By Ritika Soun

The colonial rule has left the Indian soil decades ago; however, we can still feel reminiscence of it in our surroundings. This is reflected through artworks, architecture and is even visible in our cities and towns. Whenever the ground is opened for discussion on ‘culture’ we all have our subjective understandings of it. For some, it is associated with beliefs, religion and morals; for some, it shapes an individual’s personality, while some even go to the extent to affiliate ‘culture’ with food, caste, and ethnolinguistic identity.

India, since time immemorial, has had a mixture of syncretism which it has experienced throughout the ages and, the process of acculturation – which is also a major part of our present ‘unity in diversity’ and an integral part of our everyday lives. When seeing our glorious past we do not find it cryptic, rather we tend to believe it as very simple and linear. However, with a deep analysis – what we get to know is the fact that – it is all an aerial view. It requires more absorption into this topic. One of (the many) factors or elements that we can focus on is the ‘Colonial consumption of the Indian culture.’

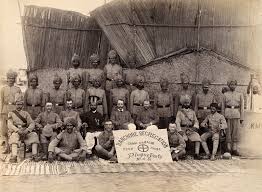

This element caters via artworks, architecture – urban spaces particularly and buildings in its broader sense. The Indian cultural context during the colonial period majorly consisted of ‘segregation’, which did not just mean spatial segregation of population, but also physical, psychological, caste-based, as well as ethnic and religious segregation. It was visible through the design of the cities and towns, as planned by the colonials. However, it cannot be negated that this colonial phenomenon was also experienced by other British colonies. The major distinction was between the ‘rural’ and ‘urban’. The central factors influencing these preconceived notions are – demography, geography and politico-economic conditions, which also affected other minor and associated factors.

According to the British map for the planning of towns and cities, the common feature was the segregation between the ‘black’ and ‘white’ towns. These hierarchies were defined by class and occupation, which in part replicated the colonizer—colonized racial boundaries. These were maintained across space through bodily regulations. For instance, they were deployed in the name of sanitation and public health to contain labouring and sexualized bodies within certain spaces of the city. While on the other hand, the housing or residential areas of highly paid colonial governors were located near or closer to the government centres or administration complexes. This ‘spatial segregation’ can also be witnessed in the present context through different localities that are present – some are posh areas, comprising of the big-shots (mainly) of the society; some are defined by the occupation/ profession, like the governmental bungalows or housing complexes; while some areas project outright poverty, like; slums and local bastis on the peripheries and borderlines, while others, like sub-city areas/ cities, shelter the working- class. This spatial segregation does not end here; it is further extended to the type of urban houses/ complexes. For instance, it could be a single-roomed flat, or a double – roomed flat and sometimes with servant quarters/rooms.

The colonial housing made provisions for their officials or governors, but they did not provide an outlet for domestic help. This forced them (domestic help) to arrange for their shelter nearby – which gradually would have converted to slum or local bastis or unauthorized colonies (as we know it now) over the centuries. This was because colonial cities inscribed social and economic hierarchies upon expanding urban terrain, turning the urban areas into centers of economic domination. This also turned the urban cities into spaces of ‘control’ and ‘autonomy’.

This brings us to another factor – ‘public’ and ‘private’ space. The public spaces are the ones which make the cities in terms of its architecture and administrative functions. On the other hand private spaces have been the core of reflecting the patterns of public into the private households – giving entry to colonial cultures to consume from the private space as well. However, there was fluidity between the two in the past in comparison to the present. This fluidity allowed the colonial domination over the Indian cities and hence could be inferred that it was the British or colonial culture that consumed the native culture. Due to the British occupation of the cities, it brought some changes which were also evident in the ‘urban lifestyles’. Moreover, many cities turned to the arts, cultural and creative sectors to sustain their economies, de-industrializing sites and creating new lifestyle opportunities for residents. This came with the issue of ‘high culture’ and ‘low culture’. In our case, high culture equates to the colonial and, the low culture with the native Indians.

In contrast, the rural households remained self-sufficient for much longer, and the mode of consumption in rural areas shifted slowly and only as a result of their increasing involvement in commercialized agriculture, which allowed households to earn money to spend on textile yarn or ready-made cloth. E.g. The Indian handicraft industries and textile industries were shut-down, affecting the Indian market worldwide.

Additionally, the consumption of Indian culture can also be viewed through the ways the colonizers conducted themselves in public spaces. For instance, the ‘Dilli Darbar of 1911’ was to commemorate the coronation of George V and Mary of Teck in Great Britain and announce their proclamation as Emperor and Empress of India. It was an Indian imperial style mass assembly organized by the British, similar to the Mughal Darbars that were held in the past. This was also an attempt to acquire social and political legitimacy from the Indian masses.

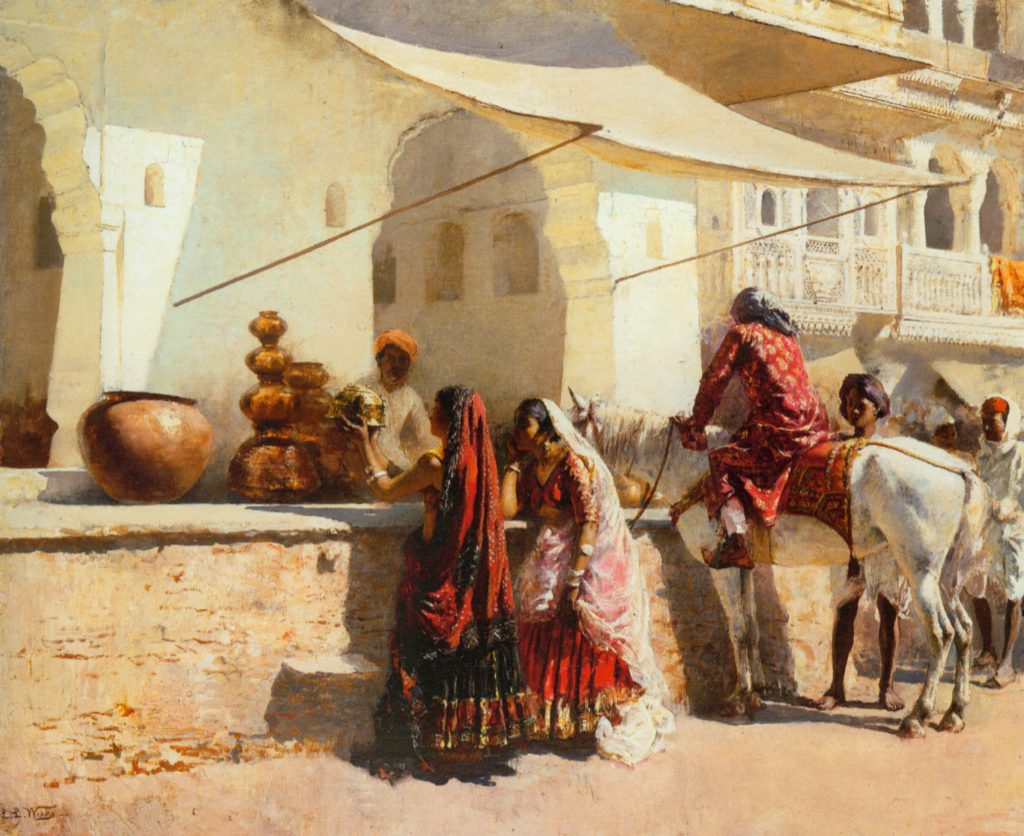

Moreover, European consumerism (at the cultural level) also laid emphasis upon the non- European aspect where the colonizers would routinely exhibit the colony – in our case in point, India, under a special category of ‘exotic’. This was to exhibit India (along with the physical reliefs) to the people of London. These printed images stereotyped the Orient as an enchanted, exuberant, ambiguously Mughal locale of luxury and royalty. However, this whole thesis of consumption could also be viewed through the lens of ‘nostalgia’, which could be seen through their exhibitions of Indian colonies in Britain.

Hence, the consumption of culture could be understood as a two-way road rather than as domination of any one culture.