By Vinaya. K

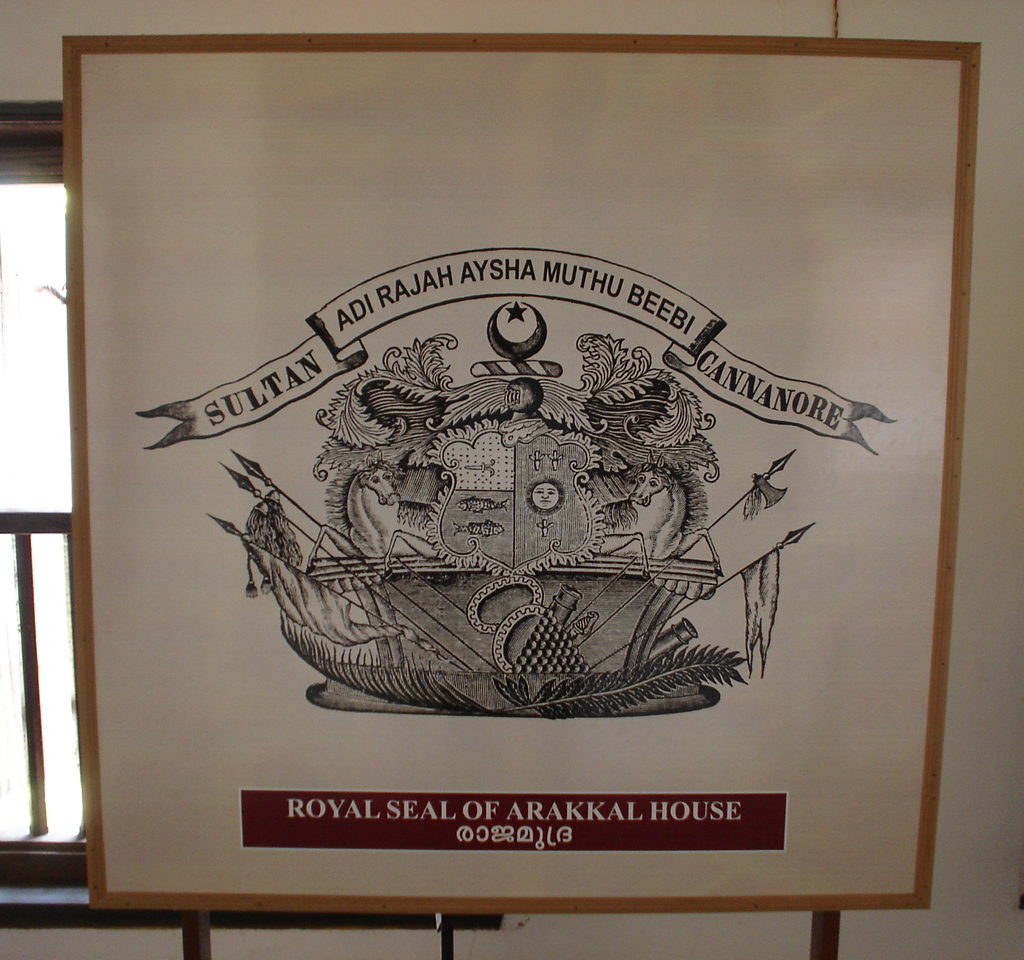

“The most powerful of all the moors, who maybe regarded almost as an independent prince resides at Cannanore. He is entitled as Ali Rajah, king of the islands…” In the beginning of the 18th century, this is how a ruling house of Malabar was described by the Dutch captain Jacob Visscher in his letters. This ruling house, the Arakkal royal family, which ruled what is today known as Kannur and the Lakshadweep islands, is the first and the only Muslim royal house of India’s southern coastal state, Kerala. This Muslim royal line unlike its counterparts of the world strictly followed Hindu matrilineal succession. The firstborn child regardless of its sex ruled the kingdom; if it were to be a boy, he were to be ‘the Ali Rajah’ (Adi Rajah) and if were to be a girl, she were to be the ‘Ali Rajah Beebi’ (Adi Rajah Beebi). This Hindu custom of succession had later been sanctioned by the Caliph as the ‘custom of the land’ in one of his letters. The origins of the house still remain obscure. From keralolpathi, an ancient Malayalam text to the recent historical studies, there are at least four prominent stories related to the origin of the Arakkal royal family but one thing that is clear from these ‘stories’ is the Arakkal family’s relation with another local ruling house Chirakkal and the Kolathiri of Kolathnadu. Earlier, the feudatories of the Kolathiri, the Arakkal house of Cannanore came into prominence by establishing its political power in and around Cannanore by the middle of the 16th century. It enjoyed a monopoly of trade in the area. Through the attainment of political influence and economic prosperity, the house later claimed independence from the kolathiri.

In 1497, when Vasco da Gama set out from Portugal, it was the dawn of a grand-new epoch in human history for, it not only changed the fortunes of the western world but of all the people who came to have contacts with it. The Malabar Coast was one of the many first places to have developed such contact. It has a long and tiring history of connections, cultural friendships, rivalries and ‘colonialism’ for people to talk about than other regions of the subcontinent. “The visitor to India [who] rarely finds his way to Malabar; he misses much”, said Sir Evan Cotton in his forward to prominent historian K.M Panikkar’s book ‘Malabar and the Dutch’. Such was the diversity of cultures, customs, caste, ethnicities, etc., that existed there, combined with “delightful scenery” .The ‘Hindu’ rulers, the ‘Muslim’ rulers and the ‘Christian’ rulers eventually competed with each other to have political supremacy over the land. Even though religious bigotry and economic motivations were the majorly cited forces behind the violence that existed between them, it was never the sole driving force and the political picture. It was never the ‘us vs. them’ scenario. All local rulers united against the Portuguese by the end of the 16th century which eventually led to the decline of the power of the Portuguese in Malabar. Later, the Ottoman rulers wanted to follow matriliny, as it was “the custom of the land”. And now is a perfect time to recall what happened in the past, for this is an age when dominant ideologies reduce history into a mere political tool. ‘Arakkal kettu’, the palace where the glorious Ali Rajas and Ali Raja Beebis resided, still stands even though the royal swords have rusted and the stories of resistance looms only in the myths and songs. It’s clear that the legacy lives, reminding us of the culture and diversity of the land. After all, all history is not something that happened long ago, but it indeed is a “constant conversation between the past and the present”.