It is a common sight for people residing in urban centres to see and interact with people who have come from elsewhere. The said group includes people from both formal and informal sectors, with the latter employing a significant majority. In the wake of discussions on urbanisation within the larger context of informal economy, an important aspect which deserves greater attention is the provision of decent living environment to migrant workers.

It is a common sight for people residing in urban centres to see and interact with people who have come from elsewhere. The said group includes people from both formal and informal sectors, with the latter employing a significant majority. In the wake of discussions on urbanisation within the larger context of informal economy, an important aspect which deserves greater attention is the provision of decent living environment to migrant workers.

The Indian Constitution under Article 19 gives its citizens freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business. If one were to stretch this logically, inter alia, one can safely say that it is the State’s responsibility to facilitate internal migration (migration within India).

In this light, we attempt to map the scenario of internal migration in India today and make brief observations on a few basic provisions to which every citizen is entitled.

A Snapshot of the Scenario

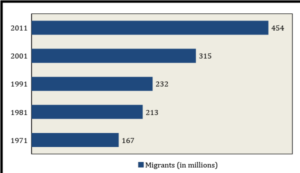

In India, internal migration accounts for a large population of 454 million, as per Census of India 2011, nearly 37.5 per cent of the total population. Internal migrants, of whom 71.5 per cent are women, are often excluded. Migration has been the main component of mass urbanization. India’s urban population has increased from about 286 million in 2001 to 377 million in 2011 and is expected to increase to 600 million by 2030. For the first time since Independence, urban population growth (91 million) has exceeded rural population growth (90.5 million) within the last decade (from 2001 to 2011). The inter-state migrants in the country could be summed up to 55 million i.e. roughly 5-6 million individuals a year between the years 2001 and 2011. This went up to 9 million per year between 2011 and 2016. These inter-state migrants who are in the age group of 20-29 years constitute 20% of all migrants.

Internal Migrants, 1971-2011

Internal Migration is primarily of two types

- Long-term migration, resulting in the relocation of an individual or household

- Short-term or seasonal/circular migration, involving back and forth movement between a source and destination

Long-term migration contains an element of stability where the migrants generally have the time to settle down and do not live as precariously as short-term migrants. Estimates of short-term migrants vary from 15 million to 100 million as per NSSO 2007-08 data. Furthermore, seasonal migration is widespread, especially among the socio-economically deprived groups, such as the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Castes (OBCs), who are asset-poor and face resource and livelihood shortfalls.

It is vital that one sees the following concerns in the context of the socio-economic condition of short-term migrants.

Documentation and Identity

22% of internal migrants are considered to be seasonal migrants or migrated for short tenures if one were to go by the maximum number of 100 million quoted above. This number is almost equal to the current population of the state of Bihar (2018). While socio-cultural integration is a process that takes its own time, regulations and administrative procedures make things worse for migrants. In most cases, they exclude migrants from access to legal rights, public services and the promise of social and economic welfare schemes accorded by the State to the residents, on account of which they are often treated as second-class citizens.

For instance, a prerequisite to open a Jan Dhan bank account was to provide proofs of identity and address. Seasonal migrants have faced problems, as some did not have proof of their local address. So in spite of having an Aadhaar card or a Ration card (which is not considered as proof at a few places), they were not eligible to open an account.

Political Exclusion

Casting a vote is not only a prerequisite for a vibrant and substantive democracy, but also reaffirms public faith in citizenship and the supremacy of any governing body Elections serve as that opportunity where people choose their representatives, who will, in turn, voice their concerns. In this context, the State should strive towards including as many citizens as possible in the voting process. The inability of seasonal migrants to exercise this right should be addressed and the State should play a facilitative role in helping them cast their vote. If nothing else, the sheer number of people in question validates the need to include them in the electoral process.

Housing

Labour demand in cities and the resulting rural-to-urban migration is causing greater pressure to accommodate more people in urban areas. In 2011, 68 million Indians lived in slums. This number is equivalent to one-quarter of the population of India’s 19 cities, with more than 1 million residents. Most migrants end up sharing squatted space in slums and an even larger number are denied even that. Unaffordable rents in slums force them to live at their unorganized workplaces (such as construction sites), on pavements, or in open areas in the city. This further magnifies their vulnerability to harassment by the police and other local authorities. Moreover, the local government neither provides adequate rehabilitation for slum dwellers nor low-cost housing for the urban poor.

It is observed that seasonal/rural-urban migrants generally take up construction work, where accidents and deaths are extremely common. Construction work is just one example of the many low-paying and unskilled jobs that seasonal migrant workers take up. Owing to such jobs being regarded as casual labour, employers rarely provide for their employees’ social security. In such a situation, it is the duty of the State to ensure that the people engaged in such work are taken care of. Furthermore, access to goods provided through Public Distribution System (PDS) should be made available to migrant workers. A Code on Social Security and Welfare (March 2017) and a Labour Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (March 2018) were announced by the government. However, not much has been done in this regard in the past two years. The government has claimed to pursue them this year.

It is observed that seasonal/rural-urban migrants generally take up construction work, where accidents and deaths are extremely common. Construction work is just one example of the many low-paying and unskilled jobs that seasonal migrant workers take up. Owing to such jobs being regarded as casual labour, employers rarely provide for their employees’ social security. In such a situation, it is the duty of the State to ensure that the people engaged in such work are taken care of. Furthermore, access to goods provided through Public Distribution System (PDS) should be made available to migrant workers. A Code on Social Security and Welfare (March 2017) and a Labour Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (March 2018) were announced by the government. However, not much has been done in this regard in the past two years. The government has claimed to pursue them this year.

Conclusion

The intensity of migration is expected to increase in the future as a response to economic crises, political currents and global changes. A few experts opine that internal migration is an integral part of the development of the country. The rising contribution of cities to India’s GDP would not be possible without migration and migrant workers. Additionally, migration is believed to provide an opportunity to escape caste divisions and restrictive social norms and enables the migrant to work with dignity and freedom. At this juncture, there is an urgent need to develop a governance system for internal migration in India, i.e., a dedicated system of institutions, legal frameworks, mechanisms and practices aimed at facilitating internal migration and protecting migrants.

Author: Alankrita and Vignesh (krvigneshkarthik@gmail.com). They are policy analysts based in Delhi.