During the 19th century, as colonies expanded, there was a rising demand for inexpensive labour in Caribbean plantations, particularly in Suriname, Fiji, Guyana, and Trinidad, focusing on crops like sugarcane, coffee, cocoa, and jute. In response to this demand, labourers were initially brought in as slaves and later as indentured labourers, with a significant number originating from India and offered at affordable rates. This migration was closely regulated by ordinances such as the Immigration Ordinance of British Guiana in 1893 and Trinidad in 1899, establishing a comprehensive system to govern every aspect of the immigrants’ lives, leading to the systematic subjugation of the indentured population.

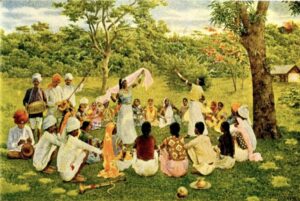

The aftermath of the 1857 revolution intensified distress in the region, depleting resources and subjecting the population to hunger, repeated droughts, and famines. These hardships resulted in widespread unemployment, acute poverty, and destitution. In the face of these challenges, men were compelled to leave their homes and seek employment opportunities in distant lands. The interconnected factors of colonial economic needs, migration policies, and socio-economic distress underscore the complex dynamics surrounding indentured labour and migration during this period. The migration, whether coerced or voluntary, resulted in the disintegration of families, giving rise to emotional, social, and cultural challenges both in their homelands and the destinations they reached. As migrants embarked on their journeys, they carried with them a rich cultural heritage, encompassing both intangible and tangible artefacts such as folk songs, folk tales, and oral memories from their native places

The concept of migration memory extends beyond the tangible, traversing the world through the words, minds, and knowledge of people. Simultaneously, it lingers in the memories, songs, and plays of those who witnessed the departure of others. These migrants preserved and propagated various aspects of Indian and folk cultural traditions while engaging in a dynamic process of cultural fusion with the traditions of their destination, ultimately giving rise to a new cultural amalgamation. A noteworthy illustration of this cultural assimilation is evident in the form of ‘Chutney’ music. Music, as a fundamental component of culture, has played a vital role in shaping societal and personal identities. This genre emerges as a result of the amalgamation of Bhojpuri and Indian folk music with Caribbean calypso and Soca music. The fusion involves the incorporation of Dhantal and Dholak from the Indian subcontinent, Soca beats, and Tasha drums from the Caribbean islands. Characterised by its fast-paced style, Chutney music bears a resemblance to calypso music and has garnered popularity in Trinidad and Tobago. It represents a harmonious blend of traditional Indian and African instruments interwoven with contemporary electronic elements. Often acknowledged as the Indo-Caribbean genre of music, Chutney draws significant influence from Bhojpuri folk music, showcasing the intricate interplay between diverse cultural elements. Traditionally, the term “chutney” referred to lively, fast, and often risqué songs in Bhojpuri, a dialect of Hindi.  Chutney songs were typically characterised by playful rhythms, including four-quarter and three-quarter beats such as kaharva and dadra tala-s. Originally, chutney did not explicitly denote dance music. In fact, the chutney style fell within the realm of listening music, serving as a diversion or interlude to the solemn ambiance of ‘classical’ styles like dhurpad, thumri, or qawwalis. Consequently, the content of chutney songs was meant to be relatively light, in contrast to the weightiness of the aforementioned genres. Under the influence of Trinidadian music, Chutney represented a blended musical style. Originating from preserved traditions in Bhojpuri-speaking regions of UP and Bihar, Chutney music started in Hindu weddings, initially performed in gender-segregated, private spaces by women utilising sexualized steps, expressions, and music. It revitalised folk songs, incorporating various genres like wedding songs, devotional bhajans, narrative birha, and others, forming the core of neotraditional ‘tan-singing’ or ‘local classical music’. The evolution of Chutney music, initially an oral tradition, took a significant turn in the 1950s when Ramdew Chaitoe and Draupadi produced records, introducing energetic tunes with a distinct dance tempo.

Chutney songs were typically characterised by playful rhythms, including four-quarter and three-quarter beats such as kaharva and dadra tala-s. Originally, chutney did not explicitly denote dance music. In fact, the chutney style fell within the realm of listening music, serving as a diversion or interlude to the solemn ambiance of ‘classical’ styles like dhurpad, thumri, or qawwalis. Consequently, the content of chutney songs was meant to be relatively light, in contrast to the weightiness of the aforementioned genres. Under the influence of Trinidadian music, Chutney represented a blended musical style. Originating from preserved traditions in Bhojpuri-speaking regions of UP and Bihar, Chutney music started in Hindu weddings, initially performed in gender-segregated, private spaces by women utilising sexualized steps, expressions, and music. It revitalised folk songs, incorporating various genres like wedding songs, devotional bhajans, narrative birha, and others, forming the core of neotraditional ‘tan-singing’ or ‘local classical music’. The evolution of Chutney music, initially an oral tradition, took a significant turn in the 1950s when Ramdew Chaitoe and Draupadi produced records, introducing energetic tunes with a distinct dance tempo.

The term “Chutney music” was coined in the late 1960s by radio producers, Sham and Moran Mohammad, marking a crucial moment in the genre’s development. Sundar Popo’s arrival in 1969 brought a transformative flavour to Chutney music, infusing it with unique lyrics, guitar, and electronic sounds. The 1970s saw Rohit Jagessar contributing new ideas, expanding Chutney’s reach globally through effective production and distribution. Babla and Kanchan’s popularity in the 1980s, particularly in India, further solidified Chutney’s global presence. An intriguing characteristic of modern Chutney music is the incorporation of sexual and double-meaning lyrics, marking a distinctive aspect of its evolution.

In Suriname and Guyana, precursors of modern Chutney were rooted in folk song traditions associated with lower castes, including dhobi-ganiya and chamar ganiya, and the related gariyal. Chutney, often seen as a new name for khemta, features simple lyrics and stereotyped music styles. Key elements include danceability, adherence to familiar conventions, and meeting basic criteria, with a fast, rhythmic structure in the standard quadratic North Indian folk metre (kaherva). Accompanied by skilled dholak players and the dantal, the focus is on lively singing and clear, strong vocal delivery, with limited vocal improvisation and sparing use of ornaments. Chutney places a strong emphasis on dance, a vital aspect inherited from its folk origins. Initially performed by lower-class women in weddings and chatthi settings, chutney-style dancing later expanded to informal gatherings, such as rumshops in Guyana. Men also engaged in chutney-style dancing during wedding celebrations, often with each other or with male transvestite dancers. The dance involves a limited yet expressive set of standard movements, combining graceful hand and arm gestures with sensuous pelvic rotation, similar to ‘wining’ in Trinidadian culture.

Chutney, as a dance and music genre, is not inherently new in style or content; its novelty lies in the evolving social practice of women and men dancing in public. However, in traditional Indian and Indo-Caribbean societies, patriarchal norms restricted women’s expressions of sensuality, but evolving social dynamics and a growing distance from ancestral traditions have allowed Indo-Caribbean women more social freedom. While ideals of family honor and modesty persist, particularly among Indo-Trinidadians, changing attitudes, especially in the context of Trinidad’s Carnival culture, have challenged traditional norms. The controversy surrounding female chutney dancing reflects a broader social transformation, viewed by some as a legitimate and healthy expression and by others as a form of social protest against male control of women. In summary, the surge in popularity of chutney represents a compelling example of dynamic art forms emerging from the grassroots, particularly the proletariat, before eventually gaining acceptance within the broader social mainstream. As chutney, with its vibrant dance and music, transcends its humble origins and becomes more prominent in public spaces, it mirrors the historical trajectory of art forms finding resonance outside conventional spheres. The chutney phenomenon not only underscores the transformative power of cultural expression from marginalized communities but also highlights the ongoing interplay between grassroots creativity and mainstream cultural acceptance.