A typical feature of most historical scholarship is the pre-eminence it attributes to men as effectual participants in contemporary events. Men are portrayed as active agents and perpetrators with a direct hand in shaping the developments of their age and the consequences that follow. However, when it comes to the representation of women, matters stand in sharp contrast. Women have been potent partakers of history since time immemorial. However, only a small percentage of them find due representation in the chronicles of time. Additionally, where women do find representation, they are largely portrayed as ancillaries to their male counterparts, contributing to their cause. The most significant avenue where women are represented as agents of history is when they were used as accessories for the political agenda of men in that they were often central figures in stereotypes and propaganda fabricated to serve political ends. Foremost in this regard is the typecasting of women as domestic beings. The widely upheld Separate Spheres model conciliated and normalized the notion of the military proficiency of men and the exclusion of women from this domain. Yet another stereotype attached to women is female pacifism. Women are portrayed as being peaceful and pious, and hence, incapable of defending themselves in the face of violence. Consequently, it falls upon men to champion and defend the honour of these ‘helpless women’, particularly in the events of war and aggression. For colonial India, these trends manifested themselves in the historical accounts of the Revolt of 1857, a postulate that modern scholarship refers to as the Rape Script of the Revolt of 1857.

The Revolt of 1857 marked a watershed moment in the history of British colonial rule in India. Referred to as the Sepoy Mutiny in imperial discourse and the First War of Independence in nationalist terms, this was the first instance of an organized, large-scale agitation against the Raj. What started off as discontentment among the detachments of the Bengal Army soon transformed itself into a series of armed revolts that spread all over north India, most notably in Delhi, Cawnpore (now Kanpur) and Lucknow. However, such military and popular struggles tended to remain localized and divergent from one another. In the absence of a strong, centralized leadership, the movement was rapidly suppressed by the colonial forces with an unprecedented scale of violence and brutality. Millions are believed to have died by the time the Revolt was culled in 1858 and what followed was an aggressive restructuring of the colonial administration that subjected the native population to nearly a hundred years of a regime of unparalleled brutality.

Events in India came to garner a great level of public scrutiny in Britain at the time and it was in relation to this that the experience of the British women during the Revolt was used to legitimise and justify the actions of the British in India. Domestic imagery typically marked by depictions of British women and their households being defiled by native men came to occupy popular British imagination through newspaper accounts, parliamentary debates and visual images. Such narratives generally involved tales of ‘savage barbarians’ brutalizing ‘the delicate European woman’, the memsahab, which were disseminated through official government reports, local media and even popular fiction. As accounts of the death and suffering faced by their women spread in Britain, so did impassioned calls for vengeance. The Revolt came to be epitomized by the fate of the British women and the desecration of their bodies and their homes. Much of the British policies and practices, based on the rhetoric of racial and cultural superiority, that followed thereafter were largely portrayed as vengeance for the defilement of the British women at the hands of the ‘racially inferior’ Indian men.

Many narratives described the transgressions inflicted upon British women in lurid detail. In the Times, a letter from an ‘Anglo-Bengalee’ stated that “our ladies have been dragged naked through the streets by the rabble of Delhi. Quiet ministers of the gospel have been murdered. Their daughters have been cut into snippets and sold piecemeal about the bazaar”. The Illustrated London News painted “a ghastly picture of rapine, murder, and loathsome cruelty worse than death”, while Blackwoods Magazine described “horrors, such as men have seldom perpetrated in cold blood, outrages on women and children, atrocities and cruelties devilish in their kind—murder, treachery, rapine, mutiny—have been the expression of their rebellion”. Numerous accounts cited the ultimately unrepresentable rape of British women through hints and innuendoes.

The conception of the ‘violated woman’ emerged as one of the most ineradicable of all banalities concerning the Mutiny of 1857 that resulted in women becoming a “sexed-up subject of colonial discourse.” An interesting consequence of depicting British women as victims in the Revolt was the legitimacy that it provided for masculine retaliation against their ‘unmanly assassins’. Women were typecast as the tragic sufferers, only so their assailants, the native men, could be characterized as the unmasculine villains. Thus, the defilement of women was weaponized as an instrument to justify the brutal retributive measures taken against the Indian rebels.

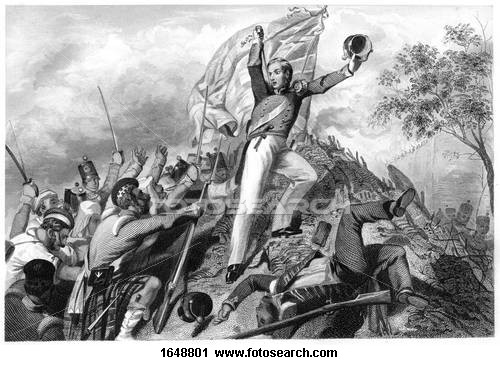

The conscience of the British public was effectively awakened by the rendition of the displaced and dishonoured British women, thereby enabling British retaliation to appear all the more virile and replete with pride in the face of Indian emasculation, the narratives of which were associated with discourses of honour. By committing obscenities against British women, ‘the masculine honour’ of Indian men was not only irreversibly impugned but also contributed to the image of the British male as the valiant and chivalrous defender of his country’s women. Within the framework of the masculine dialogue on honour, heroism and revenge, the eminence of the British army and its success in restoring British rule were inextricably linked to its ability to guard or to vindicate the honour of British women.

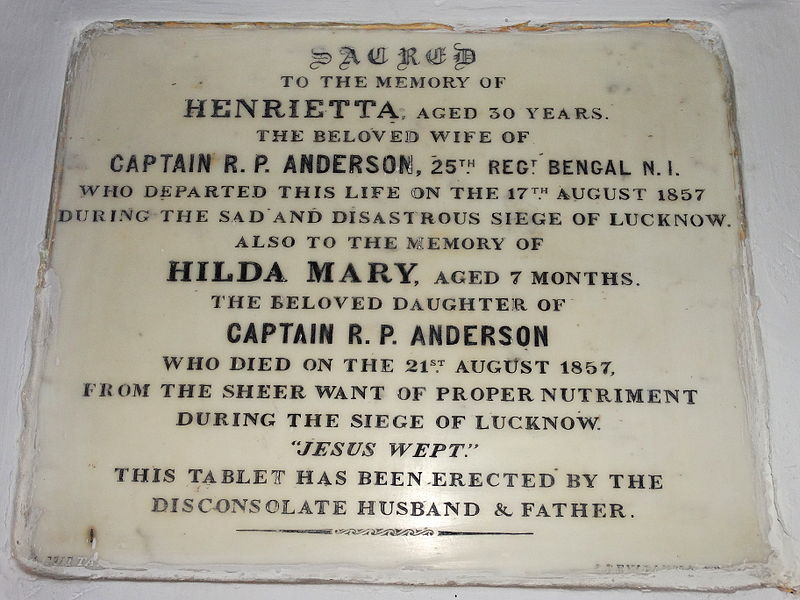

Moreover, during the uprising, the accounts of the experiences of the British women at Cawnpore and Lucknow were the subject of the most considerable parliamentary and popular scrutiny. Although located only 40 miles apart, the fate of British women at Cawnpore and Lucknow was starkly different. Whilst almost 200 women were killed at Cawnpore in July 1857, more than 200 women survived the siege of Lucknow that lasted from June to November 1857. British women who survived the onslaught of the imperial conflict at Lucknow were epitomized as symbols of piety and British honour. On the other hand, in consonance with masculine, national and imperial discourses of honour and prestige, the deaths of British women at Cawnpore stoked up calls for vengeance and brutal retaliation.

In the aftermath of the Revolt, the British authorities in India were compelled to undertake a considerable overhaul of the administrative and military systems. These changes were based on major ideological refurbishments in which the representation of women came to occupy a significant position. At first, the postulation of women’s defilement was utilized as a political device of despotism. Later, however, the narrative of British women being violated by Indian men came to be perceived as an acknowledgement of the rebels’ success in dismantling traditional racial and power hierarchies, and official accounts portrayed all such narratives as propaganda spread by the mutineers to quell British might. In this stage of denial, it became a tool for the restoration of order. Conclusively, the chasm that characterised the women’s position in 1857 was very telling – she was both the coloniser and the colonised.

Gunjan Mitra is an undergraduate student pursuing B.A. (Hons.) in History from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi. She is a firm believer of nature conservation, more specifically marine conservation. She is a certified Divemaster from P.A.D.I. She enjoys travelling and photography and hopes to be able to explore the history, culture and languages of people from all over the world.

I like what you guys are up too. Such smart work and reporting! Carry on the superb works guys I?¦ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my website 🙂

Great – I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Excellent task.