If you see a Hindi film, you don’t think about poverty or India’s third world status – Mammootty.

Art for a long time has afforded human sensibility with numerous ways to explore and express the imagined and the real. The scope of artistic venture thus has always been an ever-expanding phenomenon whose manifestation has ranged over time from paintings to music and dance, to theatre and the most recent addition being the cinema. According to Martin Scorsese, “cinematic innovation is by far the most complex, collaborative, and costly artistic expression.”

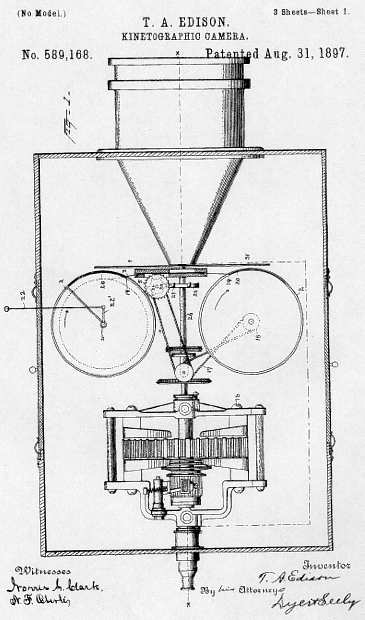

The invention of the initial version of the film camera known as the kinetograph is credited to Thomas A. Edison and William Dickson in 1891. Inspired by them, Louis and Auguste Lumiere in 1895 famously created the ‘Cinematographe’ that radically changed the form of entertainment and influenced popular culture. The creation of a large screen for the projection of moving images created an environment of shared experience for the viewers.

The world welcomed the birth of the first “movies”. A year later on 7 July 1896, the screening of six films at the Watson Hotel in Bombay (now Mumbai) by the Lumiere brothers eventually ushered in the era of motion pictures in India from which there was no turning back.

However, films in colonial India, especially as a mode of ideology, were affected by censorship, degrees of popular acceptance and elite preferences that conveniently deflected any artistic venture. Consequently, religious idioms were extensively utilized for expressing the class perceptions of tradition to the exclusion of cultural alternatives. The constructs of myth, history and a nation under upper-caste middle-class supervision were codified onto the silver screen.

While the contestation to political colonialism ended with the partition and independence, Hindi cinema took recourse to conventional heterosexual love, patriarchy, family and nation-building from the earlier allegorical depictions of historical conflicts. These were to become the elemental constructs of the national project which was quintessentially a bourgeois obsession in a former colony. Indeed, independence from British dominion propelled the Indian bourgeoisie to power thereby starting the process of nation-making in India. Integral to this transformation was the role of mass media and as one witness, the social project of cinema was intimately connected to the bourgeois imagination of the nation-state. As professor Anirudh Deshpande puts it, ” The more apolitical a film pretended to be, the greater was its political significance, after colonialism commercial cinema aimed to reorder society in the interest of the elites empowered in independent India – cinema became the opium of the masses after 1947″.

Globalization in effect resulted in the commercialisation of Hindi cinema which promptly expanded its outreach to a greater mass. Post-1960’s witnessed the burgeoning rise of “celluloid fashion” and the Indian television life with a series of regional units producing linguistically specific programmes. However, cinematic realism featuring the subaltern components of the society remained elusive in the mainstream national depiction.

Why the poorer sections did not patronise such films is a question unanswered. If commercial Hindi cinema succeeded partly because of the hegemonic underpinnings of the bourgeois in India, the question is easier to answer. The bourgeois setting of Hindi cinema is equally appealing to the subaltern classes, as is Hollywood to the Indian middle class. The hallucinations projected by Bollywood quintessentially become expressions of popular aspirations. Thus, to identify with the dominant culture of our period the lower classes mimic the bourgeois.

Then, the claim that the Hindi film industry is a melting pot of cultures and an example of Indian secularism is not completely true. As pointed out sagaciously by Dr Deshpande ” Hindi films are neither politically innocent nor conveys unequivocal secularism; its “social” film is predicated upon the politics of inequality and escapism. In matters of gender, reason, science and modernisation, Hindi cinema is reactionary. It usually panders to the vulgar to maximise returns”.

However, all hope is not lost. Bollywood, over the last 20 years has witnessed counter-hegemonic correctives in Hindi and other languages. Particularly, the realm of parallel cinema or innovative cinema, that focuses on ordinary events of the ordinary people; underplays the dramatic; remains open-ended; uses natural lighting and sets and retains the ambiguity of reality has increasingly found its voice in the cinematic universe. Of special attention is the Assamese cinema whose contribution to the making of the heterogeneous Hindi cinema is to date undermined.

From its very first release in 1935, film producers in Assam had a clear undertone that inclined more towards the serious modes of film-making by focusing on the new socio-political realities of an independent India while simultaneously embracing the more respected techniques and approaches of film-making. The works of Padum Baruah, like Gonga cilonir pakhi and Jahnu Baruah stand testament to this fact.

source: Times of India

However, Bhabendra Nath Saikia (1932–2003) who is credited with the creation of seven films in Assamese and two in Hindi, is considered the most prolific amongst this lot.

Saika has created a world in his movies that is quintessentially ordinary. From Sandhyarag to Itihas, his is a faithful mimicry of the real world with the equally persuasive establishment of the crisis in the protagonist’s world. His oppressed protagonists never attempt at overturning a situation by protest or revolt but try to seek solace within the system itself. His narratives transcend the conventional heteronormativity and culture escapes to take us into a world that is very real. For instance, the only Saikia film of Saikia where a protagonist is a man instead of a woman is Sarothi (1992) and in Kolahal too, we encounter characters like Binod Patowary who hails from Muzaffarpur and Master Uncle who sings weird Hindi songs. These are unmistakable symbols of an emerging globalized and commercially connected nation space.

Over the last few years, parallel cinema has indeed received international recognition, but its stronghold on the home soil remains feeble, partly because Hindi cinema has apportioned shares of nationality among India’s diverse communities while continuing a long-term relationship with Hindu nationalism which has emerged as the dominant ideology, much to the neglect of the marginalized. It is time we learn to read between the lines and not blindly follow what’s given. A discolouration of our conscious imaginations from the conventional narratives and a greater appreciation of the subaltern space and history will only be the true representation of our identity in both the real and reel life.