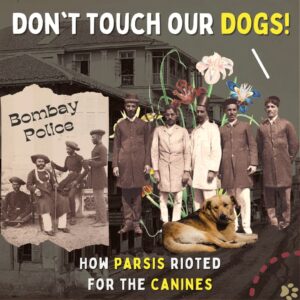

In the bustling tapestry of Bombay, where every corner holds a story, a tale unfolded that echoed with the fervor of protest, the chaos of disturbance, and the strain of bittering relations—all in the name of ‘man’s best friend.’ Wandering freely through the streets were canines, a ubiquitous presence that stirred both concern and disdain. Viewed through the lens of colonial powers in India, these feral dogs were symbols of a primitive culture, a perceived threat to safety and hygiene.

In the bustling tapestry of Bombay, where every corner holds a story, a tale unfolded that echoed with the fervor of protest, the chaos of disturbance, and the strain of bittering relations—all in the name of ‘man’s best friend.’ Wandering freely through the streets were canines, a ubiquitous presence that stirred both concern and disdain. Viewed through the lens of colonial powers in India, these feral dogs were symbols of a primitive culture, a perceived threat to safety and hygiene.

In the scorching heat of Bombay’s summer, these creatures were painted as wild and vicious, blamed for the spread of rabies. If the officially sanctioned annual culling of ownerless dogs during the hot months wasn’t sufficiently draconian, the Magistrates of Police in Bombay sought the nod from British authority to reinvigorate this regulation in May 1832. The solution proposed to curb the pariah dog conundrum was an extension of the annual cull, sweetened by a reward of eight annas for each dispatched dog. The lucrativeness of this new regulation did not elude the opportunistic eyes of the populace and people started capturing and killing dogs, most of which were neither stray nor dangerous, but rather stolen from private enclosures. Excessiveness on the part of these bounty hunters was blamed on the negligence and carelessness of the government.

In the eighth century CE, a wave of Zoroastrian refugees, known as Parsis, journeyed from Iran to India, and over time, this community evolved into a unique ethnic and religious minority, finding its home in the vibrant landscapes of Gujarat and Bombay. As the colonial winds of change swept through India, the Parsis skillfully navigated these currents, weaving intricate ties with the British that proved to be a boon economically, socially, and politically. They rose and gradually dominated Bombay’s commercial space, controlling an extensive commercial enterprise which ranged from the procurement and distribution of goods to the operation of local and overseas trade, with their own ships. The summer of 1832 bore witness to a rift in the harmonious relationship. A seemingly unrelated event, the annual wholesale slaughter of dogs, became the reason for discord.

Dogs hold a sacred place in Zoroastrian belief and the performance of obsequies, serving as guardians of the Bridge of Judgment in the afterlife, and the companion of the righteous across the Bridge to Paradise. A key Parsi funerary rite, sagdid, involves presenting the deceased before a dog to confirm death. For the Parsis, in particular, the destruction of the dogs lacerated religious sensibilities. The first signs of unrest appeared on June 6, 1832, a holy day for the Parsis, as the police initiated the dog cull in Bombay’s Fort area. Home to a large Parsi population, they were outraged by the violation of their religious sentiments, and confronted the authorities, resulting in the assault on two European constables on patrol, who were not even engaged in the killing of dogs. This marked the Parsis’ first act of defiance against British authority. Chaos and pandemonium swiftly took hold, prompting the closure of all shops and public establishments. Within an hour or two, a “disorderly rabble principally composed of the lower classes of Parsees”, congregated before the police office and Supreme Court in the Fort. Their collective demand resonated through the air: an immediate halt to the dog cull. After lingering for a while, the crowd dispersed peacefully. By early evening, a symbolic protest unfolded with shops once again shuttering, enveloped in an atmosphere of defiance and intimidation.

Dogs hold a sacred place in Zoroastrian belief and the performance of obsequies, serving as guardians of the Bridge of Judgment in the afterlife, and the companion of the righteous across the Bridge to Paradise. A key Parsi funerary rite, sagdid, involves presenting the deceased before a dog to confirm death. For the Parsis, in particular, the destruction of the dogs lacerated religious sensibilities. The first signs of unrest appeared on June 6, 1832, a holy day for the Parsis, as the police initiated the dog cull in Bombay’s Fort area. Home to a large Parsi population, they were outraged by the violation of their religious sentiments, and confronted the authorities, resulting in the assault on two European constables on patrol, who were not even engaged in the killing of dogs. This marked the Parsis’ first act of defiance against British authority. Chaos and pandemonium swiftly took hold, prompting the closure of all shops and public establishments. Within an hour or two, a “disorderly rabble principally composed of the lower classes of Parsees”, congregated before the police office and Supreme Court in the Fort. Their collective demand resonated through the air: an immediate halt to the dog cull. After lingering for a while, the crowd dispersed peacefully. By early evening, a symbolic protest unfolded with shops once again shuttering, enveloped in an atmosphere of defiance and intimidation.

The Parsi outcry against the slaughter of dogs reverberated far beyond the confines of their religious community and everybody lent their voices to the protest, showcasing a unity born out of a collective resistance against the encroachment of colonialism upon the sacred tapestry of Indian religious customs. As the dawn of June 7 unfolded, the wheels were set in motion for a full-scale commercial strike and cessation of daily activities, strategically designed for the inconvenience of residents throughout Bombay Town and Island, especially the British. Bazaar shops shuttered, workers supplying provisions to the British garrison at Colaba, and troops on ships in the harbour faced disruptions and harassment. Streets saw water carriers with overturned carts, as organized groups ensured the strict observance of the day’s strike. The British, heavily reliant on Indians for daily sustenance and routine, were visibly distressed by the unfolding situation. The Fort became off-limits as crowds of Indians restricted access. By 11 a.m., a large crowd of Indians, numbering up to 500 individuals, gathered in front of the Fort Central police office. As the clock struck noon, a unit of His Majesty’s “Queen’s Royals” descended upon the scene to assist the Senior Magistrate of Police. The crowd was sternly urged to disperse. Undeterred by the cautionary words, the Senior Magistrate recited the Riot Act, after which the military swiftly took charge, dispersing the crowd and detaining the instigators. People fled from the site, and later the crowd did not assemble again.

Despite the chaotic events, the toll on human life was surprisingly minimal, with only two soldiers succumbing to the relentless heat. Yet, the unfolding saga on June 6 and 7, 1832, left an indelible mark on the British psyche.

Despite the chaotic events, the toll on human life was surprisingly minimal, with only two soldiers succumbing to the relentless heat. Yet, the unfolding saga on June 6 and 7, 1832, left an indelible mark on the British psyche.

The British authorities, gripped by a sense of apprehension, wasted no time in launching thorough investigations. The confluence of the strike and ensuing riot fueled suspicions among the British, fostering a belief that this was not merely a spontaneous outburst in response to the controversial dog slaughter but rather a meticulously orchestrated conspiracy. Fingers were pointed at Parsi leaders and they were accused of disgraceful and disloyal conduct. However, these leaders could not be punished without evidence of their participation, particularly when they had no legal obligation to maintain order among the Parsis. A section of British authority grew increasingly critical of the intricate sociopolitical dynamics unfolding in Bombay between the British and the local Indian populace. The comparatively amiable atmosphere of freedom and racial harmony in Bombay, in stark contrast to the situations in Calcutta and Madras, was perceived as a factor exacerbating the erosion of societal order.

The strike and riot laid bare the facade of loyalty among Indians and highlighted the feebleness and ineffectiveness of the Indigenous leadership in the face of such turmoil. Throughout the strike and subsequent riot, the influential heads of the Parsi Punchayet and prominent shetias in Bombay found themselves largely sidelined. In the aftermath of the riot, Parsi and Hindu leaders urged people to provide information surrounding the strike and riot, and simultaneously, mandated all businesses to remain operational with no further disruptions. This collective effort aimed at cooperation with British authorities reflected a strategic move by the leaders to not only restore order in Bombay but also to reclaim their authority and reputation. In a diplomatic manoeuvre, forty prominent shetia leaders petitioned for the humane relocation of ownerless pariah dogs to a suitable location under their supervision, opposing their outright extermination. This seemingly humble plea, however, was a nuanced propaganda document crafted to reassure the British of the enduring loyalty of these Indian leaders. The British welcomed the cooperation, given this was at their own expense.

In their assessment of the situation in the weeks following the strike, the British reluctantly had to accept the religious and contextual factors that contributed to the ill-conceived and seemingly spontaneous upheaval in Bombay. By October 1832, nineteen individuals, featuring ten Parsis, faced trial. Pursuing these accused orchestrators had been a governmental priority, as evident in the reward for their capture. The verdicts revealed ten individuals, five of them Parsis, guilty of various charges, including conspiracy, assault on police, and rioting, but no evidence substantiated any “political” motive aimed at coercing or compelling the government.

In their assessment of the situation in the weeks following the strike, the British reluctantly had to accept the religious and contextual factors that contributed to the ill-conceived and seemingly spontaneous upheaval in Bombay. By October 1832, nineteen individuals, featuring ten Parsis, faced trial. Pursuing these accused orchestrators had been a governmental priority, as evident in the reward for their capture. The verdicts revealed ten individuals, five of them Parsis, guilty of various charges, including conspiracy, assault on police, and rioting, but no evidence substantiated any “political” motive aimed at coercing or compelling the government.

The practical imperative of curbing the menacing dog nuisance and a desire to avoid appearing influenced by recent events led the British to consider the continuance of the cull. The financial commitment to this effort was substantial, with an annual expenditure of around 3,200 rupees for Bombay Town and Island, accumulating to a total of 31,390 rupees between 1823 and 1832, resulting in the demise of over 63,000 dogs.

The June 1832 events dealt a blow to the Parsi reputation, casting a shadow on the relationship with the British. The notorious Dog Riot of Bombay left a lasting mark, momentarily straining the bond between the communities. However, in the aftermath, it triggered a reevaluation of colonial perspectives on age-old customs. The disruption caused by the strike and riot induced shock, dismay, and an undercurrent of paranoia within British colonial circles. Yet, this tumultuous episode ultimately paved the way for a more enlightened and tolerant comprehension of how traditional society reacts when its customs are interfered with.