The practice of prognosis in the psyche of Indian consciousness is a rich complex one. Localized cults and mainstream religious institutions have thus devised some of the most unique directives for this apprehension for the future in providing divine explanations in deciding an individual’s fate in the universe and his enactment of actions implicating his spiritual and future selves. In the exploration of this phenomenon in the context of certain historical backgrounds and social behaviourism among the localized cults, the significance of Satwai, a folk goddess in the Deccan region, emerges as a dominant enigma for the understanding of this progression.

The practice of prognosis in the psyche of Indian consciousness is a rich complex one. Localized cults and mainstream religious institutions have thus devised some of the most unique directives for this apprehension for the future in providing divine explanations in deciding an individual’s fate in the universe and his enactment of actions implicating his spiritual and future selves. In the exploration of this phenomenon in the context of certain historical backgrounds and social behaviourism among the localized cults, the significance of Satwai, a folk goddess in the Deccan region, emerges as a dominant enigma for the understanding of this progression.

The cult of Satwai, as per the research carried out by anthropologists, is steeped in a hoary history with no precise trace of its occult practices. However, few scholars, such as DD Kosambi, have conjectured the genesis of this cult in a general sense as a prerogative of a defunct or absorbed tribal cult. This attitude is supplemented by the establishment of shrines in an exclusively local area and the worship of the shapeless forms of stones as the early idols of Satwai.

Reliance on local knowledge has equated her to a dangerous and malevolent mother goddess. A recurring phenomenon is observed in other localized deities. Emerging from a local cult doesn’t mean that she is not mentioned in the mainstream Brahmanical literature, but on the contrary, references are made to her association with Skanda (also known as Kārttikeya), who in devī bhāgavatapurāṇam is called a sasthi priya or a husband of Sasthi (an epithet of Satwai). However, she still emerges as an unmarried goddess in most of her depictions, appearing in accompaniment to Mhasoba (an ancestral buffalo deity). According to her etymology, the word ‘Satwai’ comes from the Sanskrit expression ‘Sasthi’, to mean ‘sixth’, a proposition to the ritual held on the sixth day of the child’s birth.

In the local populace, she is known as a Vidhidevta, or goddess of fate or destiny, who has the power to either shorten or prolong the life of a newborn child. Local women, therefore, often light a lamp, which is left burning for an entire night and the following day, marking the beginning of the propitiation ritual. Accompanied by the midwife, the mother with her child in the darkest room of the house remains as ever watchful of her offspring, stemming from the belief that if the mother so desires to sleep, then her child will be abducted by the goddess herself. Singing of songs and narrating the legends of Satwai are expressed by the family members along with the neighbours, who equally participate in this ritual.

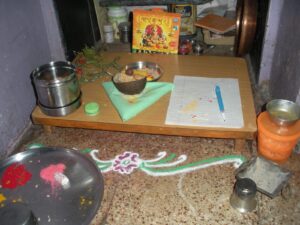

Only in its conduction is the nature of Satwai as the goddess of destiny revealed, from the offerings made of a common saddle quern with muller stone and writing materials to a small shrine erected in the corner of the house. The worshippers believe that the goddess, manifesting herself in someone, might come in person at night and write the destiny and character of the child either on the forehead or on paper for others to read. This activity of the goddess’s prediction is known to the high-caste Brahmins as Brahma-likhita. At the juncture of the ritual, fresh coconut chips and boiled grains are distributed among the guests. The whole idea of these practices reveals how the nature of fertility and the continuance of the survival of their child were important factors that led to the building of such practices to mentally assure the child’s health in the age of transient existence of the newborn.

Originally, her cult was centered in the Latur district of Marathwada, but with widespread acceptance, it extended to other regional centres with variants in calling of the goddess from Vidhiamman in South India, Satvai in Goa, and Setvi tayi in Northern Karnataka, providing rich and lurid narrative accounts of popular divine instances. A common property that cohabits the worshipping pattern of each of the religious centres of Satwai is that on the sixth day of the lunar month, a major ritualistic prayer is upheld to propitiate the reigning goddess.

Bypassing the traditional values surrounding the cult, the changing times have cumulatively influenced the nature of her worship, leading to the dilution of certain rituals, iconography, and the landscape of her shrine. A prime example of this could be foreseen in the Satwai Temple of Dubere village, in which the inceptive shrine of mud and stones is transformed into a standardized and regulated brick-walled structure. The celebrated figure of Satwai is also replaced, from a shapeless simple stone to her depiction in her inherent nature of writing fate on the forehead of the child in sculpted stone. Ritual practices have also received a setback in that the more personal tradition of organizing a ritual has been done away with in favour of a simplistic offering of just the hair of a newborn child by the parents, thus deviating from the more complex and primitive roots of her worship.

It is therefore not surprising to observe that with the transformation of Satwai’s cultic practices, the attribution has also been affected, in which an inclination of her representation as the goddess of fertility is forwarded in recognition of modern worries, thus changing the whole dynamism of the deity. The advent of a modernised state with its stress on education and healthcare has also impeded the worship of Satwai, limiting her worshippers to a substantial level. However, even in the age of transformation, a peculiar fact persists. The preeminence of Satwai, who still oversees her devotees without any structural bindness to hegemonic male patriarchy, as incurred from the delegation of goddesses as just another consort to the male gods, diverts from an established stance, which reveals the nature of the food-gathering or tribal lifestyle of the primitive society to which the cult of Satwai could be readily attested.