From the 6th to 9th centuries, a religious movement called the ‘Bhakti Movement’ occurred in the Tamil country. The ‘Nayanars’ or ‘Nayanmars’ or devotees of Shiva and the ‘Alvars’ or devotees of Vishnu played significant roles in this movement. The bhakti movement witnessed the widespread participation of women saints. These women saints were either the conformists, i.e., daughters, wives, or sisters of male saints, or rebels who broke every norm of the society, including the discarding of clothes and redefined the idea of the domestic and outside worlds.

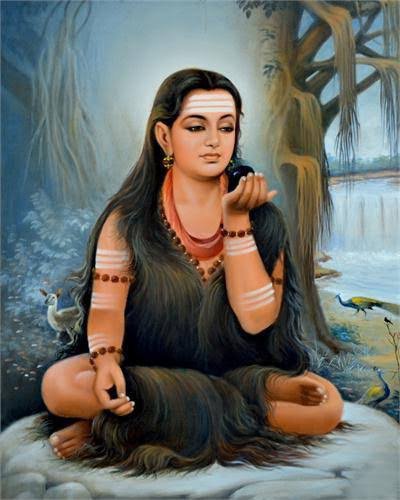

In early medieval India, the prime factors behind the exploitation of women were the lack of education and economic independence (interestingly, only prostitutes had both). In short, the role assigned to women was that of an obedient daughter, a chaste wife, and a sacrificing mother or, alternately the prostitute. The traditional society provided no scope for freedom or self-expression of women. The spiritual path of bhakti helped them to break free from all stereotypes. It provided women with the release of self-expression that the orthodox Hindu religion and the patriarchal society denied them. Women broke out of the shackles of tradition, orthodoxy, and convention that attempted to control their sexuality and sought God either as a skeletal being (Karaikkal Ammaiyar) or a naked saint (Akka Mahadevi).

In Northern India, women saints were considered ‘mad’ and ‘shameless’ and did not gain recognition during their lifetimes. However, the situation in Southern India was in stark contrast to the situation in North India. In the Southern part of the subcontinent, women saints emerged in an atmosphere of oppression and discrimination but blossomed into great scholars, thinkers, and realised souls. They were greatly revered by their followers and peers, both during their lifetimes and after their deaths. There is a noticeable feature regarding the participation of women in the Bhakti Movement in South India. Most of the women came either from the highest social class, i.e. women belonging to the priestly classes who had access to some sacred and secular, education, or from the lowest category, i.e. the Shudra class, in which women were economically almost equal to men. The very emergence of these women saints can be considered a social revolt in itself.

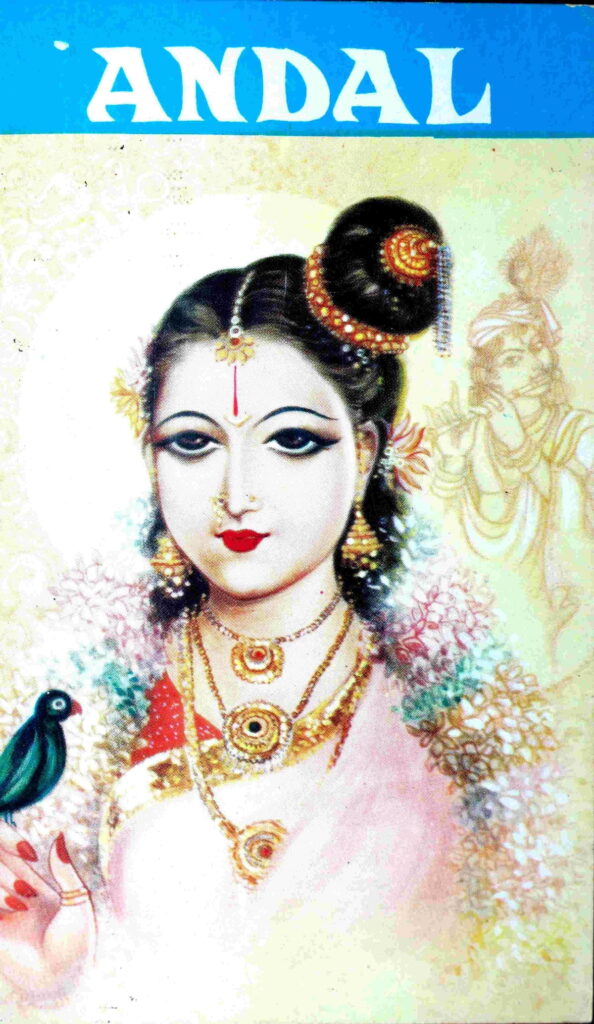

There were two types of female saints – one type was the conformists or the ideal stereotype of womanhood (the pious and chaste housewife) like Vasukiyar, the wife of Tiruvalluvar; the other type consisted of rebels like Akka Mahadevi. Located between the two ends of this spectrum were the saints like Karaikkal Ammaiyar, who gave up their conventional styles of living only when driven to it and had no other option. There were various reasons why the rebel saints broke free from the stereotypical mother-daughter-wife dynamics. Ill-treatment and torture after marriage caused many of them to renounce the world and take to the path of bhakti. Another cause of renunciation was the unnatural husband-wife relationship, for instance, the husband of Punitavati (later known as Karaikkal Ammaiyar), called Paramadutta, was so afraid of her spiritual powers that he could no longer look upon her as his wife. He disappeared and settled in Madurai with another wife. When Punitavati was brought to him, he fell to her feet with his new family seeking her blessings. This incident portrays a reversal of traditional gender roles as it is generally the wife who is expected to serve and worship her husband. When Paramadatta renounced all claims on Ammaiyar, she gave up her beautiful earthly body and assumed a fearful skeletal form. Apart from these two types, there was another category of women saints who never went through a worldly marriage and considered themselves to be the brides of the Lord, it was not merely a metaphysical relationship but a physical surrender of oneself; body and soul, to one’s divine husband. Akka Mahadevi’s verses express this intense love. Another female saint, Andal, considered herself to be the bride of Lord Sriranganatha (Vishnu) and daily fashioned a garland for the Lord, earning the name of Kodai (meaning garland). She is said to have merged with the Lord of Srirangam.

Unlike their male counterparts, women saints were completely free from all inhibitions. They did not recognise the gender binary or suffer from body consciousness. Akka Mahadevi, for example, discarded all clothes and covered her body only with her long, luxurious hair. The ritual taboo on female pollution during their menstrual cycle was broken by Karuramma, who entered the sanctum sanctorum and engaged in worship while she was menstruating. Women saints left their homes and freely mingled with male saints and scholars. Their compositions depict freedom from material things, gaining spiritual bliss, as well as alienation from society and personal loneliness. Both alienation from worldly pursuits and social alienation led them to be non-conforming women. It is hard to believe that in an age when women were confined behind silk veils and concrete walls of their households, a prominent women saint like Akka Mahadevi – the naked saint existed who was in fact a leading member of the Virasaivite Council of Saints in South India; or that at a time when poets eulogised the beauty of their fair-skinned, dainty lady-love, a female saint like Karaikkal Ammaiyar who was referred to as ‘peyar’ or demoness because of her fearful form, not only lived among the people of a highly conservative society but was also highly respected by her followers. Both the conformists and the rebel saints are equally respected in modern times. By rejecting existing social structures and flouting behavioural modes, these rebel saints have redefined societal paradigms about women’s roles and have altered conservative attitudes and transformed the bhakti movement into a social reform movement.

Bibliography

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. Rebels – Conformists? – JSTOR. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft MbH, www.jstor.org/stable/40462578.

Hello. Great job. I did not imagine this. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

Thank you so much.

Some genuinely nice stuff on this site, I like it.

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon on a daily basis. It will always be interesting to read through content from other writers and use something from their websites.

I just could not depart your site before suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person provide for your visitors? Is going to be back often to check up on new posts

you could have an amazing blog here! would you prefer to make some invite posts on my weblog?

You obviously know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Wonderful job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

my web page – tracfone special coupon 2022

Some truly nice and useful info on this site, as well I think the design and style holds great features.

Thank you!

Some really nice and useful information on this site, as well I conceive the pattern has wonderful features.

Glad to be one of several visitors on this awful website : D.

Very excellent info can be found on blog. “Never violate the sacredness of your individual self-respect.” by Theodore Parker.

This really answered my problem, thank you!