During the Mughal era, the conceptualization of the household was fundamentally intertwined with the ideas of family and the institution of marriage. Describing the medieval family structure from this period proves intricate, marked by a notable propensity for indistinctness and an absence of clearly delineated characteristics. The term “Ahl-a-ayal” was employed as a synonym for the English term “family”, connoting relatives and dependents, thereby aligning with the notion of an extended familial arrangement. The conception of an extended family, however, predisposed the occurrence of conflicts among its members. Such conflicts occasionally manifested in overt expressions, notably exemplified by instances of succession wars, a recurrent phenomenon among Mughal emperors with the noteworthy exceptions of Babur and Akbar. The prevalence of polygamy emerged as a dominant practice within the ruling elites, owing to the absence of legislative or religious prescriptions mandating monogamy. This practice, in turn, contributed to the cultivation of expansive familial structures, emblematic of the Mughal social milieu during this epoch. The features of the imperial household went through changes under various Mughal emperors. These alterations were evident in shifts in the concept of family, matrimonial arrangements, the role of women, and cultural practices. The shifting dynamics of terminology and the concept of family during the Mughal era reflected changes in domestic life. In the Baburnama, ‘ahl-u-ayal’ emerged as the term closest to ‘family’, encompassing a wide range of individuals, from Babur’s immediate family to protégés, including children and slaves. Babur employed terms like ‘Abl-u-ayal’, ‘oruk’ and ‘khishan-u-azizan’ each carrying distinct connotations and referencing different family members. ‘Abl-u-ayal’ and ‘Khanivadeh’ suggested a strong phylogenetic link, referring to prestigious families across multiple generations. During Humayun’s reign, ‘Ahl-u-ayal’ narrowed its association to his immediate family, emphasising the family notion around Hamidah Banu Begum, Humayun’s pregnant wife.

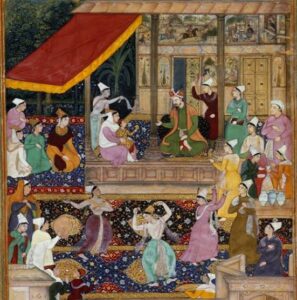

The domestic landscape during the early rule of Mughal emperors, exemplified by Babur and Humayun, lacked a clear demarcation from the public sphere. This changed notably under Akbar, who, in his pursuit to govern the expansive Mughal empire, implemented structural reforms across various domains, including the imperial household. The institutionalisation of the Haram by Akbar resulted in a distinct separation between the private domestic space and the imperial court, as documented in Abu-l-Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari. The term “Haram” became predominantly associated with the women of the imperial household, denoting both the individuals and the secluded physical space where they resided for purposes of consecration. Referred to as “Shabistan-i-Iqbal ” by Abul Fazl, this area was characterised by its inaccessibility to ordinary people and its sacred nature. This reconfiguration of the Haram marked a departure from its meaning during the reign of Humayun. The transformative shift was propelled by Akbar’s strategic efforts to legitimise his claim to the Mughal throne by establishing a connection with the sacred household (Ahl-i-bait) of Prophet Muhammad. Over time, the term, Ahl-i-bayt, expanded to include the “noble” successors of the prophet, positioning Akbar as the “divine monarch” of his era. While the emperor held a de-facto leadership role in the royal household, decision-making in imperial matters was predominantly influenced by age rather than gender. This hierarchical structure negated the concept of a familial head. The institutionalised form of the Haram persisted through the successive reigns of Mughal emperors, witnessing notable changes in the position of women within the imperial household.

Women’s position within the Mughal imperial household is a complicated issue. While Babur and Humayun maintained a modest count of wives and concubines, the era of Akbar saw a notable surge in the number of women. Aligned with the Timurid-Chingiz tradition, women accompanied their husbands to the battleground, and early Mughal emperors permitted their involvement in politics, though without complete sovereignty. Prominent women like Mahim Begam, Khanzada Begam, Maham Anga, and Nurjahan Begum played active roles as mediators and participants in court politics during the reigns of Babur, Humayun, Akbar, and Jahangir, respectively. However, the advent of Aurangzeb’s rule marked a decline in women’s political roles, restricting the active participation of his wives and daughters. The custom of paying homage to one’s mother, known as Buzurg dasht, adopted by the Mughals, is highlighted by Abul Fazl. Despite the initial custom of expressing utmost respect for female relatives, particularly mothers, this practice weakened over time, exemplified by Jahangir’s poignant bowing to his mother. Motherhood became a crucial attribute for women to attain senior status, granting them special privileges, such as the adoption of children, as seen in Maham Anga’s adoption of Dildar Begam’s two children.

Marriage ceremonies played a pivotal role in shaping the structure of the Mughal family, not only establishing a hierarchy among women but also serving as a means to forge political alliances. In the early Mughal history, marriage lacked a defined pattern, a trend that became more structured over time. Babur’s terminology, such as “taking away”, “giving away” and “marriage” reflected considerable flexibility and hierarchy. Under Akbar, these terms were supplemented with additional words akin to the Rajput’s use of “present” or “gift”. Akbar advocated for monogamous alliances with a minimum age of 14 and 16 for girls and boys, respectively. Akbarnama highlighted the introduction of processions (barat) and music in marriage ceremonies during Akbar’s reign, distinguishing them from the earlier Mughal traditions.

Within the top echelons of the Haram, conflicts and differences among women were not uncommon. Titles like ‘Begum’ symbolised royal ladies and princesses of royal blood, while ‘Aghacha’ or ‘Agha’ denoted a slightly lower status, irrespective of whether it applied to a lawful queen wedded to the emperor. Various terminologies like Khawatinlar, Ghum Chachi, and Sarari were employed by Babur to refer to wives, mistresses, and concubines. Over time, concubines began to be referred to as Parastars. Royal children, including Akbar’s daughter and younger sons Murad and Danial, were often offspring of concubines and mistresses. Despite belonging to a lower rank than wives, concubines were frequently married to the kings, yet details about their wedding customs remain unclear. The lack of nuanced information about matrimonial ceremonies, motherhood status, and individual relationships between the emperor and women played a pivotal role in determining the hierarchy of women in the imperial household.

Cultural assimilation played a crucial role in these changes, particularly in the socio-cultural attributes of the imperial household. Professor Harbans Mukhia emphasised the role of cultural seepage as a catalyst for significant transformations in the imperial household, particularly impacting the status of women. The concept of chastity gained prominence during Akbar’s rule, closely associated with the female body and understood in terms of sexuality. This perception reached a point where any glimpse or idea involving the female body was considered a contamination of her self-purity. The portrayal of Gul Safa’s body, a concubine during Dara Sikho, underscored the hierarchy embedded in the notions of chastity and honour within the imperial household. Attributes reserved for the highest-ranking ladies were deemed essential, emphasising the significance of purity and honour. In contrast, Babur’s memoirs rarely applied the term ‘chaste’ to women, and the absence of references to conceptualizations of women’s chastity in pre-Akbar texts, coupled with multiple mentions of festive celebrations in open gardens, highlighted a shift in cultural perceptions over time.

Stephen Blake characterises the Mughal state as a patrimonial bureaucratic empire, where patrimonial dominance emanates from the patriarch’s control over his family. This control involves allegiance to an individual rather than an office and is rooted in mutual loyalty between subjects and ruler. However, the notable presence of matriarchs like Hamideh Banu Begam and Gulbadan Begam during the early Mughal Empire highlights the restricted sovereignty these women were able to afford with autonomy in the decision-making processes of the imperial household.

Stephen Blake characterises the Mughal state as a patrimonial bureaucratic empire, where patrimonial dominance emanates from the patriarch’s control over his family. This control involves allegiance to an individual rather than an office and is rooted in mutual loyalty between subjects and ruler. However, the notable presence of matriarchs like Hamideh Banu Begam and Gulbadan Begam during the early Mughal Empire highlights the restricted sovereignty these women were able to afford with autonomy in the decision-making processes of the imperial household.

The initial Mughal period, marked by Babur and Humayun’s extensive travels, blurred the physical boundaries between the private and political spheres, specifically between the Harem and the Court. The prevailing perception of the Mughal household as a Harem filled with numerous women, primarily for the emperor’s pleasure, perpetuated a narrative that focused solely on younger women. This perspective obscured the diverse roles of women beyond this confined space. It is arguable that the strict delineation of certain spaces as private, feminine, and domestic emerged later during Akbar’s reign. Akbar’s transformation of the Harem into a fortress-like structure may be linked to the evolving character of the Mughal Empire.