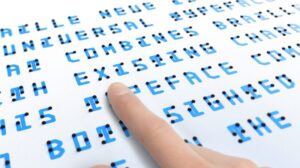

Braille, a system of raised dots representing letters, numbers, and punctuation, has long been associated primarily with aiding the blind in reading and writing. However, this tactile script is far more than a tool for the visually impaired; it is a dynamic, multilingual script with a rich history of evolution and adaptation. At its core, Braille consists of six dots arranged in specific patterns, forming characters that can be read by touch. Each character represents a letter, number, or punctuation mark, allowing for the transcription of various languages. Unlike traditional written scripts, Braille is not confined to a single linguistic structure. Instead, different languages utilise unique arrangements of dots to represent their respective alphabet, ensuring accessibility for speakers of diverse languages.

Braille, a system of raised dots representing letters, numbers, and punctuation, has long been associated primarily with aiding the blind in reading and writing. However, this tactile script is far more than a tool for the visually impaired; it is a dynamic, multilingual script with a rich history of evolution and adaptation. At its core, Braille consists of six dots arranged in specific patterns, forming characters that can be read by touch. Each character represents a letter, number, or punctuation mark, allowing for the transcription of various languages. Unlike traditional written scripts, Braille is not confined to a single linguistic structure. Instead, different languages utilise unique arrangements of dots to represent their respective alphabet, ensuring accessibility for speakers of diverse languages.

One of the remarkable aspects of Braille is its continuous evolution over time. As it requires significant effort to transcribe, innovations have emerged to streamline the process and improve readability. One such innovation is the development of contractions, where multiple letters or words are represented by a single or less number of Braille characters. For example, the contraction “c” can signify the word “can” and “abv” can represent the word “above”. These contractions reduce the length of Braille texts and enhance efficiency in reading and writing. However, the introduction of contractions had its own limitations particularly in distinguishing between contracted and uncontracted letters. To address this issue, additional dots have been incorporated into the Braille system. By adding dots, 5 and 6 before a character, readers can differentiate between contracted and uncontracted forms. This implies that dots 5 and 6 plus c represent c whereas c without dots 5 and 6 would mean can. This refinement ensures precision in interpreting the braille text written.

Another significant advancement in Braille is its adaptation for mathematical notation. In 1952, mathematician Dr. Abraham Nemeth developed the Nemeth Code, a system of Braille symbols specifically designed for mathematical expressions. Over time, the Nemeth Code has undergone revisions and refinements, allowing for the representation of complex mathematical concepts in Braille format. However, challenges persist in creating a comprehensive Braille code for mathematics that is both efficient and space-saving.

To address these challenges, researchers have explored the potential of expanding Braille to include additional dots. The introduction of eight-dot Braille increases the number of possible arrangements, offering greater flexibility in representing mathematical symbols and expressions. This innovation represents a crucial step forward in enhancing the accessibility of mathematical content for individuals who rely on Braille.

In addition to advances in Braille transcription, there have been important developments in the methods of inscription. Traditionally, Braille was embossed using a stylus on paper placed in a slate with indentations for the dots. While this method served its purpose, it was labor-intensive and time-consuming. To overcome these limitations, various technologies have been developed, including braille printers and Electronic Braille Displays. Electronic Braille Displays represent a particularly groundbreaking advancement, offering real-time translation of digital text into Braille format. These devices allow individuals to access written content in Braille without the need for printed materials, significantly enhancing independence and accessibility. Moreover, electronic Braille displays have the potential to facilitate communication between individuals with and without visual impairments, bridging the gap between the two communities.

Despite its significance as a tool for the visually impaired, Braille’s origins lie in a different context altogether. Louis Braille, the inventor of the Braille system, drew inspiration from a military communication method used at night. This historical connection underscores the broader potential of Braille beyond its association with blindness. By introducing Braille education to a wider audience, we can equip individuals with valuable skills and foster inclusivity in communication.

Moreover, promoting Braille literacy among sighted individuals can help distribute the cognitive load of reading and writing more evenly across different sensory modalities. Rather than relying solely on visual input, individuals can leverage tactile and auditory cues to process information, reducing strain on the eyes and promoting overall cognitive health.

In conclusion, Braille is far more than a script for the blind; it is a versatile and adaptable system with the potential to enhance accessibility, facilitate communication, and promote cognitive diversity. Through continuous innovation and education, we can unlock the full potential of Braille and ensure that it remains a vital tool not only for individuals with visual impairments but for the entire community.