In India we have a staunch history of dissent; dissent that shaped even the dogmatic religious practices and protests that shaped the will of our modern nation. Our nation’s modern history is marked by Gandhiji’s solid presence and his call for Satyagraha and using protests to mark our dissent is not new to us; but for a nation who won independence through these means, today the word protest itself is taboo.

From the use of excessive force on peaceful protesters to the narrative we are fed of the unruly mob and the benevolent ruler who knows best, the tactics used by the erstwhile foreign rulers and the democratically elected government are eerily similar.

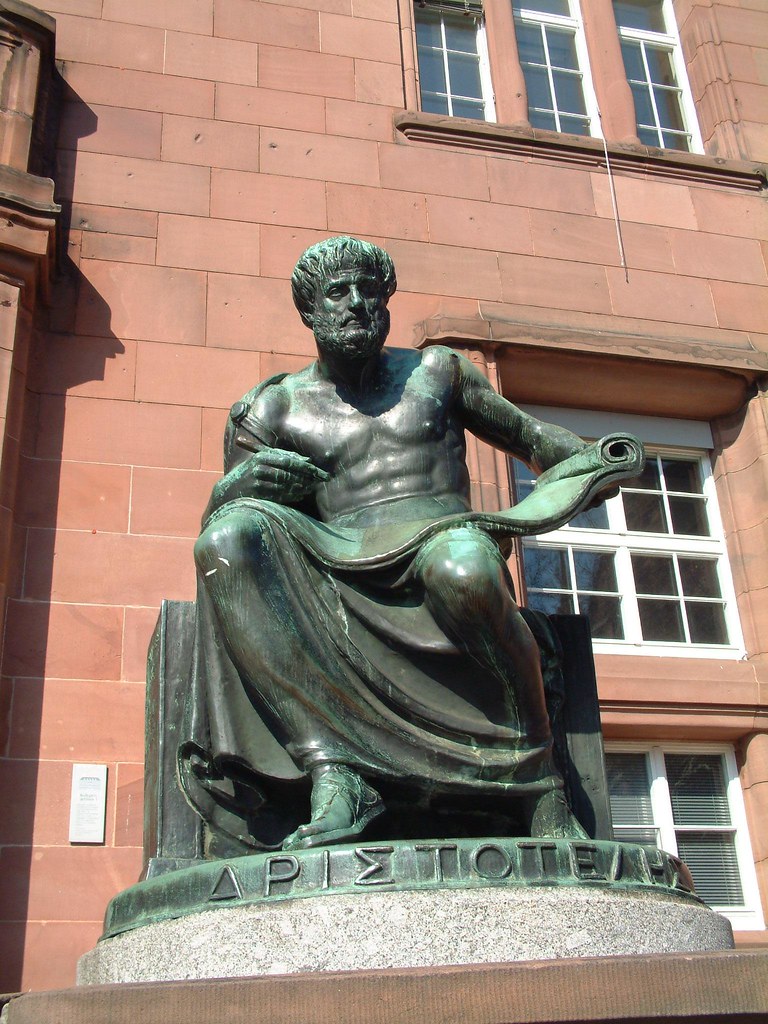

Interestingly it is almost always the Aristotelian idea of the unruly mob versus the good citizen that is invoked by those in power to criticise and end protests. Aristotle described the mob as a group of men lacking independence, mindlessly following a tyrant, who lacks rationality and discipline. And it is the mob that threatens the political order. While a good citizen, one who holds office and gives judgment, adheres to the constitution that governs his land and works towards its stability. He follows the law, irrespective of whether they are good or bad. Thus eliminating the ambit of protests and minimising dissent.

One of the greatest examples of the use of this strategy is the trivialisation of the ongoing protests by the farmers’ collective in India. On the twenty-seventh of September, after ten months of protests, the farmers’ collective in India organised a nationwide bandh to mark the anniversary of the largely unpopular farm laws. The three laws namely, the farmers agreement on price assurance and farm services act, the farmers’ produce trade and commerce act, and the essential commodities act touted as monumental laws for modernising agriculture and empowering the farmers, have in reality led to a huge section of the farmers protesting against them. The farmers, especially the medium and small land-owning farmers, have worries that these laws could very well lead to a loss of livelihood for them due to excessive competition from much larger players and the eradication of the minimum support price. The large-scale ongoing protests in the capital city are to mark their dissent against these farm laws and to call for a timely solution for the many problems that the farmers currently face.

Agriculture employs almost 1.3 billion people and contributes to fifteen percent of the GDP in India. But the many problems they face with no imminent solution in sight has led to our country’s agricultural sector facing its greatest crisis since the green revolution. From falling yield per hectare of land, the gap between what is demanded by the consumers and what is produced, the huge buffer stock of food grains in government warehouses to the scarcity induced price hike of vegetables in markets for the consumers which rarely translate to profit for the producers, ecologically unsustainable production leading to water and soil degradation, debt crisis among the farmers which lead to increasing rates of farmer suicides and the lack of infrastructural development in rural areas are some of the myriads of problems afflicting the sector. The frustration of the ones who feed the nation following this has culminated in this long-running protest.

Modernisation and the shift of labor away from agriculture to manufacturing dominates the literature in development economics as the way forward for countries like India. But this transition is anything but smooth; the fears of the smaller farmers that they will not be able to compete is real, and losing their current source of livelihood is a possibility. Homogeneity and uniformity is not an Indian characteristic; from our culture to language and food practices we see a heterogeneous blend. This is certainly true of agriculture, the many generalised problems mentioned here cannot cover the additional problems farmers face in each locality, thus a single solution for the multitude of issues is unrealistic, neither is a single law realistic. A community-based and community-involved plan based on the many in-depth surveys is the way forward for us.

In the face of these problems, trivialising and infantilising the protest and likening them to this Aristotelian idea is diplomatic, which achieves no solution and would only enrage the aggrieved. Interestingly when evoking these political ideas we often ignore Aristotle’s definition of a good man, one who possesses both practical and theoretical virtue, and he on account of his virtue would not follow the bad laws thus becoming a bad citizen. Thus the aim of politics he says is to bridge this gap or to bring into unity the good man and the good citizen. If we are selectively following the ideas of philosophers when it suits us, why don’t we, the citizens, follow this instead? Because to go forward with this aim of politics, we could most definitely create a better world more suited for everyone where we listen to the dissenting voices and find solutions together.

Induja Thampi

Induja Thampi completed her undergraduate degree in economics from Lady Shri Ram College and is currently doing her post graduation from Central University of Tamil Nadu. She loves to read and believes in humanity's ability to right its wrongdoings. With a pen in hand and a few trusty books at her desk she tries to go about doing just that, wherever injustice prevails.

wonderful submit, very informative. I wonder why the opposite specialists of this sector do not

realize this. You should continue your writing. I am confident, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Relying on your instanct is tough for most of us. It takes years to build confidence. It doesnt really just happen if you know what I mean.