The Census is the system through which a country collects, compiles, analyses and disseminates the demographic, social, economic and cultural information of its citizens at periodic intervals. In India, the population Census can be viewed from two different standpoints. First is the “static aspect” which provides an immediate picture of a community that is authentic at a particular moment of time. Second is the “dynamic aspect” of the census which provides the trends in demographic elements. In a country as diverse as India, organising a population census is undoubtedly the biggest administrative exercise. The plethora of information collected through the census on the households, socio-economic and cultural features of the citizenry makes the Indian census a rich source for policymakers, research scholars, administrators and other data users. It is the most important source of information on the political, economic and social affairs of modern-day India.

Interestingly, the concept of accumulating information on the population of a state has had a long history in India. The Rig Veda, one of the most ancient texts of the Indian subcontinent, provides evidence of some semblance of a population count being maintained in India during 800-600 BC. The much-lauded administrative text Arthashastra, written by Kautilya in the 3rd century BC advocates the collation of population statistics as a determinant for state taxation policy; the text contains an exhaustive description of methods of administering population, agricultural and economic census. During the rule of the Mughal emperor Akbar, Abu Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari included sweeping data related to the population, industry, wealth and other related aspects of the citizenry.

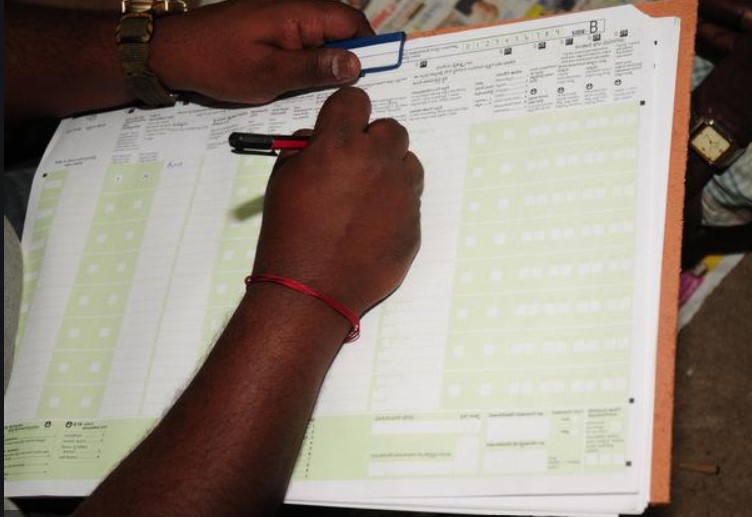

A methodical and modern population census, in its contemporary format, was conducted asynchronously between 1865-1872 in different regions of India by the colonial government. This undertaking which culminated in 1872 has been designated as the first population census in India. However, it was in 1881 that the first concomitant census was held in India subsequently, the Indian census has been conducted consecutively once every ten years.

The information collected through the census has a significant impact on the administration of India, particularly in the sphere of policymaking. One of the most fundamental administrative purposes of a census is the delimitation of constituencies and their corresponding governing bodies, intricate data on the geographic spread of the population is essential for this objective. Additionally, the legal and administrative standing of a territorial division is largely determined by the size of its population. The social and cultural information collected through census is an important deciding factor in the total number of seats to be reserved for members of scheduled castes and tribes in the Lok Sabha (House of People) and the Legislative Assemblies of the states in India. At the district level, the details collected via Census on the demographic and economic characteristics of the populace is an essential tool for the purpose of administration. Evidently, data on the geographic dissemination of the population, its size and other socio-economic characteristics is crucial to the research and examination of social and economic issues, which herald the formulation of policy influencing economic and social development. The deliberation of issues of employment and manpower programmes, migration, housing, education, public health and welfare, social services, economic and social planning, and numerous other aspects of the life of the country, are enabled if precise information about the features of the population is available for civil and other administrative divisions.

Although the Census count of the Indian population seems to be an apolitical affair, it is in fact coloured by political undertones of various shades. The information collected by the Census on socio-economic characteristics and demographic traits of the people is determined considerably by contemporary political concerns. Individuals who hold political power play the primary role in deciding congruous social classifications utilised for the census and for administrative purposes. In India in particular, changes in census groupings over time occur in tandem with changes in the definition of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and the relationship between the two. The census classifications not only reflect social identities but in many ways, also help in the creation of new social identities in harmony with the specific treatises of the major political parties in India. For instance, the new category of ‘scheduled castes’ was added to the Indian Constitution to replace the vaguely defined category of ‘untouchables.’ Furthermore, competition for jobs and other similar perceived concessions have their own part in reinforcing the census-created categories, which in turn, have important political implications.

Since 1947, the primary concern in India has been over the question of how to integrate and homogenise a nation as diverse as ours, significantly, the Indian political elite has adopted Brahminical Hinduism with its various facets, including the caste system, masqueraded as “mainstream” culture as the main motif in this regard. The notion of Indian “mainstream” is elemental in the process of homogenising the country’s socio-culturally diverse reality. The Census classifications have made their own contribution in this regard.

Nearly all the principal political parties in India, especially the Congress and the BJP have strived for the erasure of socio-cultural differences in the country. Their political discourses favour all-India structures over regional, and the mainstream over “regional.” The primary difference between the Congress and the BJP lies in the manner in which they operate within the overarching structure of Hinduism. The BJP, at least in contemporary times, seems to have the intention of destroying all signs of “non-Hinduness” in a combative and hegemonic fashion. The Congress, on its part, seems to be aiming at the subjection of the ‘Other’ to curb any effectual opposition to the mainstream thesis.

This is where the data collected through Census comes into play. Religion has been a recurrent and significant part of the data collected through Census since 1871. However, the particulars of the religious data have always been influenced and manipulated by the socio-political interests of the political leaders. For instance, after the Census of 2001, a number of important leaders of the Sangh Parivar condemned the “explosive” growth-rate of the Muslims. This data was wielded by the political right to create a narrative in which India’s vast population and its associated problems is an issue that can be traced directly to the Muslim community. Significantly, there are many adherents to this notion to this day. Instances include the 1983 Nellie massacre and more recently, the 2013 riots in Muzaffarnagar.

There are many instances of religious data collected through the Census being misused by political parties in present-day India. The most significant is the controversy surrounding the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA). This Act aims at providing Indian citizenship to “religious minorities”- who are Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs, Parsis or Christians- facing persecution in Islamic nations such as Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Glaringly missing in this list is the Muslim people in these countries. Additionally, there are many nations, such as Sri Lanka and Maldives, where Hindus have been persecuted for many years now. These countries however, have been excluded from the purview of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) because they do not buttress the Hindu-Us vs Muslim-Them image that the BJP wishes to enforce.

Significantly, the government of India aims to implement the Citizenship Amendment Act in tandem with a National Register of Citizens. The purpose of this is to eliminate all ‘illegal immigrants’ in the country. As per the Citizenship Rules, 2003, the central government is at liberty to issue an order to prepare the National Population Register (NPR) and create the NRC based on the data gathered in it. Interestingly, it was Census data collected from the state of Assam that was wielded by the ruling political party to generate a narrative of illegal immigrants ‘infiltrating’ India and robbing Indians of economic opportunities, that sparked off the CAA-NRC debacle in the first place.

Another strong point of contention in Census data is the issue of caste. It is primarily information collected through Census that is used to grant constitutional safeguards such as reservations in legislatures, government jobs and educational institutions. However, this has become a highly debated issue in contemporary times. There are many who consider this policy to be one that perpetuates the caste-system in India and argue for an altogether removal of caste-based data from the Census. There is yet another lobby that views caste-based reservation as being a step towards ‘Hinduisation’ of India and dilution of other religions in the country. Interestingly, however, the publication of caste-based data in the Census has been helpful in strengthening many political parties including the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and some other caste-based parties, which mainly articulate the interests of the Bahujans of India.

In 2021, the Government of India plans to carry out the decennial Census of India. It will be interesting to witness how the new census is implemented in the backdrop of such widespread dissent. More importantly, it remains to be seen how data collected through the Census will be used to formulate the proposed National Register of Citizens and the consequences it will have on secularism and democracy in India.

Gunjan Mitra is an undergraduate student pursuing B.A. (Hons.) in History from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi. She is a firm believer of nature conservation, more specifically marine conservation. She is a certified Divemaster from P.A.D.I. She enjoys travelling and photography and hopes to be able to explore the history, culture and languages of people from all over the world.