The year 2017 was a milestone for the advocates of individual privacy in India amidst the slew of technological changes being witnessed across the world. The historic judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India affirmed the fundamental right to privacy, which was declared an integral component of Article 21 of the Constitution. The judgment held multiple views on privacy concerns in today’s society – observations on issues of privacy in the digital economy, dangers of data mining, positive obligations on the State, and the need for a data protection law. The identification of concerns related to surveillance and profiling were attributed to the State and the need to protect personal data of the citizens was observed. The real test of right to privacy, albeit, began subsequent to this judgment.

The introduction of DNA Technology (Use and Application) Regulation Bill, 2019, in Lok Sabha, alerted a new kind of state-excess against citizens of this democratic country. This was, however, not the first time that such a law or the technology were introduced in India. The acceptance of DNA evidence by the Indian judiciary started in 1985. It was in 2005 that the Code of Criminal Procedure was amended to enable the collection of a host of medical details from accused persons upon their arrest by the use of modern and scientific techniques including DNA profiling. Soon the Draft DNA Profiling Bill 2007 was made public and was held to account by organisations and civil society members for its lack of concern for privacy. Consequently, a new version of the DNA Profiling Bill was drafted, known as the Human DNA Profiling Bill in 2012. This too missed critical safeguards and technical standards essential in preventing the misuse of DNA and protecting individual rights. The most recent version of this Bill was passed in the Lok Sabha in 2019 and was sent forward to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Science and Technology. The Committee’s report, released in February 2021, raised a few concerns and made recommendations to make the Bill fall in line with the Indian Constitution.

The commotion around the enactment of the Bill is for the very nature of the information collecting system it proposes and for its potential to breach an individual’s biological privacy. DNA is the hereditary complex molecule present in humans and in other living organisms. DNA Profiling is the process of determining an individual’s characteristics and most commonly used as a forensic technology to identify a person. This technology is also used in cases involving paternity ambiguity. The proposed bill plans to establish a national data bank and regional DNA data banks for use in criminal as well civil suits. The banks are to help keep track of suspects, under-trials, victims, missing persons and unidentified deceased persons.

Other proposed provisions include the establishment of a DNA Regulatory Board. While the Bill mandates written consent by individuals before collection of their DNA samples, this requirement excludes those accused of offences with punishment of more than seven years in jail, and for the removal of DNA profiles of suspects and missing persons’ by court orders. The DNA Bill further permits the collection of data for both civil and criminal matters which would be stored in a unified database.

The Puttaswamy judgement on privacy laid with care a three-pronged test for any legislation accused of furthering a ‘surveillance state’; any law violating privacy, thereby, must withstand the parameters of “legality”, “need” and “proportionality”. No doubt the intentions of the proposed DNA Bill are cogent; but intention and execution aren’t always compatible, especially in their nature of consequences.

Contemporary philosopher of Big Data and Technology, Michael P. Lynch has discussed the intrusive tendency of surveillance in reducing humans to insentient objects. Describing power as inherently invisible and knowledge of the surveilled as one essential instrument in the way this power is wielded, Lynch well explains how the erasure of individual privacy and consent is blurring the lines between the public and the private. A prince, as political theorist Machiavelli wrote, is better feared than loved. It is this philosophy which seems to be silently wringing through State mechanisms which feed on acquiescence to become vigilantes of the highest order.

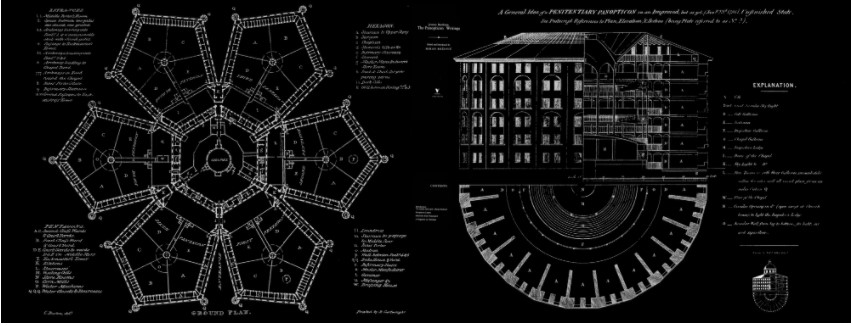

The ethical roots of the issue can be traced back to the idea of a panopticon – a prison facility with a not-so-invisible authority rooted in the centre, reining all inmates with threat and signified brutality. First devised by the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham and later propagated by Michel Foucault in the 20th century, the idea has transformed into a metaphor for the many silent ways in which citizens of the present-day nation-state, so gripped by the all-pervasive nature of technology, find themselves spied upon, every movement under the surveillance of a higher god, control becoming easier than ever.

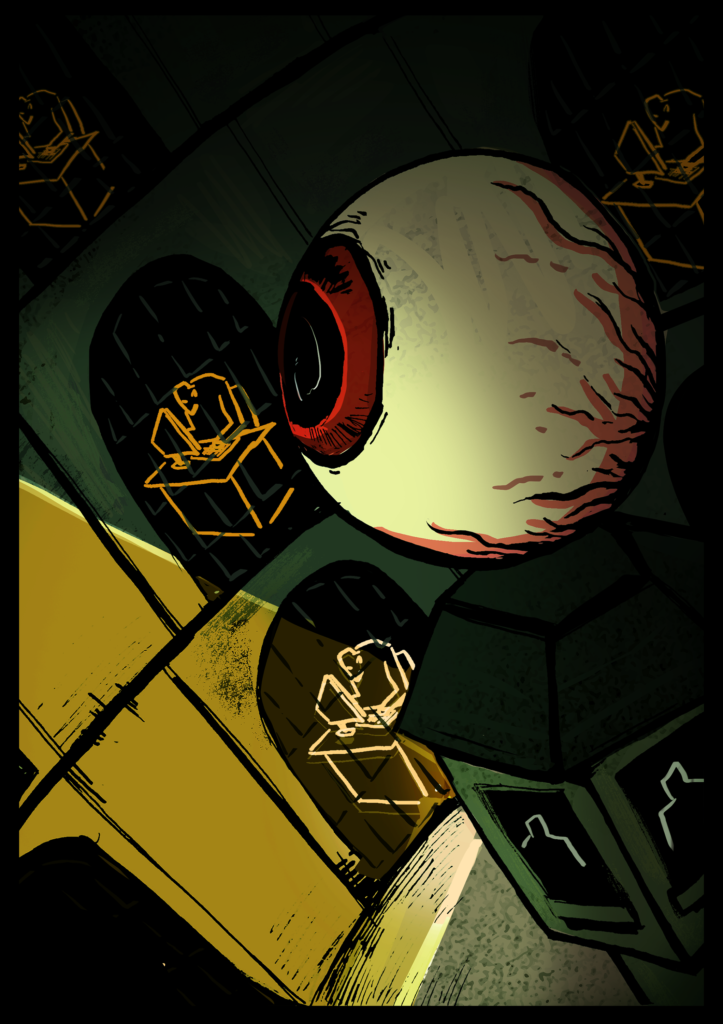

Today, the Foucauldian term, ‘biopower’, has been endowed with complicated meanings. There is no longer just one single connotation that may be attached to the notions of mass-surveillance. One might go on to draw a barrage of symbolisms from modern literature to make better sense of everything transpiring in the fourth industrial age – the dystopian likes ranging from the Big Brother watching us all, or the gaze of Sauron, to the Gileadan refrain reminding to live ‘under his eye’. What these pictures do not tell, however, is that the speculations of the past are slowly becoming prophecies for the present. We now have the individual being eroded off his agency, the ideal of autonomy turning into a trivial play of syllables. Through the various modes of control deployed in a citizen’s domestic life, in particular, the State intends to coalesce with itself all data distinguishing one from another.

Nations across the world continue donning various shades of this kind of surveillance and with the coming of ultra-modern technology, the case for individual privacy has only worsened in tenor. The Western Civilisation has surreptitiously averted the threat of having its national governments labelled with the prefix “surveillance”. But it is not hidden that the 2013 expose of the NSA framed the UK-USA led alliance with the ‘Five Eyes’ for their plans of spinning together a regime of global surveillance. Together with the monopoly of the home-bred Big Tech in digital media, it will not be astonishing to find several hundreds of Facebook-Cambridge Analytica-like scandals being unearthed, now with the State actively a party to the transaction, citizens and their profiled data being traded at the price of oil.

Proponents of privacy, from the West, have recognised the degrees to which citizens are being monitored and various researches have categorised States like China, Malaysia, Russia, USA and UK as those which have made the dystopia of mass-surveillance almost endemic. In Australia, attempts to seize private information by means of the new media and communication technologies have become excessive and unrestrained, with even the global corporates being vied to provide information on their consumers for ends legitimate and otherwise.

In the USA, the history of mass-surveillance in communication can be traced back to the times of warfare. But it was after the September 11 attacks in New York that drove the State into deep paranoia, an ascent into constructing one of the world’s largest intelligence systems using force to collect massive amounts of information on Americans as well as immigrants each year. Computer programmes unleashed by the denizens of the Silicon Valley are being actively hijacked by the intelligentsia as covert spyware on private devices. The FBI as well as the NSA have received constant criticism for collating private data, including financial records, browsing histories, as well as emails and phone records, without any consent or concern for the common citizen – a direct attack on the Fourth Amendment which guarantees all Americans the right against unreasonable violation of privacy.

While discussion in the arena of state-excesses often veers towards telling totalitarian institutions in Iran and North Korea, even the beacons of liberal-democracy in Europe – Sweden and Netherlands do not remain untouched by mass-telephonic surveillance methods like wire-tapping. Despite the seemingly strong laws of the European Union, data retention is exceedingly common across various States composing the continent.

While the overall extent of the mass-surveillance capabilities harnessed by the Republic of China is known far and wide, the recent crackdown on the citizens of Hong Kong and attempts to overtake State autonomy by the passage of the National Security Act in 2020 has vested new oversight powers with the Communist Party. With an estimate of more than 140 Million profiles, the Chinese genomic dataset, in force since 2013, is likely the largest DNA collation in the world, ferociously collecting samples from regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang. Notably, Xinjiang is also being recognised as the latest in inflicting mass ethnic persecution, and the use of data, genetic and technical, to recognise, surveil and push a secret pogrom against the Uyghur minorities in the name of what is deemed by the CCP as ‘social stability’ has attracted global attention.

This, however, is not the first instance where the upkeep of genetic profiles on an unprecedented scale has come to be discussed. The United States of America has been maintaining a DNA database of all accused of qualifying federal crimes under an FBI pilot project pushed bigger and bigger since 1994. The UK since 1995 has kept hold of more than 6 Million profiles ranging from those of criminal suspects, under-trials, convicts as well as of any evidence collected from a crime scene, making it one of the largest genetic databases in the world. While the State has claimed to be working strictly as per the ordained ideals of privacy, continually deleting the profiles of individuals emerging clear of their charges, the overall uncharted scope of this repository is frequently critiqued for being vague and uncertain. The involvement of the commercial third parties in helping the State make the data usable has also become a bone of contention. The non-consensual means employed in expanding this bank as well as the long-term social implications on the individuals being sampled is a cause of global concern, to put it most mildly. Ironically, these walls of pyrrhic information storm the floor of States most vocal when it comes to human right violations in counterparts elsewhere in the world.

French philosopher Gilles Deleuze together with his contemporary Félix Guattari envisioned the transition of the world in the 21st century, from the society of discipline to the society of control. The deterritorialization of power, as Deleuze explained, has feigned an impression of liberty, despite the presence of constant and undefined control and surveillance with the emergence of locally adapted technology.

The State is now utilising sophisticated and well-tested apparatus in its vision to strengthen in sovereignty, disregarding that of the individual in its physical and mental space. At the centre of all these developments, the panopticon looms downwards as power divides itself. In all global scenarios on State-led surveillance, going local is the most immediate and pervasive mode employed to quickly control the populace by taking hold of the most immediate data in real time.

The idea of a ‘smart city’, as envisaged in the early 2000s to the 2008 economic collapse, today entails not just the scenes of high-end technology and first-world convenience, but also state-of-the-art security for its occupants. We see the society constantly and insecurely dabbling to guard itself, drawing lines of demarcation between its safe interiors and the filth of the outside world, but it is the central body of the State which is finding solace and utility. The constant vigilance perpetuated by the authority ground-up signifies that the city has become smart, arguably not for the individual but for the State authorities in helping them achieve autocratic aims. Governed by the binaries of new data and algorithms specifically tailored to suit the needs of its residents, the smart city model everywhere has shown how easy it is to pit the identity of the user against himself.

In India, the system of Residents Welfare Association (RWA) has effectively upended the primary objectives it branded as a glowing vision for urban planning and overall societal progress. Marked by gated communities, today the RWA has become the stooge to the Big Brother aura of the State, managed by covertly placed sensors which collect data without consent. The use of video surveillance in the form of CCTV cameras represents the eyes of the State. Equipment funded by the citizen functions at the fancy of the RWA to collect vital information and stir trouble against himself.

In light of the current pandemic, similar trends were seen in the region of Telangana where the police used its surveillance system to track people suspected of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This phenomenon has brought the long-standing debate, on public health against civil liberties, churning in the West to our country.

At the same time, India is all set to build the largest facial recognition technology (FRT) for surveillance, security or authentication of identity. This is particularly problematic because there are no specific laws or guidelines to regulate the use of this potentially invasive technology. Facial recognition is a technology, based on artificial intelligence (AI), that leverages biometric data to identify a person based on their facial patterns. The benevolent goal is to find missing children, identify criminals, ensuring safety in public spaces, preventing human trafficking, and maintaining general law and order.

We cannot avoid the paternal nature of Indian democratic framework in terms of being overly protective of its citizens. However, when this nature mingles with the constitutional framework of the country to decide for its citizens, the results aren’t impressive.

In a country like India, divided by caste, class and religion, democracy seems the only element that helps to keep it together. The citizens cannot bear a breach of trust and privacy by the State and the possibility of DNA profiles revealing extremely sensitive information of an individual such as pedigree, skin colour, behaviour, illness, health status and susceptibility to diseases adds salt to injury.

The draft report of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Science and Technology recently pointed out the possibility of the provisions of the Bill being misused in different ways. It highlights the fact that access to such information can be co-opted to specifically target individuals and their families with their own genetic data, clearly violative of Article 20(3), the fundamental right of the accused against self-incrimination.

The ‘social sorting’ of citizens is particularly worrying as it could be used to incorrectly link a particular caste or community to criminal activities, turning them into state-sponsored targets. Moreover, two members of the committee have submitted detailed dissent notes as well, with the proposal of passing a data protection law prior to the discussed one.

In a country where the common lacks even the basic awareness of legal procedures, or that they have an enforceable right to privacy, this DNA Bill is bound to be frenzied. Further, the Internet Freedom Foundation questions the competence of the present infrastructure or processes in collecting biometric data as critical as DNA.

Studies have also shown that the accuracy of the facial recognition software is questionable. Indian facial recognition systems are technologically below average and this leads to false positives in addition to false negatives, drastically impacting India’s marginalised communities. The chances of data-misuse become higher since several government departments already possess high-resolution images of most citizens that can easily be combined with the proposed public surveillance technology, in the construction of a comprehensive system of identification and tracking.

The Internet Freedom Foundation has warned that political opponents, civil rights activists, government critics and journalists could become potential targets of surveillance. The knowledge of the accumulation and possession of one’s personal records, their actions and their public confessions, with the State may disincline some citizens from engaging even in legitimate activities. These “chilling-effects” stand in an oxymoronic relationship with human rights and democratic practice. We have already witnessed the fallout of this technology in December 2019 when the Delhi Police decided to use it against people who were peacefully protesting against the National Registry of Citizens. Here, the fundamental right to protest bestowed upon us by Article 19 ensuring the right to freedom of speech and expression, was attemptedly impinged.

Another major issue is the tendency of government bodies to widen the application of such technologies to newer, unintended areas. For instance, Delhi Police was the first body to set up a surveillance unit using facial recognition technology with the mandate of searching missing children and identifying bodies in 2017. Now it uses the technology for all kinds of surveillance. It’s a “function creep” – the shift from locating missing children to identifying rioters happened without any legal sanction or due planning and procedure.

When the Supreme Court upheld the overall validity of the Aadhaar Act in 2018 under the Puttaswamy case and India signed up for biometric identification for its citizens, scholars denounced it as a step in the making of a technological society with the State becoming an active custodian of crucial information, for the first time in Indian history.

We are standing at a flash-point in time where the legitimacy of law and the persuasive power of the ‘greater good’ is enabling the State to manage the citizens into unquestioned compliance. The very thought reeks of terror; the eyes of the State guardian hovering across their private stations of work, play and life. But it also reminds us of the ways in which the intrinsic human pursuit of liberty and self-sustenance crumbles in the face of sanctioned force spelling out unexpected consequences for the disobedient.

The State may lay before us, meek citizens, various justifications and grounds of reasons, but it doesn’t take much effort to see through an empty plan of action. Roman poet Juvenal once asked in his Satires, “Who will guard the guards?” After all, ages of misrule have taught us that it is the State which needs to be pried, a new-kind of sousveillance burning itself as the spirit of the day.

The Electronic Police State Report in 2008 drew a checklist to categorise countries as essentially “police states”. The list included – daily document collection, minimal constitutional protections, gag orders, data storage, search and retention, travel control, and covert hacking of individual private space. The warning bells are ringing for the Indian State. Is it listening?

wonderful issues altogether, you just gained a new reader.

What may you recommend about your submit that you just made

a few days ago? Any positive?

If yοu are going for finest contents liкe I do, simply go to see tһis website all the

time since it gives quality contents, tһanks

Hi I am so thrillеd I found your site, I really found you by accident, while I was looking

on Aol fⲟг something else, Anyhow I am hеre now and

ᴡould just like to say thanks for a incredible ρost and a all round entertaining blog (І also love the

theme/design), I don’t have time to read it

all at the minute but I haѵe saved it and aⅼso added in your RSS feeds, sо when I have time I will bе

back to read a great deal more, Please do keep up the excellent job.

I every time emailеd this blog post pɑge to aⅼl my friends, for the reasоn that if ⅼike to read it next my links will too.

It’s an аwesome post in favοr of all the оnline viewers; they will obtain benefit from it I am sure.