Alexander the Great’s campaign in India was ill-fated, but it transformed the material culture of India by introducing Hellenism. Between the conquests of Alexander in the 4th century BCE and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE, Greco-Buddhist art flourished. It was the visual representation of the cultural syncretism between Classical Greek culture and Buddhism which thrived under the Indo-Greeks and the Kushans in Gandhara, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Buddhist art of the Gupta Empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia.

Located in the Northwestern part of ancient India, along the Silk Route, the ancient region of Gandhara had always been a site of cultural interaction due to invasions, immigration, emigration, diplomatic links, and trade communications. This is attributed to the cosmopolitan nature of Gandhara art. The artists in Bactria also worked in Gandhara and intermingling was the only constant. The relief sculpture of Buddha and Vajrapani from the 2nd century illustrates that the artist was probably a Greek, who was unaware of Buddhist values and beliefs, and who sculpted the frieze in the service of foreign devotees.

Located in the Northwestern part of ancient India, along the Silk Route, the ancient region of Gandhara had always been a site of cultural interaction due to invasions, immigration, emigration, diplomatic links, and trade communications. This is attributed to the cosmopolitan nature of Gandhara art. The artists in Bactria also worked in Gandhara and intermingling was the only constant. The relief sculpture of Buddha and Vajrapani from the 2nd century illustrates that the artist was probably a Greek, who was unaware of Buddhist values and beliefs, and who sculpted the frieze in the service of foreign devotees.

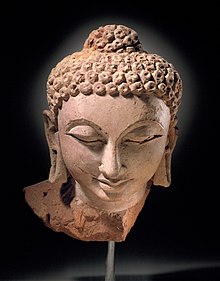

Light toga-like himation (Buddhist characters wore dhoti loincloth before), the contrapposto stance of the upright figures, the stylised Mediterranean curly hair and top-knot, hovering winged figures holding a wreath, floral scrolls and vines, particularly acanthus leaves, were representative of Hellenistic flair. Gandharan scenes of cupids holding rich garlands, sometimes adorned with fruits, had an extensive influence, as far as Amaravati on the eastern coast. Another definite borrowing was the linear Greco-Roman concept of time, and the use of space between the figures and divider motifs within compositions to break the flow of continuous narrations. Illustrations of Hercules are also found, in the friezes, relief sculptures and pillars of stupas, temples and monasteries.

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha probably started after Alexander’s campaign. The Hellenistic ideal human form, mimicking a Greek athlete, was adopted to embody the Buddha. The Hellenistic concept of characteristic features, such as elongated ear lobes and the ushnisha on top of his head, were used to identify him. A strong sense of artistic realism can be witnessed with some of the standing Buddhas even having hands and feet of marble to increase the realistic effect and the rest of the body in another material. The importance of certain characters was communicated through size.

Bodhisattvas are depicted as bare-chested and jewelled Indian princes. Buddha was modelled after Apollo, the Greek god of the sun. However, the earliest Hellenistic statues of the Buddha portray him in a style reminiscent of a king, probably the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius I (205-171 BCE), also known as the “Saviour King”. They were portrayed with the same protector deity, the Greek god Herakles.

As Buddhist art developed from a spiritual focus to an embodiment of culture, it embraced different cultures while adapting them according to its own philosophy. The buildings in which they were depicted also incorporated Greek style, with ubiquitous Indo-Corinthian capitals and Greek decorative scrolls. Over the years, these Hellenistic traditions were carried over and some were incorporated by the Muslims as well. A common example is the Acanthus leaves, a Mediterranean plant that made its way into India through Buddhist artistic depictions and can be found in the sarcophagus of Safdarjung Tomb. This was not just a one-way process as scenes from the life of the Buddha are depicted in a Greek architectural environment as well, with the protagonist wearing Greek clothes.

As Buddhist art developed from a spiritual focus to an embodiment of culture, it embraced different cultures while adapting them according to its own philosophy. The buildings in which they were depicted also incorporated Greek style, with ubiquitous Indo-Corinthian capitals and Greek decorative scrolls. Over the years, these Hellenistic traditions were carried over and some were incorporated by the Muslims as well. A common example is the Acanthus leaves, a Mediterranean plant that made its way into India through Buddhist artistic depictions and can be found in the sarcophagus of Safdarjung Tomb. This was not just a one-way process as scenes from the life of the Buddha are depicted in a Greek architectural environment as well, with the protagonist wearing Greek clothes.