The Pahari region has always been a fascinating topic for geologists, anthropologists, and historians due to the sheer complexity and dynamism it exhibits in its topography, culture, heritage, and art. Scenes of lovemaking and mysticism against picturesque landscapes are central to their paintings. As noted by S. Kossak, “unlike the Mughal painting which is primarily secular, the art of painting in central India, Rajasthan and Pahari region is deeply rooted in the Indian traditions, taking inspiration from Indian epics… the Puranas, love poems …folklore… Vaishnavism, Saivism, and Sakti.”Therefore, Pahari paintings are a distinctive school in their own right.

Moreover, these paintings aren’t easily categorised like your Mughal paintings, solely defined by the imperial patroniser due to the prevalence of local culture and the simultaneous migration of painters. To understand this, one must look into the earliest Pahari works, i.e. the Basohli Paintings that underwent gradual assimilation while still keeping the Pahari essence intact.

Basohli is located on the river Ravi in Jammu and Kashmir. It was one of the 36 states ruled by a separate Raja. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Basohli was one of the prosperous regions due to its inclusion in trade routes passing through places like Nahan, Guler, and Nurpur to Jammu. Moreover, 700 families of Kashmir pashmina weavers had settled their businesses. While various scholars see Raja Kirpal Pal’s patronage as the cause of the emergence of Basohli paintings, the presence of decorative elements, mature expression, and bold colours emphasise that the style in professionalise ateliers would have been prevalent before Kripal’s reign.

M.S. Randhawa argues that in the case of artists, the earliest migration from Delhi to the Hill States was undertaken under the patronage of Raja Sangram Pal which gave rise to Basohli paintings. He was friends with Dara Shikoh and was considered a “royal favourite” in the courts of Shah Jahan. Emperor Aurangzeb’s disapproval of such fields further gave impetus to artists who were in search of both “security and freedom”. Thus, it is under him that the Punjab Hills workshop drove away from Mughal influences by revolving around indigenous Rajput tradition, especially in the use of their bold primary colours, themes, and patterns.Moreover, part of the reason for choosing religious themes was against the backdrop of the rising importance of vernaculars, especially with the growing prevalence of Vaishnavism.

In the painting The Worship of The Devi as The Dark Goddess Bhadrakali (1660-70) one sees Bhadrakali (centre) standing against the monochrome yellow backdrop with red borders and a narrow sky, fundamentals of Basohli paintings. She wears extensive three-dimensional detailed ornaments and a transparent dupatta. Interestingly one can see the halo behind her that symbolises divinity. Her gaze is piercing toward the three figures of goddess Kali. They are holding bloodied swords, heads, and blood-filled cups as an offering. Like Bhadrakali, they are ornamented with pearls and animal skin. Behind her is Bhima with Vahni-Priya and in front, two figures of Shiva kneeling and giving their offerings. The Sanskrit text imprinted behind the canvas describes Bhadrakali as “equal to a thousand rays of the rising sun”.

By the 16th century, Krishna worship would also become popular due to the works of Sur Das, Mira Bai, and Bihari Lal. Mysticism would become synonymous with love and sensualism. According to historian Randhawa the image of Krishna as a cowherd against “shady bowers, grassy swords, murmuring streams, exquisite viands, and lovely women ” would gain prominence within the hills.

Another example is Rasamanjari written by Bhanudutta. It is a treatise on rasa that deals with Nayaka-Nayika (heroes-heroines). In the 1690s Raja Kirpal Pal commissioned Devidasa to create an elaborate series of Early Basohli paintings. One of the paintings, Shiva and Parvati Playing Chaupar (1694-95) showcases this relation. Against red borders and mustard background, we find Shiva has just cheated Parvati of her necklace during a game of chaupar. Both of them are sitting on the tiger skin with Shiva’s body facing towards the viewer while his eyes glance over Parvati who seems resolute in gaining her necklace back.

Though a lot simpler in its composition, the application of bold colours, lotus-like eyes, receding forehead, and high nose define Basohli paintings. The presence and stylisation of trees are other significant aspects of the Basohli style.

Interestingly we also find portraits of Raja Kirpal Pal dating to the 1690s. Many were painted with subjects like servants, consorts, and concubines, therefore, depicting the social order. Interestingly, one would observe other Mughal influences in the form of women’s transparent drapery and Kirpal Pal’s jama though the facial design showcases local variation.

The Basohli style’s ferocity and rigidity further underwent “gradual mellowing” with Raja Kirpal’s death in 1693. It also influenced migration to nearby regions like Chamba, Jammu, Nurpur, and Guler, resulting in the rise of various styles of paintings like Kangra and Guler by the mid-18th century. Therefore, C. Singh asserts that using the term ‘Basohli’ focuses on the “decorative traditional style of painting in the hills”.

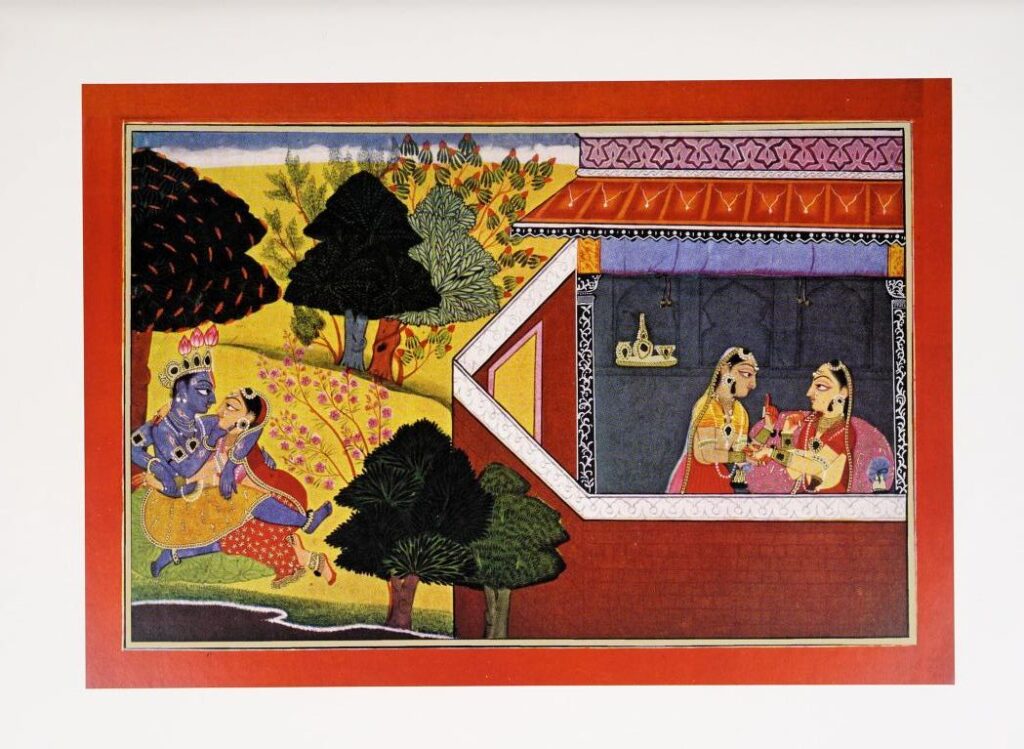

It was Gita Govinda by painter Manaku that determined this change. Written by Jayadeva, Gita Govinda is a prime example of Krishna’s representation as a cowherd and his relation with Radha and other gopis. In the painting The Ecstacy of Love (1730), Manaku provides a colourful and passionate expression of love. Krishna and Radha are seated under the Jamun tree, passionately gazing into one another. They are oblivious of their surroundings wherein one gopi is narrating their lovemaking to another gopi. We observe women wearing ghagra, dupatta, and choli. The presence of flowers and trees symbolises euphoria while the yellow background symbolises warmth. There is smoothness in the figures including their lotus eyes and noses and ornamentation.

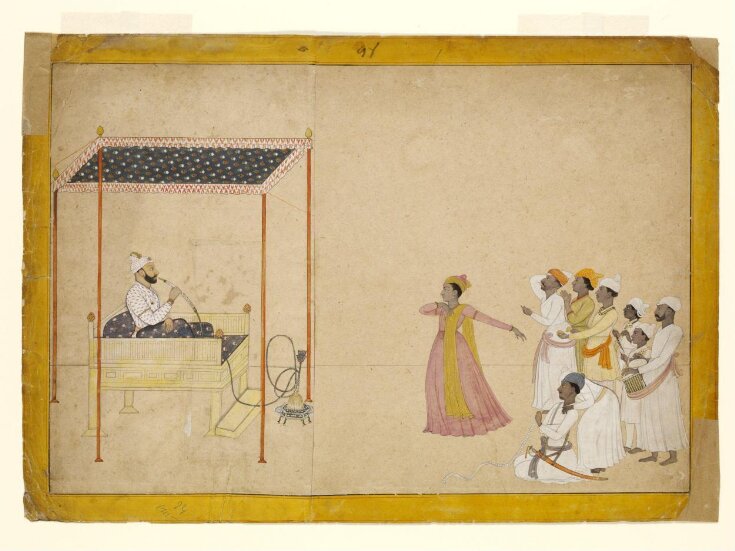

Another significant change is the growing prevalence of Mughal naturalism in the use of soft and cool colours. Aside from Manaku, Nainsukh was another great Pahari artist who worked against the Mughal-influenced style. In the painting of Raja Balwant Singh of Jammu (1750) Balwant Singh is smoking his pipe while watching a young male dancer mimicking the action of female dancers while surrounded by a group of singers and musicians. Mughal influences are prevalent in the form of themes, colours, figures, and clothes.

Against the resurgence of these Mughal influences in Basohli paintings, the Kangra style of painting would become a predominant means of expression. Thus, while the rigid and primitive Basohli style would subsequently lose its prevalence amongst the painters and patrons, there is no denying that the essence of Pahari culture and landscape would continue to remain prevalent in Pahari paintings.

I like this site very much so much great information.

Hmm it seems like your site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any recommendations for inexperienced blog writers? I’d certainly appreciate it.