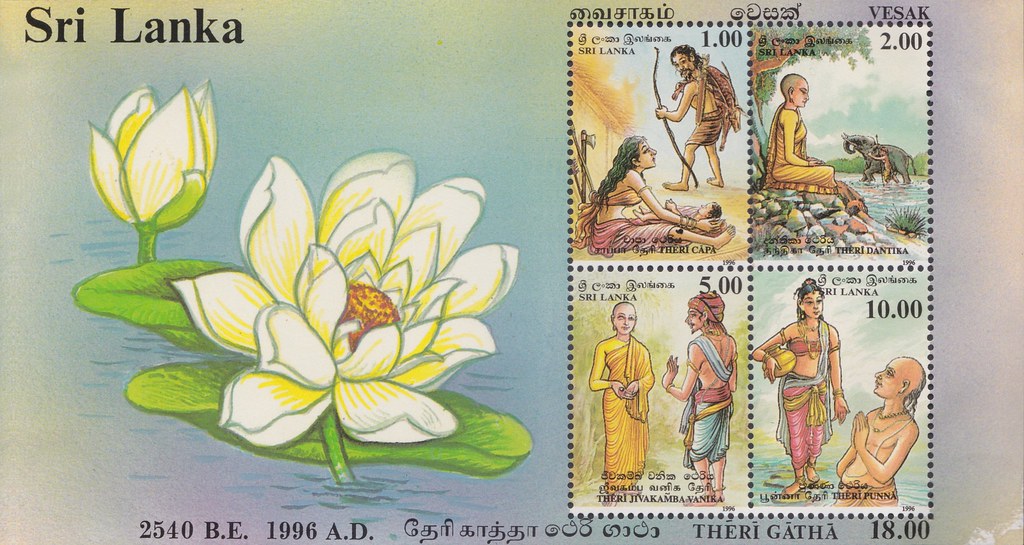

Understood as an anthology by and about the first Buddhist women, Therigatha is also known to be the collection of some of the first poems by women in India. Formed by the two words, theri (elder Buddhist nuns) and Agatha (poems), the word Therigatha literally translates to ‘Verses of the Elder Nuns’.

Finding their origin in as late as the third century B.C.E., this collection of poetry has been received in the Pali language, the scholarly and religious language unique to the Theravadin Buddhist traditions. However, it is considered that the first Buddhist poems were written in a number of ancient Indian vernacular languages and then translated into the Pali language and reworked as the language evolved. Forming a key part of the Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, this collection of poetry is known to have been written till the sixth century C.E.

Based on ideas about the nature of the world, as shared by early Buddhism with other Indian religions, Therigatha is known to have 73 poems that have been organized into 16 chapters.

But who were these elder Buddhist nuns who wrote this poetry?

Theris were essentially the early female followers of the Buddha who have been identified to have converted to Buddhism due to an interplay of forces of two kinds. To quote Arvind Sharma, “a theri could either be drawn towards Buddhism by what she found compelling in it or she could be moved towards it by forces operating within her personal and social situation.”

Therigatha is known to contain stories from the lives of these nuns, recorded in the form of verses while assuming the “standard Buddhist description of a person in impersonal terms, “the dhamma about what makes a person” as stated in an essay ‘Poems of the first Buddhist Women”.

To look deep into why these verses hold significance can be explained by the fact that these are the inspired utterances of enlightened women. But at the same time, it makes it important for us to discuss how these enlightened women and their verses have been looked down upon or problematised in their companion text, Theragatha, understood as the verses of elder Buddhist monks.

Since both these forms of poetry deal with the idea of transience of the physical body, an interesting observation can be made in terms of how the methods to achieve liberation are understood and employed in each of these collections in a different manner. As stated in a research that discusses the comparative analysis between Therigatha and Theragatha, “The liberation for the theris, comes by observing their own bodies and through their own experiences. The theras, on the other hand, achieve liberation by perceiving another, i.e. the desirous woman and recalling to mind the images of putrefaction and decay of decomposing corpses so as to establish ‘disgust with the world’.

It thus becomes a point to note how the Theragatha is comfortable in its position of denouncing women fervently when in reality both men and women are spiritually equal.

Another interesting point to note is that these vividly detailed poems carry the stories of the nuns, free of self-pity and blame, or as how George-Therese Dickenson states, they (elder Buddhist nuns) “turn their tragedies into steps toward spiritual understanding and freedom”.

But then why is something written twenty-five hundred years ago relevant now? Sarah Clelland in her review of ‘Therigatha: Poems of the First Buddhist Women’ says that “among the current discussions about bhikkhuni ordination and the continued marginalisation of women in some traditions, these verses speak to us across the centuries.”

Therigatha is known to be one of the few Pali works which have entered the canons of modern world literature in various translations as noted in a research article. The reason for the same can be attributed to the attention given to the social realities of women in the poems. While speaking of growing old, depression, motherhood, childlessness, menopause, these poems at the same time reject materialism and celebrate friendship and intimacy.

For instance, there are poems that speak of friendships that endure transition between lay life and ordained life and the enduring relationships between female teachers and female students, as noted by the various scholars.

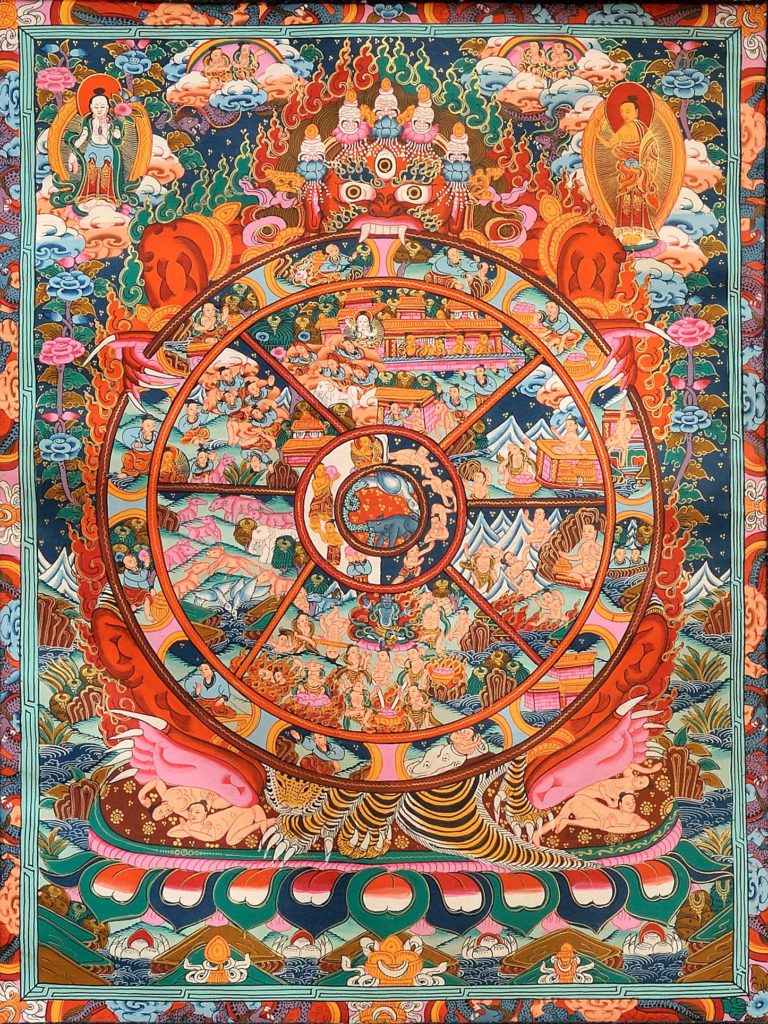

The verses of Therigatha reflect the praises of the four noble truths as sung by the theris:

a) dukkha (suffering) b) tanha (cause of suffering or craving) c) nibbana (cessation of

suffering) d) ashtangika marg (eight-fold path leading to nibbana)

Besides, Therigatha can also be seen as records of the societal perspectives of the gender

differences i.e. these verses don’t acknowledge the basis of gender difference; an idea that

can be explained by the following verse (Soma in conversation with Mara— the evil one):

Soma: What harm is it

to be a woman

when the mind is concentrated

and the insight is clear?

("If I asked myself:

'Am I a woman

or a man in this?'

Then I would be speaking Mara's language.")

(Norman 1991: 158-159)

Considered as a brilliant record of essential womanhood in the Therigatha, this verse can be understood in terms of Soma’s dialogue where she questions, “Am I a woman in these matters, or am I man, or what not am I then?” which is tantamount to coming under Mara’s sway, as a research article on the same discusses. “Self-purification must be the goal for all irrespective of their sex” as stated in the essay ‘Voices from the Yore- Therigatha Writings of the Bikkunis’, makes it rather clear about how the path to nibbana or salvation can be pursued without worrying about the injustices women might have to face, owing to their gender.

It thus won’t be wrong to say that Therigatha, with its poetry resplendent with images of ‘immense beauty’ and ‘horrifying decay’, has had the ability to speak to us about ourselves and our world, making us see it in more insightful ways, a reason why it continues to resonate with the readers of the 21 st century.