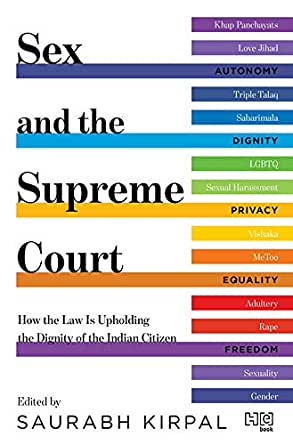

Mr Saurabh Kirpal is a lawyer and an LGBTQ activist based in Delhi and has made a significant contribution to the LGBTQ movement by actively standing up against 377 and challenging the notions against the community that prevails in our society. He was the editor of the distinguished book ‘Sex and the Supreme Court,’ and has been at the forefront of spreading the message of diversity and inclusion in the gender narrative of India. We welcome you sir and thank you very much for agreeing to be a part of this interview.

Kunal: Let us begin with the landmark judgement given by the Supreme Court around two years ago. Since section 377 was amended on September 6, 2018, how do you see things now? Do you believe it has made significant changes in the life of the LGBTQA+ community in India?

Saurabh Kirpal: I believe it has…you see, a single judgement is not sufficient to change the mindset of the society. So it’s not as though this is some kind of a panacea or a magic wand by which, suddenly the lives of every queer person in India suddenly becomes perfect or equal to every other citizen. But its made a very significant dent in the discrimination that has been historically faced by the LGBTQ community, and its made a dent in two separate ways – one is, of course, the legal aspect of it, so your act of love is no longer a criminal offence and therefore, the fear that used to exist of prosecution by the police, forms of harassment by the police, that has disappeared and that has empowered a lot of people to come out and admit to their sexuality, and people have done so…as a consequence of this judgement. People feel braver and emboldened that the sanction of the criminal law is no longer there forcing them to stay within the closet. But I think a more important development that has happened is not merely the legal impact of the judgement on the queer community but I think the powerful statement of the law as enunciated by the Supreme Court with the moral authority of the supreme court, I think has made an impact on the psyche of the nation at large really. To me, the most telling thing when the judgement came on the 6th of September 2018 was the remarkable silence of civil society about it and the quiet tacit acceptance by the entire community as to the decriminalization of 377. People accepted it, it was a norm, it was fine because the Supreme Court had said so – it was alright. So I think that was a beginning of the path for the LGBTQ community to start feeling like equal citizens of the country, and correspondingly, it was a path for society at large to start accepting the LGBTQ community as members of society, not pushing people into the closet, not forcing them to stay in the closet; talking about the issue – that is a very important thing that has happened really also after the judgement, Kunal, is that people…I think this has lit a little spark in the community which is turning into the flames of freedom hopefully. So people are not talking about the issues concerning the LGBT community; people are not highly shy, I remember 10 15 20 years ago, that the only time a conversation about the queer community that used to happen used to be first preceded by sniggers or giggles or awkward silences. It was a complete question of putting even the discussion in the closet. Forget about the people who were in the closet themselves, even the discussion or the issue was kept in the closet. And that’s the judgement, I think the impact that has been made -is that people are talking openly about the issues. There is no guilt about talking about homosexuality, there is no shyness, there is no taboo anymore about talking about the issues at least, and that’s a start.

Kunal: The judgement on Section 377 changed many people’s lives. How did it make a difference in your life as a person? Would you be comfortable to talk about that?

Saurabh: Certainly, well look, personally I want as I said the former power, I gave you two effects that the judgement had – one is the legal aspect and the second is the sociological/constitutional/citizenship aspect. As it regards the former, no, that made little impact on me because I was a person clothed with privilege, and hence did not exactly fear the wrath of criminal law, right? So it was highly unlikely that I was ever going to be prosecuted under section 377 and I was a person who was out to the community, to my friends, my family, I live at my home with my parents and my partner, it’s a nice joint hindu family, well, not hindu as my partner is not hindu so a normal joint family, so that made no practical impact on me as regards illegality is concerned but certainly, yes, you know, the judgement of 2013 in the Kaushal case which set aside the Delhi High Court judgement had made me feel that I could no longer fully rely on the Supreme Court of India, and that had dented my faith in the institution somewhat, and it had made me feel as though my country did not fully appreciate me and I felt therefore, that the judgment of 2018 did redeem the constitutional promise of equality and liberty to me as a person, so my faith in the constitution, my faith in the process of law and my faith in the supreme court of india as the prime guardian or the fundamental rights which have been given to us by the constituent assembly makers, by people like Ambedkar, Nehru, great men and women who gave us those fundamental rights that they had a tryst with destiny in the 1950 and we had our tryst, tryst with freedom in 2018.

Kunal: That’s a very interesting way to put it and so very true. We all are aware that the battle does not stop at just decriminalizing. Comparing India to other countries like Canada, Spain, The Netherlands, United Kingdom etc. where LGBTQA+ people have marriage rights, property rights, anti-discrimination laws and even the government-funded pride events, do you think that we are miles away from all these aspects or do you believe that non-inclusive legal structures of India will change very soon?

Saurabh: Well, the two are not necessarily mutually exclusive. I think the answer to both questions is yes. Are we miles away? yes. Will it change very soon? Not only do I hope so, I feel so. So in terms of ‘are we miles away?’, well clearly we don’t have any anti-discrimination law and forget the fact that we have no any anti-discrimination law against the LGBT community which faces the discrimination, we don’t have a general or a generic anti-discrimination law even for women in our country or for a vast majority of minorities or oppressed people. So I don’t think that’s a terribly great priority for the country, for the politicians etc. But the fact is we don’t have that anti-discrimination law and therefore, we are miles away from having full freedom and equality and similarly with the gay marriage issue, it’s not important to certain activists I know but a large number of the queer community and the people I speak to at least would like to have that option on the table and seek gay marriage. I will wait for questions later. So we are quite away from equality, but you know the historical perspective of other countries, if that is to be looked at, it will show one thing, that change when it happens, is very rapid. Partly because society and societal composition are changing as well. I think the youth of today are not as bigoted as us older people and the people of my generation and above. Yes, they may be in power today, the older people they hold the instruments of power in their hand and therefore they exercise an oversized role on the consciousness and the legality of this country. But I think society is changing so fast and young people who have access to developments and knowledge of developments that are happening outside India through the internet, through social media, through just generally being more aware, and politically more active. I think that will permeate into the consciousness of society and I hope young people will speak to their parents, their uncles, their aunts and will change it and I think as I said before that given the relative absence of any hostile reactions to the 377 judgement, I hope that society will change faster. You know sometimes we think, we rue the fact that what kind of country are we living in and we beat ourselves in the chest, there’s tremendous inequality, and that, of course, there is, but I think we also tend to ignore sometimes the softer part of our country, the issue of tolerance which is there in people. Events have brought out the worst in people and people I thought who were otherwise tolerant people have said remarkably horrible things to me in the last 5-10 years and that shocked me and surprised me but more than that I am shocked and surprised because I expect a certain level of tolerance which has always been there in our country. So the bedrock I think of the country is acceptance, inclusion and tolerance with a few minor aberrations of hatred and I hope as regards the LGBTQ community is concerned it will be tolerance and acceptance which will triumph over hatred and bigotry, and that will happen fast.

Kunal: Okay, given that we were just talking about tolerance and inclusion so, a lot of laws are influenced by societal forces. India might be a progressive country in ancient and medieval eras, but talking about now, we witness incidents of violence against inter-caste and inter-religious marriages; even moral policing sometimes in the name of culture and sometimes in the name of Love Jihad. How do you think a society like ours which is entrenched in Patriarchy, Transphobia, and Homophobia, can go about accepting or influencing the path of inclusivity and equality for the community?

Saurabh: Well you see, I think that requires constant effort on the part of the members of the civil society. Yes, you are right there is homophobia, there is transphobia. We are a conservative society but as I mentioned earlier, we are a conservative society with a very strongly tolerant streak. But of course when people are out to fan the passions of hatred against a particular community and the point when a majority community starts feeling threatened by a minority which is very peculiar but it does happen for A or B reason. Then there is a definite problem, right? So, the question is how do we change that, and that was your question, how do we make sure that there is inclusion, that there is none of this hatred towards the other, as I would like to call it. Well, a simple part of it is spreading awareness and empathy, I think that’s the most important thing. When you see someone as the other it is easy to hate them. When you portray someone as being like yourself, it’s a little less easy to hate them. So I think it’s important to end this segregation that has happened in our country. I think we have ghettos of different religions, different castes, now that is probably again – a stratification that has happened historically by virtue of class and religion of course but I think we need to make an attempt to make a dent into that segregation of societies into these groups and castes, doesn’t mean I want a homogenous society, no. That would be to take away from the beauty or the plurality that which is India. What I mean is something quite different, which is a dialogue between different communities, and we, therefore, need greater visibility of these different communities, of the minorities. The most important thing I’d like to say is the medium of the courts. We need to engage the courts and ask the courts to come to the defence of inter-caste marriage or inter-religion marriage. They have in the past done that Nadia’s case, and in various matters relating to inter-religious/ inter-caste marriages as well as the Khap panchayat case. So I think we need to rely on the courts but not everyone can afford to go to court, Kunal. It’s an expensive proposition, a poor person in a small village far away from the high court will not find it easy but those who can afford to go should go.

Kunal: And it’s also a very long fight, as in the court process is so long and so tedious, one ought to have that will power to stay committed.

Now because we were talking about representation, so we know the social structure of a country can become equal only when there is representation of people from all sections of society and in the sense somewhere, I personally feel that the LGBTQ community lacks far behind compared to the other religious or caste-based minorities that we have in India. What laws or policy do you think should be looked into to increase the representation and safeguard the right and dignity of the community?

Saurabh: Well, I think that’s partially correct I would say, in terms of the fact that representation is needed that is beyond doubt, a fact that we do need a greater representation of the queer community in all sectors of or spheres of power – be it political, be it judicial…its a psyche at large. But you know reservations may not be the answer in the political sphere in the country has been trying to get one-third reservation for women in Parliament and that’s been a non-starter for the longest-longest time. So I think that is probably a more important thing to focus on because you said earlier in your opening comment that the queer community is more disadvantaged than most communities, I don’t think that’s necessarily true. There are intersectionalities and there is… let’s not get into the question of competitive victimhood, so, I think that cause of women, however, nevertheless for reservations, is much greater in terms of the demand of the queer community. You know we are still a much smaller minority, so representation will, even of a small amount will make us roughly equal in the political sphere but 50 per cent of the country is women and you have barely any representation of women in politics and I was seeing some statistics yesterday that out of about some 1200 judges of the higher judiciary, only about 80 are women, right? So given that level of disparity, I think the need for reservations if at all is there for women. However, having said that there is a case I think for reservations in public employment for certain parts of the queer community for certain sections of the LGBTQIA community so not necessarily lesbians and gays necessarily because a lot of us come from privileged backgrounds and we don’t need reservations. So if you see the NALSA judgement, there was a suggestion there. In fact, a direction that there should be reservation in government employment for the trans community. I would say that therefore may be necessary but even within the trans community, I would say there should be a further subset which should get reservations. So trans community as you know is an umbrella term so it has trans women, men, transgender. It’s a large umbrella of sexuality, so let’s not get into the technical details but within that, I would say, maybe the hijras and the kinnars are as a community there has been traditionally been treated very very poorly. Right, so the idea of reservations is somewhat akin to a historical system of reparations. So any community that has faced rampant discrimination historically, we offer reservations as a form of reparations to level the plain field, so it’s not sufficient that someone is disadvantaged today for A or B, C reasons, to ask for reservations and thereby breach the equality clause of our constitution. We need something more which is to show that there has been a such a fundamental inequality from the beginning to that community that they need reservations to rectify and remedy that, right, because reservations have two sides while it’s very easy to say that we give reservations to somebody, it inevitably has an impact on the person who is not getting reservations. So this is something that has to be dealt with delicately and cautiously. So, therefore, I am saying – limit the reservations that are available to the queer community, to the most disadvantaged and the underprivileged of the community and that would be hijras and kinnars who really have no source of income, who are ostracized by society and need all the help that they can get.

Kunal: When we talk about bringing change, it must start at the grassroots levels. As our primary socialization starts from schools, it becomes crucial to include lessons on gender inclusivity and alternative sexualities at this level and make children aware of gender sensitivity and sexual diversity. However, these things are not included in the Education Policy. What do you think can be done to make our school curriculum more inclusive?

Saurabh: You talking of gender sensitisation and inclusion and there’s barely any discussion of sex education in our curriculum. I think this is a taboo subject and I don’t see given the current dispensation that there is any likelihood of inclusion of these ideas of sexual preferences and the gender fluidity in our curriculum. It’s not just going to happen. It may be needed, I think it’s needed but it’s not going to happen so how do we go about remedying that. I think that is an initiative school will have to take on their own. And it’s an initiative that parents will have to take with their children. This will be something that will have to be done at home. It’s highly unlikely that it will be done at an institution or at some institutional level so by institutional level I mean by the NCERT or the school boards. It should however be done by institutions at the school level. Independent individual schools can do it and there are schools who are currently doing this, at least in Delhi I know of a few schools which are doing gender sensitization and talking about sexual preferences and that’s necessary because that also curbs bullying. Because one of the biggest problems the LGBTQ community faces is when a young queer person is bullied in school so that’s important but this has to begin at home really. We need to educate parents to do this.

Kunal: How do you think homophobia exists in our courtrooms and how does it function as a potential hindrance in the path of a person’s personal or professional life?

SK – Well, homophobia does exist in every aspect of our lives and it is no surprise therefore that it exists even in the courtroom, of course, some part of it is internal fear of someone’s coming out but I think there is distinct homophobia maybe not in the high judiciary as much even though I think there is still some but certainly I think the biggest problem a young lawyer has when they are queer is to expect clients to take them seriously. I think more than the judges, I think the greater fear is how will your clients react to you. So yes there is homophobia and I think the only answer to that is come out in numbers and make it. That’s why I came out many many years ago and try to smash that homophobia and that, it will happen that way I think. Just normalize it and there is nothing to twitter and gossip about if you are out. Someone will laugh and say he is gay and that’s the end of that.

Kunal: I was reading a couple of articles which were dealing with same-sex marriage in the US and the marriage equality and they were talking about. Along with taking the legal route, they also took a societal route in which they were making people aware about it, that it is just demanding equal rights of marrying as a straight couple would, as a heterosexual couple would. Even people within the LGBTQ umbrella want the same equality. So it’s nothing but equal rights to marriage. How do you think a similar model can be taken up in India wherein, along with taking the legal route, there is more sensitisation of people and normalization within our social sphere?

Saurabh: I think that’s absolutely imperative. I don’t think there are two questions about the fact that a legal battle alone is not sufficient. And it’s not only a question of the legal battle being sufficient. I don’t think the legal battle can be won without having some change in society because judges who are going to decide this issue eventually are not people who have been snatched from mars, they are members of our society who live in India and are drawn from our milieu, our way of thinking. So they will obviously reflect and respond to consequently what society is thinking and that’s why I think the 2018 judgement was easy to come by because by then society had also changed. So yes we need to make a change in society; we need to enter into a discussion that to have gay marriage doesn’t mean the destruction of religion. One can keep religion because that’s the greatest fear that is often expressed is that it is opening the flood gates to all kinds of things and therefore it’s an assault on religion and you have to maybe comment and say that this beholds religion, this is above or beyond religion, this can be under special marriage act. People are not asking necessarily to go to the temple and insist that the priest marries them if he doesn’t want to marry them. The ability however to go to a court of law which is a secular institution and seek recognition of that partnership and marriage under the special marriage act, that is what is being sought, and therefore if that is discussed about and debated and you know I think people’s hearts and minds will change and that will make the fight for marriage equality better and easier.

Kunal: Why do you think there is a lack of political will in bringing legislation on this subject? The Parliament holds the power of giving the LGBTQ community all their due rights but so far there is no attempt by them to bring anything concrete. Why do you think this is happening?

SK – Well I don’t expect the political class to take it up, let’s be clear about that. Because it’s simply not politically popular to do so. That’s why the political class is not taking it up. You mentioned the fact that we have to have societal sensitization that shows that society is not yet sensitized, right? That’s why we need sensitization, and to say that society is not sensitised means the politicians are not interested in it because they want votes, and they don’t want to do anything which is unpopular so, therefore, that’s why they are not going to do it. I don’t expect and this is not again, I repeat, an Indian phenomenon. It’s a worldwide phenomenon that this is the case where the courts lead and the society follows, right, because they are so out of the mainstream that for society to accept it per se is not, is simply not going to happen. So you need these changes and these changes will come top-down effectively really from court into society rather than the other way round. I am saying there is a symbiotic relationship between our societal functions and court functions and there will be an interplay and dialogue between the two. Nevertheless, the final order will have to come from the Supreme Court or the courts at large and it’s not going to come from politicians. In 2018, the government could have amended the law, could have supported the Supreme Court striking down section 377 and chose not to do so and simply said we leave it to the wisdom of the supreme court to do what they think is right as though the court is going to do anything other than that, but without any sense of irony, this is what they said in court, so even at that point there was no political will to do something even for which there was the consensus. So I don’t expect change to happen. It’s not politically popular, so the change will happen through courts and I have faith in the courts. It will take time as I remember the very old dialogue ‘ tareekh pe tareekh’ in the court, and they say the wheels of justice run slow, but as Martin Luther King also said that, ‘the arch of history bends slowly, but surely towards justice.’

Kunal: Thank you so very much for doing this interview. I am so very grateful.

Disclaimer: This interview has been edited for clarity.

Kunal is a Delhi based lawyer & policy analyst and has been working in the social sector since the last seven years. He is the Founder of ITISARAS and currently presides as the Chairman of the Governing Body of the organisation.