“At about 12.30 am, I woke to the sound of Ruby coughing badly. The room was not dark, there was a street light nearby. In the half light I saw that the room was filled with a white cloud…. They were yelling ‘bhaago, bhaago’ (run, run), our eyes were burning. My mother-in-law, who was also coughing badly, came into the room……The family were coughing and groaning. We tried closing all the doors and windows to stop more gas from coming in, but the room was already full of white clouds”

– Aziza Sultan, Bhopal Tragedy, 1984.

(Source:bhopal.net)

“Another survivor said he and other family members sensed pungent (sic) smell and they could even see the fumes. “We felt uneasy and started vomiting. We don’t know what happened after that but later found ourselves in hospital,” he said.

People ran helter-skelter after the leakage………People in at least five villages near the plant were worst affected. Many fell unconscious on the roads or had breathing problems.”

– Visakhapatnam gas leak, Hindustan Times, May 7, 2020.

These extracts, remarkably similar, are set apart by almost three decades. The first extract is from an account by a woman who survived the methyl isocyanate gas leak from a Union Carbide India Limited pesticide plant in Bhopal in December, 1984, while the second account is a small extract from a newspaper report a day after the leak of styrene from a chemical plant in Visakhapatnam in May, 2020. Both incidents involved leakage of toxic fumes from chemical plants, leading to a number of deaths and also leading to long-term health issues in otherwise healthy people. The question of whether any change took place in these three decades becomes significant here. This article attempts to try and understand the trends of changes and changelessness in these last 30 years.

On the night of December 2, 1984, the world’s worst industrial disaster graced us with its presence – more than five lakh people were exposed to poisonous gasses, such as methyl isocyanate in Bhopal as a consequence of the leakage from the pesticide plant, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL). Following this night, the tragedy caused burning sensations in the eyes and lungs of hundreds of people in the city. It further led to different kinds of deformities in women and children for generations to come.

The Bhopal incident remains an unceasing part of the global environmental tragedy, disregarded by hegemonic powers and reigns and it prevails in the same light as that of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki incidents. The lives that were lost have etched further into the wounded collective morality, sustaining stains that were not meant to be forgotten, but resolved. The Union Carbide plant was set up in 1969, under the facade of the effort to bring about Green Revolution prosperity through high yield agriculture that was dependent on heavy inputs of chemical fertilizers and pesticides and the communities exposed to the leak of methyl isocyanate, comprised of slum – dwellers who had no legal voice after migrating from villages where the very phenomenon of Green Revolution agriculture had taken away their land. In essence, it was a colonial settler project that primarily aspired to outsource and exhaust resources and exploit wage labour. The plant was located in an already densely populated area despite city planning codes which require facilities handling hazardous substances to be located away from human settlements. Additionally, the plant was not designed to fully accommodate safety precautions. The most affected colonies were among the poorest in Bhopal. Many slums and shanty towns crowded close to the hazardous industry because this was the land that no one wanted to possess. This selective utilization of urban landscapes unearths the fact that the lives of the downtrodden and underprivileged can be dehumanized and dismissed conveniently for the sake of capital and greater profits, governed by the bureaucratic control over the history of the disaster. The impact of any disaster, natural or industrial, is also felt more acutely by the disadvantaged sections of society, especially women.

The relationship between the industrialists and the workers also seemed to have influenced the nature of such environmental hazards and risks. Poor working conditions had left several workers agitated, who had been constantly expressing their need for better policies and a better infrastructure. In a Marxist understanding, the sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of the society, on the basis of which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. This unceasing Taylorism of the collective consciousness of the working class is what reinforces the existence of social gulf between the bourgeois and the proletariat, furthering the dehumanization of the latter.

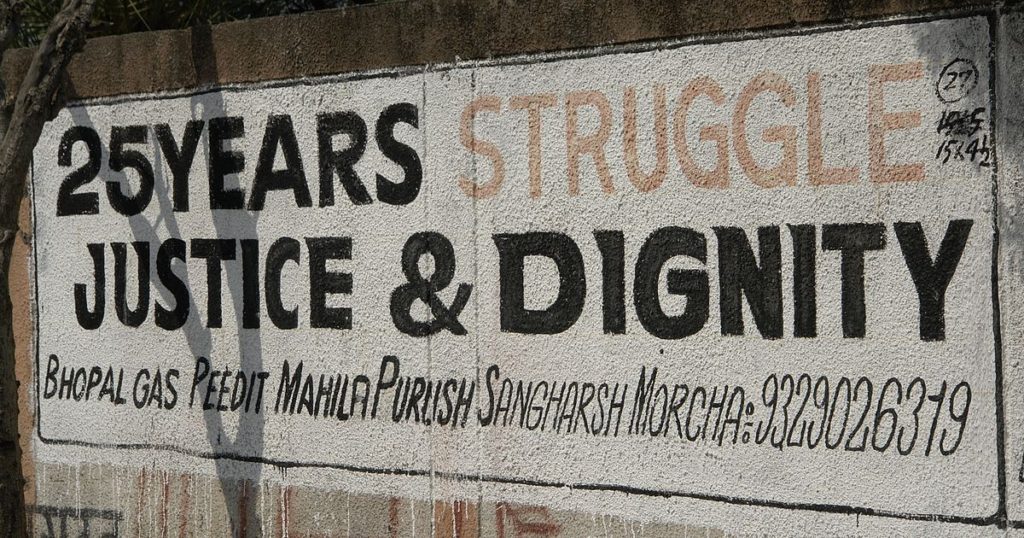

It has been nearly thirty six years since the Bhopal gas tragedy took place and justice hasn’t yet prevailed for the victims in any capacity – their voices, their realities have rather been brutally done away with, by the bureaucratic political actors. The industrialists, the government and the medical community – the bureaucratic trinity, haven’t admitted to any kind of accountability whatsoever and actualized promises that were made to several victims, rather they have tokenized and ‘capitalized’ the experiences of these victims for several other ‘development endeavors’. In such an understanding, the industrialists and the government become a part of a continuum that stands in an antagonistic relationship with the working class and the poor who inhabit spaces around the industries, who cease to transcend these spaces for good, rather they’re furthered into a displaced existence. Further, we see that there have been numerous small scale incidents of similar nature which shows that though there has been a semblance of change, a lot of it has remained on paper or such change has been structured in a manner that it continued to uphold the status quo.

Laws, rules and judicial interventions

Post the Bhopal tragedy,there has been an expansion of the legal framework to prevent these cases as well as to ensure restitution to the victims. During the Bhopal gas leak case, the accused were charged under very lenient sections of the IPC, considering the magnitude of their crime. Initially, they were charged by the CBI under Section 304 of the IPC, which deals with culpable homicide not amounting to murder, warranting a maximum punishment of ten years. However, the charge was later watered down by the Supreme Court in 1996, with the accused being charged under Section 304A, involving death by negligence and warranting a punishment of not more than two years.

Soon after the tragedy, the Bhopal Gas Leak (Possession of Claims) Act was passed in 1985, which allowed the Central Government to secure claims arising out of the tragedy to the benefit of the victims. The Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991 provided for insurance to claim relief in accidents while dealing with hazardous substances.

As environmental concerns slowly began to be given greater importance in policy making both at the global and local level, the Environment Protection Act, 1986 was passed, which not only sought to promote the reduction of pollutants, but also sought to protect people from any action detrimental to the environment.

Over the years, as environment related cases have gone up, the government set up separate quasi-judicial bodies like the National Environment Appellate Authority (1997) which dealt with environmental questions pertaining to industries, and the National Green Tribunal in 2010, which covered a wider range of environmental issues, mostly pertaining to protection and conservation of forests.

However, these bodies which were set up were quasi-judicial in nature, and hence they lack some powers which a lot of judicial bodies have; the first and foremost being that the NGT is a statutory body, and not a constitutional one.Further, the NGT faces funding shortage, lack of manpower, inability to enforce decisions as the decisions are often challenged in the higher courts and a lack of statutory regulations which gives the NGTs the power to enforce decisions.It has been accused of rarely going against the interests of the government, thus in effect, such bodies have been allowed little independence to function. For instance, in spite of the safety threats that a Sterlite copper smelting plant in Thoothukudi posed to the people there owing to gas leaks which killed a person and affected several others in 2013, the NGT struck down the decision of the Tamil Nadu government to close down the plant.

A slew of rules and statutes lay out the framework within which the chemical industries are expected to operate, laying out in details, the rules of procedure with respect to handling hazardous substances, as well as how to proceed should a disaster strike. These also stipulate regular inspections and auditing by government appointed inspectors. Some of these rules include the Manufacture, Storage and Import of Hazardous Chemicals Rules, 1989, Rules on Emergency Planning, Preparedness and Response for Chemical Accidents, Major Accident Hazard Control Rules, 1997.

The leakage of oleum gas from a unit of Shriram Foods and Fertilisers that led to several being hospitalised in Delhi led to the landmark MC Mehta v. Shriram Foods and Fertilisers case,(1986) where the Supreme Court invoked the doctrine of strict liability for enterprises engaging in hazardous activities which can cause a potential threat to those in the vicinity, by making them responsible for upholding top-notch safety practices for the protection of those working within the unit as well as those living nearby, and that these people are entitled to a compensation due to any harm caused by such potentially hazardous activities. However, the strict liability also had a loophole in the sense that, in case there was an inadvertent harm caused in spite of all precautions taken by the enterprise,they may be excused, if the harm caused was shown to be inadvertent or an Act of God. Hence, in this case, the Court went a step ahead and invoked the doctrine of absolute liability, making the enterprise liable for any harm, irrespective of whether all safety standards have been maintained or not- in absolute liability, “mistake of fact” cannot be a defense. The only exceptions include, mistakes occurring due to the plaintiff’s consent or mistake, the harm caused by natural disasters/acts or if the action needed to be executed under statutory law. Moreover, the Supreme Court expanded the ambit of Public Interest Litigation in this case, making justice accessible to the affected groups. Even after invoking these path-breaking judgments, negligence of safety standards and ‘inadvertent errors’ have continued which have put several lives in jeopardy.

The government has proposed a new set of rules, called the Chemicals (Management and Safety) Rules, currently in the drafting stage and not yet formalised into rules. A notification, registration, and restriction approach has been adopted, whereby notification and registration is required for all substances listed manufactured, imported, and/or placed in Indian Territory “in quantities greater than 1 tonne per annum … within one and half years from the date of inclusion of the substance in Schedule VI (of the draft).” Therefore, there have been numerous efforts to regulate the working of the chemical industry in India with focus on safety and security post the Bhopal tragedy

Corporate greed and state power-an unholy alliance

However, merely codifying laws and rules cannot be seen as enough unless there has been willingness on part of the state to implement them and to bring the violators to book. There is considerable laxity on the part of the state in enforcing such rules, as seen in the Bhopal case as well as in the more recent tragedy in Visakhapatnam. The state, in many cases, is found to be in connivance with the offenders, and undertakes little effort to charge them.

In the Bhopal tragedy, the government of India was accused of abetting the escape of the chief of the Union Carbide, Warren Anderson, who eventually did not stand trial in the case. The government of India made attempts to extradite him from the US, but failed in that endeavour as well, as the US government refused extradition.

However, as the scholar C.Sathyamala has pointed out, the case of Bhopal “is not that of corporate crime alone but that of the nexus between national governments and transnational corporations, of state and capital…” This connivance between the Union Carbide Corporation and the government allegedly went back a long way–the government of India is believed to have issued the industrial license to the UCC in spite of warnings by its own officials in the Ministry of Industries regarding the usage of outdated technology, which could be potentially hazardous (in this case, this turned out to be so). Even the the Bhopal Gas Leak (Possession of Claims) Act , 1985 was seen as an attempt to shortchange the victims as the Act denied the victims’ right to approach the court or appoint lawyers at their own volition-and in turn dilute their case, and secure a compensation amount which was not enough. In the end, this is exactly what happened–the government and Union Carbide settled the suit for $ 470 million, against an earlier demand of $4.4 billion as compensation.

Moreover, investigations have shown that the gas leak was not a sudden, out-of-the blue incident, the officials were not only aware of the manufacturing defects of the plant, but also there is considerable evidence that there was considerable lapses in security and maintenance of the plant and cost-cutting on part of the authorities in this regard.

Even during the Visakhapatnam tragedy, it emerged that the offending corporation, LG Polymers did not have the required environmental clearances, and undertook illegal expansion of the unit’s capacity, even though the Andhra Pradesh government did not allow expansion. Similarly, in the Thoothukudi case, as pointed out earlier, the Tamil Nadu government ordered the closure of the Sterlite plant, but the NGT overturned its decision. Therefore, in most cases, it is evident that the industries continued to operate even in the absence of requisite clearances, pointing to the failure of the government to crack the whip on the errant industries.

Social Justice and Community Health

It has been often seen that the government has attempted at controlling the situation, rather than looking for a sustainable remedy in Bhopal and Visakhapatnam. According to several activists, the medical files of the individuals impacted were not structured for a diagnostic analysis but for easy categorization of the victims. Despite mass indicators of widespread and increasing morbidity, official categorization only placed thirty thousand individuals within compensatable categories in Bhopal. The Gas Relief program initiated by the government for those who constituted the ‘gas victim community’, the community hospital and private doctors were committed to deciphering and organizing ‘real victims’ and ‘fake victims’. On several occasions, it was conveyed that the disbursement would be allotted according to the medical categorization of this data provided by the Madhya Pradesh government which was in reality not based on sufficient diagnosis and laboratory tests. As a consequence, the results remain unrepresentative of the severity of the injury among the gas victims. This stems from ambiguity surrounding many of the symptoms of the gas and from resistance to the idea that if the consequences of the gas persist, gas relief doctors may have failed to cure them. The attitudes of gas relief doctors also relate to inequality, as well as to ideas about class, caste, and poverty that inflect and complicate notions of legitimate illness representatives, as caused by poverty and preexisting conditions. Till date, the symptoms of ailments in gas victims are dismissed greatly based on a notion that gas victims are no longer as poor as they were before, and therefore not legitimate recipients of the charity of gas relief system. In such an understanding, rehabilitation and the connotations that it carries cannot be identified as expressions of individual freedom from disease to be brought about by disbursement of cash and antacids. The situation in Bhopal makes it clear that health is not solely a medical terminology, rather it requires major reorganizations of the social structures to provide communities some control over a range of life support systems, which eventually defines one’s accessibility to certain significant life chances. In a research study by Bridget Hanna, she discusses how the bureaucratization of the Gas Relief system in Bhopal led to the furthering of injustice and, deep – rooted institutionalized silence. Eventually, the gas relief system failed to validate the injuries that were gas inflicted, and it opened up a larger market for private practitioners who offered the same treatment for profit, but with a different attitude. Instead of getting “relief” from their exposure, the gas affected became the centerpiece of a greater medical industry that profited from their illness, even as it was constantly suspicious of it.

The gas victims were not only subjected to biological, ecological and economic disadvantages, but also to a grave psychological and social trauma. Several of the families affected suffer from post – traumatic stress disorder, till date. These experiences are prominent in both Bhopal and Visakhapatnam, prevailing in parallel realities and cut from the same cloth – corporate misadventures and institutionalized apathy. In times like these it is the collective resilience of individuals that enables one to contest the state sanctioned exploitation on numerous levels. For instance, protests broke out in Thoothukudi in Tamil Nadu in 2018 over the expansion of capacity of the Sterlite copper smelting plant there. The plant posed a great healthcare hazard for the local people, for it was a source of sulphur dioxide pollution in the air- numerous leaks had been reported from the site over the years. Thus, the plan of expansion was met with severe resistance by the common people, bringing the issue to national focus, with political and other activists joining in, which eventually led to the closure of the plant, and the air quality of Thoothukudi is believed to have improved considerably.

The Thoothukudi protests and several other protests serve as a testimony to the efforts of the people to reclaim their spaces and as well as a reminder that despite certain constraints like the greed of corporate forces, and the state’s tacit and at times, open support to it, it is indeed social mobilisation which can actually bring about social change in circumstances where law cannot–anyhow, laws are state-centric, used and abused and are often tools of aggrandisement of the state power as well as that of its allies. The Bhopal disaster was a rude jolt, and made people aware of the ticking time bombs that the mismanaged chemical industries were.

very nice post . very well written. love to many more post like this