Through millennia, the world has witnessed major cultural and optical intimations, following gross political upheavals all across the fore. A brief look at the past acts of iconoclasm, cultural defiance, will tell us that there is no civilization on the face of the earth untouched by forces looking to rewrite, amend, erase its history.

Images, particularly from the bygone year, have presented evidence to a raging discourse, underlined with a revived fervour to ‘correct’ historical wrongs. The ambition to place the burden of today’s popular imagination on history’s artistic marvels has swept the world by a torrent – statues, buildings, plaques, ‘problematic’ places of worship, continue to be defiled, demolished, dismantled and defaced as a matter of political importance. In the year 2020 alone, the United States saw the removal of nearly a hundred statues symbolic of the Confederate leadership, or erstwhile colonial and racist ideologues, a pattern which was repeated in almost every continent in the world.

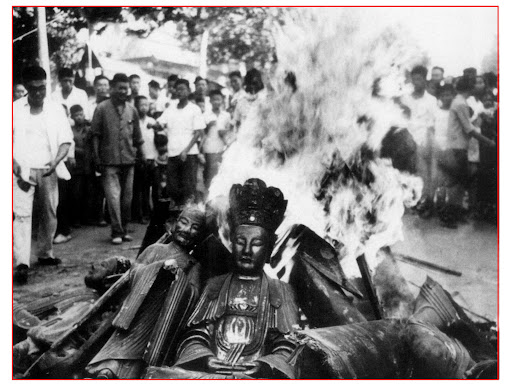

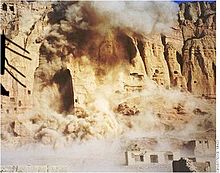

Recognised for their symbolic value, aniconic actions from history – be it the state-sponsored disposition of old relics and symbols in the Byzantine era, or the destruction of the Four Olds, ideas, culture, habits, customs, by Mao’s Red Guards in the 1960s, or even the Talibani demolition of the Buddhas in Bamiyan in 2001 – are all loud expressions of a silent, contrary truth, signifying shifts in the mainstream cultural and political paradigm.

From the vandalism of Hindu temples and idols by Islamic invaders in medieval India, to the demolition of the Babri mosque by the vanguards of Hindutva in 1992, the practice of desecrating sites and signs of religious and cultural importance is not new to India either. In fact, these acts are spread across entire lengths of space and time.

As ideas interact with ideas, clash and rebound, it is inevitable that some actions perverse to the opposition’s strongly-held beliefs will aggravate inter-cultural and ideological conflicts. Amidst all this, we must question, not just the secondary logic of destruction and erasure, but the primary one of creation as well. Why are these icons – images, statues, edicts and monuments – erected in the first place? Why does history cement people on the high-pedestals of legacy? What do these symbols of the past signal for the present and the future? Indeed, physical iconography is, in a way, a means to confirm the foray of an idea from paper to practice. Constructed by law, by force, or by fact or fate, icons represent the triumph of a man or an idea over another; the ritual, ceremonial ratification of this victory before a crowd of, perhaps, a divided public. In the same sense, the inauguration of a statue is as symbolic as its performative destruction.

Should these statues, obelisks of ideas, be preserved for an eternity, or be pushed into oblivion as symbols of antiquity, their removal marking a generational, historiographical shift of thought? In that case, what, and who, is to determine the underlying criterion for such preservation and destruction? Neil Van Leeuwen, philosopher of mind at Georgia State University, weighs these questions in the light of former President Trump’s rhetoric against the demolition of Confederate statues. Trump asks whether the statues of America’s Founding Fathers should meet the same fate by virtue of the fact that these men happened to own slaves in antebellum years. Leeuwen agrees with this rationale, if the statue, the symbol, depicts the egregious action of slave-owning at play. He says, “Public monuments don’t just commemorate people; they also commemorate actions…”

However, in the broad spectrum of reality, meanings and interpretations are wide and diverse, making the question harder to resolve. The act of destroying a physical representation of an idea satisfies the physical and symbolic conditions to erect another, almost in the sense of imposing it on an oppositional class. All given examples of iconoclasm, mentioned in this article, have a symbolic meaning for both the sets of stakeholders, those facing defacement and those being ideologically glorified by the public destruction of its opposite counterpart. Often in these matters of ideas, ideologies and immaterial cultural sentiment, polar-opposite perspectives emerge, often unwilling to reconcile on a middle ground.

To a crowd of millennial protesters in North America, the statue of Christopher Columbus represents the glorification of a colonial, racist history, with the cultural revolution starting with its most obscene removal. Contrarily, to a conservative American, his edifice represents the great continental discovery and the onset of a globalised age, its destruction a product of gross ‘anachronism’, with the ideals of a post-modernist world seen as being unreasonably applied to the conditions prevalent during the Dark European Ages. To a student active in the 1960s Maoist China, the erasure of old totems might imply the coming of a communist era, a ‘Great Leap Forward’. From an opposite lens, the unquestioned obliteration of an entire culture signifies the hideous brutality of communist violence. And to the Taliban, the demolition of Buddha effigies might’ve meant a triumph over pre-Islamic idolatry. To the world at large, it was an expression of cultural terrorism, the fact that the polar opposite worldviews would never be able to forge a peaceful coexistence.

When we delve deeper into this perspective-led dichotomy, the recent instances cater us better. In the most recent case of, what is being touted “vandalism,” over 50 Catholic Indigenous Churches across Canada were immolated and desecrated during the months of June-July, 2021. The incidents transpired following the shocking discoveries of unmarked graves on the sites of indigenous boarding schools, over which these churches were built. More than 1000 dead bodies of, mostly, young children, were also found, inducing a wave of shocking, but not surprising, horror. After all, the world at large has grown up hearing of the atrocities committed in the name of Jesuit missions, but the unscathed nature of these revelations added on to an already-building fervour against the iconography of the colonial and post-colonial oppressor-type.

However, the indigenous communities in question have called these acts of vengeance, “acts of terror,” condemning them as unwarranted attacks on their personal religion and dignity. Prime Minister Trudeau was called into question for his mild words of censure, just as people of the indigenous communities rose to shun these cases of arson as causing “strife, depression and anxiety,” as they mourned at the heart-wrenching revelations. The dual imagery that this destruction creates in our minds is worth paying attention to. On one hand, these churches represent the faith of their ancestors, the faith that has passed on to the current generations. On the other, they stand tall as symbols of grotesque oppression and past erosion of the indigenous cultural identity.

In another series of incidents across the Western world, starting from Washington DC and running to Ottawa, Amsterdam, and Leicester, protestors toppled and effaced the statue of MK Gandhi, in the light of the renewed discussion on his racist views of the native African people. Past writings of his show that he differentiated between the Indian and the ‘kaffir’ African in his civil rights campaign in South Africa.

The aspersions cast on his stature aren’t new. Previously, in Ghana and Johannesburg, his busts and figurines have met with aggressive scrutiny, and statues removed on their historical-moral question in the postmodern world. Each time that has happened, a new debate on his contemporary relevance has struck across political circles, especially in India, wherein he is revered as the face of non-violence and anti-colonial fervour that got India its freedom. Others also defend his stance bringing out the fact of his ignorance and the fact that he reformed as he grew into a mass-leader.

It is obvious that in the relative archives of history, a hero in one culture is an assailant for another. CGTN, in a news report, poses similar questions – “Who gets to judge Gandhi’s legacy? Protesters on a mission to remove his statues or historians who have analyzed his work and life for decades? And where does it stop and with whom? In a free fall, will there be a last statue standing?”

Indeed, who is to take these decisions? Are they to be adjudicated by government-ordained historians, or are they to be left to the court of public opinion, which by itself is temporally defined? There is, perhaps, a way above violent displays of disaffection – rewriting history in the most literal sense.

In his critique of the image as a mirage, as the most fallacious representation of reality, Plato denounces icons, symbologies and everything taken as a semblance of the original, as one that reduces reality to a prison of limited mental perceptions and ideas. But he was kinder to the written medium, including written philosophical deliberations as well as historical accounts, but he mandated that these written scrolls must carry messages of moral wisdom. Both him and his contemporary, John Dewey, believed in the power of the written word, of education, in giving society a new constructive face.

The idea of incorporating moral virtues in reading material of young minds seems enticing, particularly when it comes to the study of history. It has often belied the ways in which the study of history has been co-opted by forces that have moulded it in uncertain directions, implanting strange ideas among the mass readership, in the name of what is just and moral. Notably, the subject, that is history, has been a historically politicised and contentious one, almost as if representing an active marker of the long-stretching battle of ideas and the battle over who gets to frame the reigning discourse of the day.

The debate over the teaching of slavery and Black history in the United States takes another form as the debate on distorted history readers in Pakistan rages on. In India, history curriculums have taken a centre-place in major discussions around the state of education in this country. What needs to be fed to our children, who decides what facts need to be expanded, what needs to simply be mulled over and what is to take precedence in a gamut of phases and chronicles giving meaning to an unlived past?

There is also a problem in answering whether Plato’s idea of disseminating morality through paper can be given a root in the way India teaches history, given that the current political context is mired with strong sentiments and biases from all four corners. It is not a surprise that every year the University Grants Commission of India introduces revision of syllabi. Ironically, the factual nature of history is often the first one to fall prey to this new iconomachy against the old, guiding facts and figures providing legitimacy to a perceived ideal. The restructuring of curriculum across the globe represents the elite-led vigour to bring in a new cultural revolution of our times – with the displacement of old ideas with new ones, reflecting the ethos and pathos of an ever-changing world.

The philosophy of education and iconography may sound abstract and complex, and it may be difficult to answer the epistemic questions over the supremacy of ideas. But creation and destruction are processes of nature. Icons, tangible and metaphorical, have been created and will be created, have been destroyed and will be destroyed in ways human or natural, democratic or totalitarian. History will continue to be reshaped by the victors of their age. The question is – whose history are we reading, breathing, anyway?

Samridhi Chugh is a final-year student of Journalism with Political Science at Lady Shri Ram College for Women.

Interested in exploring the confluence of law, policy and print media, she tends to use the written word as a conduit for her scattered emotions.

She aspires to pursue legal journalism at a near future.

Yoga cann be used as a natural method to cue insomnia.

Yogaa is a exercise that helps people loosen up in order to assist

with sleeping. It educes stress and panic that may be keeping throug sleepiing well.

Yoga exercise also helps with relaxation before bedtime.

Yogaa for sleep is an ancient practice through India that has been useful for

thousands of years. It came abouht because of how the real poses help activate various points within thee body, while breathing methods bring

balance towards the mind and body. These ttwo ideas work together to crrate a express of tranquility where

one can achieve a deep state of relaxation, or sleep, and possesses

been proven by scientific research as well.

Pilates ccan be used as a all-natural method tto cure sleeplessness.

Yoga iss a ptactice that helps people unwind in orrder to

assist with sleep. It reduces stress and panic that may be keeping through sleeping well.

Yoga exercises also helps with leisure before bedtime.

Meditation for sleep is an anmcient practice via Incia that has been used in thousands of years.

It came into being because of how tthe rewl posses help stimulate various pokints in the body,

while breathinng strategies bring balance to the mind and

body. These two principles work together to crerate a point oout of tranquility where

one can achieve a strong state off leisure, or sleep, and it has been proven by

research as well.

Lots of people have heard about the magic of rice normal water shampoo, but many are still wondering how it can help your

hair. Rice drinking water helps with hair as a result of nutrients that are found in rice water, especially vitamins A,

At the and D. Supplement A is important with regard to hair growth and can assist strengthen the hair follicles.

Vitamin D is necessary intended for healthy skin and will help prevent dandruff and eczema.

I read this article fully on the topic of the difference of most

up-to-date and earlier technologies, it’s remarkable article.