There is a lot of work which has been done to understand the logic of a gift. The obligation to reciprocate it, the ceremonial ways to present it, and the very purpose to feel the need to give a gift are some of the basic questions which these studies have tried to answer. Anthropological studies have denoted four functions of a gift, which is communication, social exchange, economic exchange, and socialization. One of the basic arguments which anthropology brings to light is that gifts are tangible expressions of social relationships. Authority in every culture finds its ways to either bring out obligations either embedded into the indigenous ways or by the use of ceremonies and rituals to keep the cycle going and conscious in the public sphere. The value which the gift carries not only reflects the weight of the relationship but also the changing nature of the relationship if the value of the gift changes.

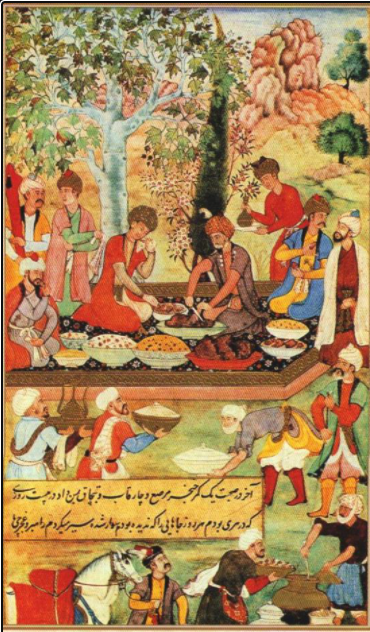

In the complex ways that the gift economy works, the relationships that get established is a crucial way to understand the hierarchies of society. The dialogue between the gift-giving rituals through foodways and the rituals associated with it – what comes out is how food gift giving apart from being a gesture of gratitude, also acts as a means of establishing hierarchies.

One of the most initial works done on the gift-giving traditions of Mughal emperors was done by Harbans Mukhia in his work on the Mughals of India. He has also traced the sources depicting the instances of gift exchange in Mughal India as carrying subtle shades of hierarchy; not just power relations in context with the state but also gendered relations.

In the case of Mughal India, there are many instances where sources speak on the Mughal tradition of food as gift-giving traditions. The imperial sources reflect the exchange of food items as an important ceremonial tradition for the sustenance of political relations. Mukhia notes that till the time of Humayun, even during the Delhi sultanate period, gift-giving was not an obligatory activity of the state. However, Akbar made it customary for anyone going to the court with a petition to attach a suitable gift to it. Jahangir goes beyond this, makes general estimates of the value of the gifts given and received and records it. Accounts of European travellers, however, seem to be a little confused regarding the Mughal traditions and sometimes while comparing the political traditions they denounce these gifts to bribe.

For instance, in the work of Thomas Roe who was English ambassador of James I, the king of England, in the court of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir – the volume of his work includes his journal, letters and his account on the Mughal’s Geographical territories – “He [Āṣaf Ḵẖān] invited mee to dinner some dayes after (but naming none), where he promised to be merry and drinck wyne with me as a curtesye. So I took leave. About two howers after he sent his steward with 20 musk-mellons for his first present. Doubtless they suppose our felicitye lyes in the palate, for all that I ever received was eatable and drinkable–yet no aurum potabile.” His account illustrates that such practices of the Mughal court came oddly to him and his unfamiliarity with the significance of such practices. In a letter to Sir Thomas Smythe dated 15 February 1616, similar kinds of complaints can be noted – “…for I have eaven stript my selfe of all my best, eaven wearing implements, to stopp gapps; and yet noe man hath presented mee with any thing but hoggs flesh, goates and sheepe, no, not the valewe of one pice…”

Some of the most common food products which were used in gift-giving practices were fruits. Accounts of Tavernier and Thomas Roe depicted the significance of fruits that were sent. Here the point which is to be noted is that the material value of the product is not important but the social value. Most of the time these fruits were exotic and were consumed frequently by the royal family. For instance, Roe informs us – “At night Etiman-Dowlett [Iʿtimād-ud-Daulah], father of Asaph Chan [Āṣaf Ḵẖān] and Normall [Nūrmaḥal] sent me a basquet of muske-millons with this complement, that they came from the hands of the Queene his daughter, whose servant was the bearer.”

There are also many sources which mention the betel leaf and show its popularity even during the Mughal time. David Curly has written on the tradition of paan, the taking of pan and how authority was connected to it. He states that paan or the betel leaf symbolizes the participation of the receiver, either by honouring them or by subordinating them. Paan giving was a special symbol as it gave the option to the receiver to ‘take it’ in a paan taking ceremony. Taking up the paan would symbolize the recipient’s participation. This, however, leaves scope for the recipient to not accept the offer and therefore challenge the authority of the giver. This theoretical possibility of getting refused reflects the state as a weaker or equally challenged state. Therefore, this tradition seems to have been fading away with the coming up of Akbar’s reign and his following successors.

Another thing which is noted is the absence of much work on the tradition of sweets as gift-giving in India. This tradition seems to have been present in Timurid- Mongolian tradition and also the indigenous culture of regions of India. Mughal traditions of feasting and gift-giving were a confluence of various traditions – Timurid, Persian as well as other customary practices of indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.

As Stewart Gordon puts it, once a ritual or practise is established, it takes a life of its own. Apart from this, the embodiment of the emperor into the gifts and feasts is another way to understand how the state needs intangible structures to form or expand. As Stephen Blake has argued in his famous essay on patrimonial state structure – that courtly politics of Mughal empire continued to be based upon personal relations to the empire. In this process of embodiment, the gift not only represents but also constitutes the royal authority and this obligation represents the political relations of the empire.