Not just art for art’s sake, literature has been an eminent record of the milieu to which it pertains—social, economic, and political. A kaleidoscopic reflection of society, art gives a voice to the ones who have been oppressed and have lost the legitimacy of their voice; a space wherein they can find an expression of their selves.

This stands true for the LGBTQ+ community as well. It is essential to point out here that the homophobic idea of the LGBTQ+ community as being “unnatural and against the course of nature”, as per Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code is a prerogative of the West, of the Victorian and Judaeo-Christian ascendancy. In our traditions and cultures, the LGBTQ+ community’s existence is considered “merely an impure act”—well, amongst many other things.

A close look at the traditional Hindu texts and mythological epics reveals an overflowing presence of sexually ambiguous characters, and the co-existence of several sexual identities, and the presence of people of the “third gender”. The Mahabharata is filled with stories depicting Arjuna’s numerous escapades, from killing a hundred cousins to marrying several women and siring multiple children. Arjuna was also cursed by a nymph and had to spend a year as a eunuch. The tale of Skhikhandi, the intersex warrior killing the mightiest warrior Bhishma for revenge and many other tales prove that our society can never escape gender fluidity, even when narrow mindsets propagate homophobia and hate.

Same Sex Love in India, edited by Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, traces the entirety of queer literary history writing in India from the Pali Jataka to contemporary narratives and depicts how homosexuality has been represetented as diabolical. R. Raj Rao’s The Boyfriend, considered the first gay novel in India, is full of irreverent, dry humour that examines the realities of caste, class, religion, masculinity, and gay culture in India. The representation of transgenders in Indian literature has been confined to autobiographies like A. Revathi’s A Life in Trans Activism, which gives us a glimpse of a transwoman and her quest of finding her identity through activism. The regulating attitude of the state initially began with colonial rule when Indian historical sources entailing sexual themes were rejected. Since the term censorship has haunted the LGBTQ+ community since time immemorial, online platforms have become significant avenues for the LGBTQ+ community to channel their artistic talents.

Since advocating gay rights and creating LGBTQ+ literature, especially in English, are considered the exclusive rights of upper caste and upper-class men, casteism and patriarchy are often reinforced in these representations. Maya Sharma’s Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Underprivileged India documents the life-stories of ten working-class queer women living in north India and dispels the myth that lesbians in India are all urban, westernised, and come from the upper and middle classes.

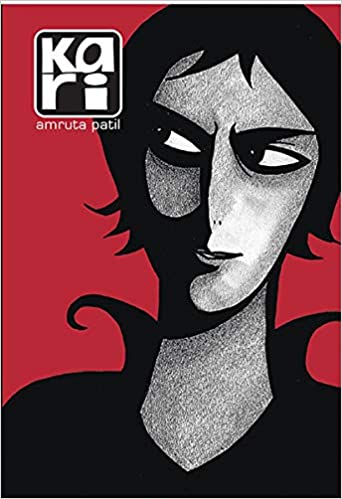

Another genre of literature that has brought about a revolution and rebellion and has helped in finding unheard voices is that of the graphic novel. While the term “novel” itself emanates a grandeur of sorts, the graphic novel is an amalgamation of comics and of storytelling through artwork and words alike. They primarily indulge in topics that are individualistically deep-rooted, historically inclined, and psychologically probing. They help give expression to alternative narratives of history of and socio-political predicaments fazing our milieu.

One such predicament lies in the issues surrounding the LGBTQ+ community, and a prominent work within the graphic novel genre is that of Amruta Patil’s Kari. The story is about a lesbian relationship between Kari and Ruth and how they are separated after an attempted suicide in the beginning of the narrative. Kari’s bildungsroman-like journey of finding her ‘self’ within a heteronormative culture-scape is about friendships and about love. Patil ingeniously weaves her illustrations with the storyline and gives an insight to the suffocation and claustrophobia one might feel in a metropolitan city, a highly heterosexual society at that.

For all the diversity that we boast about, it is imperative to acknowledge the fact that regional works pertaining to the LGBTQ+ community do not get as much appreciation and cognizance as mainstream literature. The media oftentimes sidelines their narratives for the modern-urban-ideal gay man, who apparently singularly represents the community. The hegemony and predominance of English as a language also forces other members of the LGBTQ+ community to be swallowed up either by losing themselves in translation or being limited to the particular language to which they cater. It also leads to the predicament wherein due to fear of being ostracised, the LGBTQ+ community depends on members of the heteronormative reality to give voice to their stories. This indeed does help in bringing about an awareness but the narrative and perspective of the community becomes once removed—their voice gets lost.

One would be surprised to know about the number of works that have been written in various regional languages. To name a few, Pandey Bechan Sharma’s collection of eight Hindi same-sex love stories, Chocolate; the renowned Urdu short story Lihaaf by Ismat Chugtai; Kamala Das’s Malayalam autobiography, Ente Katha; Vijay Tendulkar’s Marathi play, Mitrachi Goshta; Vasudhendra’s Kannada work, Mohanswamy; Bindumadhav Khire’s Marathi compilation of stories of parents of LGBTQ+ people called Manachiye Gunti; and Kishor Kumar’s Malayalam autobiography Randu Purushanmar Chumbikkumbol, amongst many others. Most of these works have been translated into English as well, the language that bridges the various regional spaces together.

A very important aspect that is not generally dealt with, one which has real-time implications in the lives of the LGBTQ+ community, is childhood. Most of the trauma and anguish they experience stems from their childhood, a time they many struggled to stay afloat in the whirlwind of reality wherein concepts of gender identities and sexual orientations do not form a part of their realms of understanding. They were conditioned from an early age to adhere to heteronormative rules and regulations. This, in turn, coerces them to live in a make-believe world of self-deprecation, shame, and a guilty conscience of being “unnatural”.

Literary representations of childhood would help in aiding those children who identify themselves to be part of the LGBTQ+ community on one hand, and on the other, it would help in creating awareness about it, and ultimately normalising it. A few writers have taken it upon themselves to take this approach. Few of these works have been emotionally charged and indeed thought-provoking for all types of audiences, of all ages. To name a few: Talking of Muskaan by Himanjali Sankar, Payal Dhar’s Slightly Burnt, Omid Ravazi’s Let Me Out, amongst others. It is a start for the LGBTQ+ community to find solace and understand their own selves through fiction, which can help them come out of the closet. This is a discussion that can never really be over: there will be a myriad of sub-topics, angles, and additions that can be made and discussed. This was meant to be a start, amongst so many other conversations that have already begun. The more noise we make, the more we will be heard.