India just celebrated its 75th Independence Day this year on 15th August. To commemorate the momentous occasion, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has urged all Indians to take part in the year long celebrations that are being organised as part of the ‘Azadi ka Amruta Mahotsav’ programme. The celebrations are scheduled to continue till next year’s Independence Day.

It is however far from being clear whether around 19 lakh residents of India’s northeastern state of Assam would be able to embrace the occasion? This is because their eligibility for Indian citizenship is currently under question. They are staring at the catastrophic possibility of being rendered stateless. This is because this group failed to have their names included in the National Register of Citizens (NRC) at the culmination of its updating exercise in 2019.

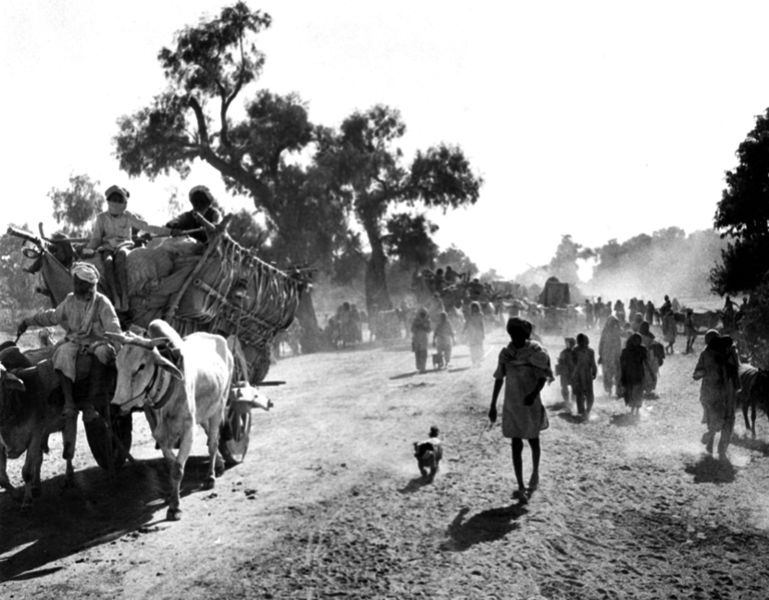

The original NRC was drafted in 1951. British India’s partition into two dominions led to large-scale migration of Bengali Hindus and Muslims into Assam. This generated considerable apprehensions within native political opinion, which felt that such settlement would be detrimental to indigenous interests. It was therefore to placate such anxieties and check unregulated immigration in future that a register containing a list of citizens of Assam was prepared.

However, the clamour for updating the NRC only began to grow louder as the Assam Agitation gathered momentum. While this demand could not find a place in the Assam Accord signed in 1985, Assamese subnationalist pressure groups often reiterated this demand from time to time. It was eventually in 2005 that the Union and Assam government conceded to update the NRC.

Most people hoped that updating the NRC would pave the way for detecting illegal immigrants who were in the state. This was of course premised on naïve optimism and was oblivious of actual challenges on the ground. It was basically thought that those who are genuine citizens would be able to give documentary evidence of belonging to India on the basis of which they would be included in the NRC. On the other hand, the excluded would be those who could not provide evidence of the same because they have been illegally staying in Assam.

The exercise of enumeration was therefore to function simultaneously as a system of identifying illegal immigrants. A logic of exclusion therefore got inevitably built into the process.

At one level, such a logic arose out of the design of the updating exercise. The NRC relies on documentary evidence for ascertaining the citizenship of an applicant. But most Indians, especially the poor, uneducated and women simply do not possess such records adequately. This inability to produce proper or correct documentary evidence now threatens to turn the excluded “from rights-bearing Indian citizens to grovelling, effectively-stateless subjects”, says Dr. Nayanika Mathur who is currently teaching at Oxford University. But the inability to provide satisfactory documentary records certainly do not directly imply that such individuals are foreigners.

The exclusionary impulse of the NRC was further reinforced by the considerable degree of cultural bias that appears to have shrouded the updating exercise. In the course of the process, this perhaps became manifested most clearly in the context of the controversy surrounding the entry of ‘Original Inhabitants’ (OI) in the Register. The provision is included in the Citizenship Rules 2003 and in the NRC enumeration it basically “offered an alternative categorization for inclusion of a section into the NRC without as much documentary evidence as some other would need… ”, wrote Abhishek Saha in his book, No Land’s People. Such biases are rooted in a more generalised prejudice against certain groups of people due to their cultural affinities with people across the border. This imposes additional hurdles on many genuine applicants who have consequently struggled to meet the criteria for inclusion in the NRC.

Despite the strong exclusionary thrust of the updating exercise, all the major stakeholders have rejected the final NRC. Why? Because they feel that the document is erroneous as the number of exclusions is quite small. It is as if according to them a correct NRC is one that makes a higher number of exclusions. But since no prior exercise to determine illegal immigrants was undertaken, such complaints of low exclusion are based more on their guesswork and conjectures instead of any objective criteria.

Most stakeholders however are now demanding a re-verification of the NRC inorder to address the apparent errors. The Assam Public Works (APW), a prominent pressure group associated with the updating exercise, has filed a petition in the Supreme Court demanding 100 per cent re-verification. Even the Government of Assam has petitioned for a 20% reverification of NRC in bordering districts of Bangladesh and 10% in all other districts. Not only this, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) pledged a “corrected NRC” in its election manifesto for Assam. After coming to power, the new chief minister reiterated his government’s commitment to re-verify the NRC. But while the government is now showing much enthusiasm for correcting the NRC, during the verification stage before final publication, it chose not to exercise suo-motu powers of investigation regarding the same. The Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) guiding the updating exercise allows the government to use Local Registrar of Citizen Registrations (LRCR) to re-verify names already included in NRC.

Re-verification of NRC would compel many to go through the ordeal of proving their citizenship once again. Just a few years ago, these people had undergone a similar test, often at the cost of considerable emotional, physical and financial costs. Some had to forgo their livelihood assets and jewellery while the more unfortunate ones even lost their lives. Many others also lost several days of wages while moving around trying to prove their citizenship.

Two years have passed since then. But till now the excluded have not yet been able to challenge their cases. Neither has the Registrar General of India (RGI) notified the NRC nor have the Rejection Slips been issued. Certain pressure groups and the government perhaps desire to create an even wider whirlpool of misery and suffering by proposing fresh re-verification of NRC even as nineteen lakh people are already on the brink of statelessness.

For many in Assam, especially if they are poor and belong to a linguistic and religious minority (say, Bengali Hindu or Bengali Muslim), the quest for citizenship could be an elusive journey for them. It is quite probable that at the end of the road, instead of being acknowledged as a citizen of the state, they would be once again confronted with a newer set of tests to determine whether they actually belong to this land.

Abhinav P. Borbora

Abhinav P Borbora teaches Political Science at the Assam Royal Global University in Guwahati and can be reached at abhinav92ac@outlook.com.