‘Death’ has always been conceived as a significant aspect of the built heritages of the past. A quick glance at the surrounding landscape of Delhi would often prove such a thesis as evident from the Humayun’s Tomb, Lodhi tombs, and the Nizamuddin Dargah that lies here, which situate itself to popular imaginations of the people and that of a glorious past. Bereft of such embellishments and the glory that ignites nationalism, the Nicholson Cemetery presents a sharp contrast to such reminisces and often reminds of the dark history of the city of Delhi.

‘Death’ has always been conceived as a significant aspect of the built heritages of the past. A quick glance at the surrounding landscape of Delhi would often prove such a thesis as evident from the Humayun’s Tomb, Lodhi tombs, and the Nizamuddin Dargah that lies here, which situate itself to popular imaginations of the people and that of a glorious past. Bereft of such embellishments and the glory that ignites nationalism, the Nicholson Cemetery presents a sharp contrast to such reminisces and often reminds of the dark history of the city of Delhi.

Nestled in the niche locality of Delhi, juxtaposing the Kashmiri Gate, lies the Nicholson Cemetery. The cemetery was born out of the influx of the Christian community who began to inhabit the fortress of the Red Fort just after the fall of Delhi in the year 1857. Although initially named the Old Delhi Military Cemetery, the graveyard was rechristened later under the name of its famous inhabitant, John Nicholson.

Dotted with the graves of the new and the old, a close inspection of some reveals them to be of those who died during the siege of Delhi. Graves of Rifleman Walter Wooley or Captain Stanley Slater are evidence of such an instance that also gives out their close connection with their peers, superiors, and comrades as marked by the inscriptions and being built in loving memory of their mournful death. However, a significant portion of this silent space is dominated by the graves of children, who may have died a premature death with a parting word of their parents on their grave stele indicating the transience of life at that time. Profuse with other such graves, the cemetery, however, is made eminent as it inhibits the grave of the celebrated ‘Hero of Delhi’, John Nicholson.

Dotted with the graves of the new and the old, a close inspection of some reveals them to be of those who died during the siege of Delhi. Graves of Rifleman Walter Wooley or Captain Stanley Slater are evidence of such an instance that also gives out their close connection with their peers, superiors, and comrades as marked by the inscriptions and being built in loving memory of their mournful death. However, a significant portion of this silent space is dominated by the graves of children, who may have died a premature death with a parting word of their parents on their grave stele indicating the transience of life at that time. Profuse with other such graves, the cemetery, however, is made eminent as it inhibits the grave of the celebrated ‘Hero of Delhi’, John Nicholson.

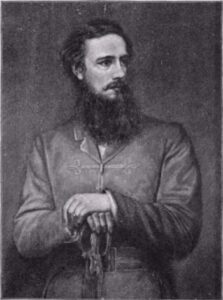

Being born an Irishman on 11 December 1821, it was in India that he spent most of his life, beginning first as a soldier in 1839. However, the fame and glory for which Nicholson is remembered were not presented to him till an open revolt in the form of an uprising in 1857 against the East India Company took place. The Company reached a sensitive position when important centres of British administration were taken by the mutineers with formerly allied kingdoms in open rebellion. After the capture of Delhi at the hands of the rebel forces, the city’s fort was transformed into a nexus for the uprising.

To maintain the company’s sovereignty and annihilate any rebellion, an allied division, composed mostly of European and Sikh soldiers was commandeered by the newly elevated Brigadier General, John Nicholson, who strategically stationed the army at the Delhi ridge. With repeated attempts to barge into the fort, a final assault on 14 September 1857, led to an avenue to attack from the northern gate of the walled city. Soon enough the British stormed, carrying out a general massacre through bullets on the unarmed citizens of Delhi. However, John Nicholson, the main tactician behind this attack, died in a skirmish by the rifle of a rebel sepoy before the British took the city completely. Bringing victory in the face of huge odds, he was thus immortalised as a ‘Hero of Delhi’, being elevated as a representation of the indomitable spirit of colonial determination.

Nicholson’s death and his achievement were thus buried, being topped over with a white marble tombstone inside a city that he won for the British but couldn’t see long enough as a victory of his design. Even after the death of British Imperialism, the grave still lives on at the cemetery, situated along the left-hand side of the central path to its entrance. However, the once glittering white marble slab is now smudged with black spots, with him resting below it but only in a harrowing peace.

Dilapidated in condition and neglected in attention, his grave has shown some evident evidence of cracks with many of its imposed letterings being removed from places making it illegible to even read the text completely. Even with its physical deterioration, the memory of the man who lay buried here has waned with no intention to retrospect it due to its history of bloodshed and defeat, being contrary to the growing nationalism in the current political affairs. The state of its condition is not just limited to the sole grave of Nicholson alone but extends to other graves who died with no inheritors to conserve it and lay buried within a thick cultivation of wild vegetation.

Call for its restoration has already been put forth with the initiation of its detailed documentation under the headways of INTACH’s Delhi Chapter in 2018-19 with a thrust provided by the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA). However, even with an intensive categorisation of each grave at the cemetery and a description of its present state of conservation, no support has since been provided by either the NGOs or the Delhi Government in preserving it. Inadequate attention and an influx of outsiders inside the boundary of the cemetery have also contributed to the deterioration and vandalism of this dispersed heritage with a responsibility to be shared by both the managing trust and the nearby citizens.

Call for its restoration has already been put forth with the initiation of its detailed documentation under the headways of INTACH’s Delhi Chapter in 2018-19 with a thrust provided by the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA). However, even with an intensive categorisation of each grave at the cemetery and a description of its present state of conservation, no support has since been provided by either the NGOs or the Delhi Government in preserving it. Inadequate attention and an influx of outsiders inside the boundary of the cemetery have also contributed to the deterioration and vandalism of this dispersed heritage with a responsibility to be shared by both the managing trust and the nearby citizens.

With the development of tourism in the country, a general interest has been fostered in exploring the built heritages which exhibit the myriad history of a region or state. It thus becomes crucial to preserve these heritage sites that have a close association with the intersecting histories of conflict, turmoil, and politics. The cemetery of Nicholson thus explores such dimensions of significant yet disdainful events that sustain a dimming essence of Delhi. Attention to its physical state and the significance of such a cemetery in the process of history-making to the public and the concerned agencies becomes important to preserve the imprinted history in the memories of the living or the steles of the departed.