In light of this, it is vital to gauge the passage of the indoctrination of English into our milieu, which can be done by tracing the history of Indian English Writing. When the British first arrived in India, they found a diverse and dispersed subcontinent coloured by differences on the basis of caste, language, geography, culture, customs, and importantly, religion. The ‘civilising mission’ of the colonisers worked in tandem with the biased opinion that they had of the native Indian—of being orthodox, ignorant, and archaic in their way of life. The colonised were brainwashed into believing the same, which in turn helped the colonists to impose their doctrines of hierarchies.

Thus, began the first phase of the history of Indian Writing in English. During the Bengal Renaissance (1830-1850), the middle class society, especially in Bengal, found themselves in awe of the ideal of the “civilised” way of life that the coloniser presented them with. They were made weary by, as Professor Anand Prakash puts it, “rituals, dogmas and the overarching caste divisions” as well as “the baggage of old knowledge contained in India’s ancient and medieval texts.” However, it has to be maintained that the groundwork for the aforementioned indoctrination began in the eighteenth century itself as a step towards the colonisation of India. As Arvind Krishna Mehrotra writes, “the introduction of English into the complex, hierarchical language system of India…proved the most enduring aspect of this domination.”

This first phase was coloured by experimentation in various forms of literary writing, an introduction to the apparent “superior” literatures of Europe, social reforms, and “modern” western forms of education and perspectives presented by the coloniser. These new paradigms seemed exciting and challenging at the same time. It was acknowledged that the English that would emerge would be alien not only to its roots back in England, but alien to its place of its birth in the Indian context, too. This “new English” would not be able to embrace and incorporate the nuances that the Indian languages and its milieux presented.

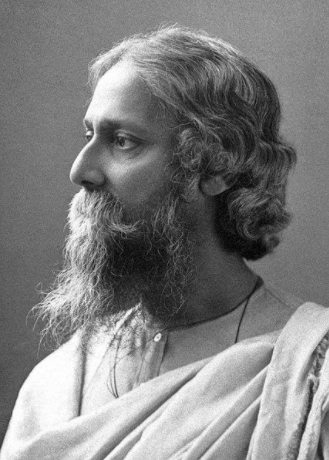

Nonetheless, there was another school of people who refuted this biased Western thought process of Indian culture being diminished, viewing it as orthodox and ignorant. It was implied that the medieval period in India (approximately 13th-16th century) was devoid of any growth or development of any form. This brought about a need for an awakening, which propagated that Indian culture, as K.S. Ramamurti writes, “was not the culture of blind faith and superstition but a composite one which, though complex and heterogeneous, had in it strong scientific, technological and rationalistic components, along with intellectual, aesthetic and spiritual components.” Writers like Rabindranath Tagore, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Balgangadhar Tilak, Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya, Toru Dutt, among others, took it upon themselves to promulgate the aforementioned gap between ancient India and the nineteenth century, thereby filling the lacunae formed by the misunderstanding that the medieval period was a stagnant period for India. Tagore and Bankim Chandra were bilingual in their approach. Translations from English texts to Indian languages and vice versa also brought about a fluidity between cultures, which was originally not sought.

The twentieth century brought along feelings of discontent and resentment towards the colonisers—there was now an awareness of the reality of excessive exploitation, and the brutal, violent wiping out of a sense of origin. It is noteworthy that during this period of rising national sentiment—evidently the second phase—English language took a back seat, and the Indian languages gained prominence in the propagation of nationalist fervour and political agendas, writings, and campaigns, especially in the grassroot levels.

This period saw literary works in Indian languages dealing with, as Prakash puts it, “emancipation from the foreign rule (Mulk Raj Anand), the need of new fervour and passion across villages and towns (Raja Rao), and the persistence of a critical attitude toward entrenched prejudices, irrational beliefs among India’s masses (R.K. Narayan).” This inspired the English Indian writers also to adopt similar themes in their writings. Prominent works of Tagore, K.M. Munshi, and Rajagopalachari alternated between politics and writing. There was a spurt in the production of Indian language literatures, too, like Bengali, Marathi, Tamil, Malayalam literatures, and also literatures in the North, like Punjabi and Gujarati, creating a sense of a united front where a unified identity was established and propagated.

The third phase post-independence saw Indian English disassociate from the legacy that the British had left behind. The themes of this time examined decolonisation, self-reflection, and adjusting—not only on an emotional level, but also, as Gangadhar Gadgil terms, on “intellectual and ethical-philosophical planes”. In the second half of the 20th century, English found eminence in public school education, where it trumped all other Indian languages, and started to be widely accepted and integrated. The generations during this era had no remembrance of the experience of colonisation and only sought self-development and aggrandisement.

Ultimately, in the 1970s, we saw the adoption of English for official use throughout the nation and the rise of the privilege that came with it as it became a language that was not accessible to all. Thus emerged the Indian English language as we know it today. As Prakash, paraphrasing Mulk Raj Anand, writes, “English is no more what the British meant it to be, but has become Indian in its many local ‘vulgar’ forms that it has attained in the country.” The translations of various, otherwise non-accessible forms of literature into English has indeed helped in reconnecting with ancient oral traditions, folklores, myths, and legends, which are aspects of Indian culture that present generations are not familiar with. Today, Indian English is spoken as any other Indian language in major parts of our country. Nevertheless, debates and discussions till date transpire over the adoption of the “coloniser’s language”.

It also has to be conceded that in the process of trying to define what Indian English writing constitutes, which includes translations of works of Indian languages, major works of Indian language do not gain any recognition. They are not translated, or if they are, they lose their authenticity in translation. Due to the decreasing readership of works of regional languages, these languages face the peril of extinction in a few decades. Surprisingly, regional languages seem to be in danger, not by the hands of English, but as Salman Rushdie argues, “with the effects of the hegemony of Hindi on the literatures of other Indian languages, particularly other North Indian languages.” Therefore, it is paramount that the dynamic of Indian literatures should be in a continuous flux and should acknowledge, appreciate, adopt, and celebrate the myriad tongues, heritages, and cultures it presents with, in order to keep it alive and thriving.

Smriti has done her BA in Literature from Hindu College, Delhi University and MA in Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia University. She is also an Alumna of SBI Youth for India Fellowship.

In a room of her own, you will often find Smriti speak to spectral masked vigilantes who save the world of mortals during nocturnal hours. As a sensorial hybrid, she believes in the sight of bright colours, sound of mountain rivers, loving touch of jumping puppies, and fragrance of old books. Smriti aspires to work as a teaching faculty to create a dialogic classroom space with vibrant discussions.