Kashmir prevails in different streams of an ethnic and a spiritual cosmos. It is an experience which is manifested through the hues of Chinar, the prayers and unceasing resilience of its people that have become one with the Dal Lake. The assimilative nature of the Kashmiri civilization has been essentially responsible for establishing the collective experience of ethnicities and cultural identities. The symbols of this assimilation exist in its linguistic realms, in the distinct fragrance of Kehwa and Sheer Chai, two most magnificent forms of tea, in the flavors of its traditional cuisine, in the traditional gowns – Pherans, to contest the harsh winters, the different kinds of breads of its traditional bakery – Kandur and it exists in several artistic virtues which reek of a rich history of literature that lives through every tongue and every conscience in Kashmir. It is where philosophies of Saivism, Sufism and Buddhism meet and attain consonance.

The idea of Kashmir resonates strongly through its traditional folk dances as well and it transcends into the serenades of Sufiyana music and the rhythms of Rabab, Sarangi and Santoor. One of the finest and most radiant traditional dances of the Valley is ‘Bacha Nagma’. The dancer is known as ‘Bacha’ – a young teenage boy and the song-dance proceeding is known as ‘Nagma’. It was initially only prevalent in the villages, prominent during the harvest season particularly as an expression for celebration. Eventually, it was integrated into wedding celebrations, religious ceremonies and festivals and now it has become an inseparable part of such significant processions. This dance form integrates the musical realms with the theatrical possibilities and consists of six to seven members. It provides the dancers and all of the accompanying artists on the musical instruments with a space to unveil, express and interpret ideas of love, spirituality, humor, and eroticism with utmost passion. The Afghans of Kabul had primarily introduced Bacha Nagma which was a reinterpretation of the traditional Hafiza Nagma folk dance grounded in Sufi roots. In ‘Bacha Nagma’ young male dancers dress up as women from the Hafiza dance, in order to make themselves look like women or rather submit to the structurally internalized cultural norms that constitute the very experience of a woman. Several academic and local theories have been put forth to explain and understand these occurrences. For the longest, the locals of the valley have believed that the this tradition of young boys dancing in an attire of a woman was prominent during the rule of Mughal emperor Akbar over Kashmir; in order to prevent them from disclosing their heroism and bravery, he persuaded the men residing in his palace to dress up like women. On the other hand, during the 1920s, when the ruling Dogra Maharaja came to power, Hafiz Nagma was officially banned as he believed the traditional dance was becoming too sensual and amoral; it contested the mainstream divinized representation of women on several levels.

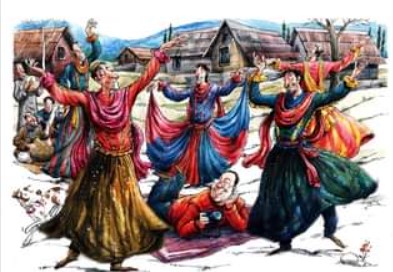

In Bacha Nagma, these young men dance and frolic around in long colorful skirts and dresses with ‘Dupatta’ or a veil which is a common symbolic determinant for women across cultures, draped around their heads. In order to elaborate and exhibit the persona of a woman further, they adorn their faces with make-up and wear jewelry. They’re swift on their feet and swirl unceasingly; gushing with several hues and tinted cheek bones. It defines elegance, beauty and a dignified form of expression in an unconventional manner which challenges the way we perceive beauty standards in our society. These aesthetic stylings of the body challenge the cultural norms of gender and sexuality. This dance form possesses several similarities to Kathak dance, as the attire of the dancer is quite similar to the traditional attire of Kathak; he indulges in quick spinning movements, pirouettes and a lot of emphasis is drawn towards the footwork as well. These movements get enunciated in a better fashion in accordance with certain facial expressions and gestures resembling that of a woman, which is of particular significance to Bacha Nagma and its audience.

This performance of a gender, the fictive experience as a woman is not looked upon as absurdity or chaotic. Rather, it is embraced by the audience, and by this virtue the audience reinforces the performance of the gender of a woman by men and rewards it too. This theatrical performance of gender can be analyzed through the post – modernist understanding of gender that all gender roles are cultural constructions which are performances being internalized by an individual rather than innate givens and which are then either upheld or refuted by society. This perspective enables the audience to witness the parody of gender roles and gender constraints imposed upon the body. For instance, the dancers of Bacha Nagma receive adequate training to develop flexible movements and gestures similar to the female dancers of Hafiza Nagma and are also taught to retain the sweetness in their voices. The actor’s anatomy enables the spectator to witness the difference between the natural and the constructed. Thus, the stage becomes a means of denaturalizing the system of gender binaries, encouraging the spectator to see gender as a representation and thereby dismantling it from within. These gender ‘performances’ reenact the concept of what it means to be a gendered male or female, and the gender identities are reinforced by adopting the stereotypical traits of femininity that denaturalizes the performance of femininity. This suggests that Bacha Nagma simultaneously denaturalizes gender while at the same time reinforces it. It mocks both the expressive gender system and the understanding of a true gender identity; undermining the experience of an authentic gender identity.

Theatrical conventions may constitute a safety net for the cross-dressers, since they disarm pre-conceived ideas of the audience and persuade them that what they witness on the stage is separate from reality. By contrast, Judith Butler- a significant gender theorist suggests that gender performances in non-theatrical contexts are governed by more clearly punitive and regulatory social conventions. On the street or in the bus, the ‘performative’ act becomes quite dangerous. Protected by such theatrical conventions, it opens up a space for cultural observation and contemplation that everyday performances can hardly achieve and is sustained by an implicit collective agreement.

Vrnda Dhar

Vrnda is doing her major in Sociology and a minor in Psychology from Lady Shri Ram College for Women and is a musician working with The Revisit Project, a Delhi based jazz/funk band. She's deeply passionate about the study of anthropology and ethnography and strongly believes in the significance of archetypes that constitute cultural realms, myths and mythologies as they determine the very reality of the society

I’ve been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thanks , I抣l try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your site?