India wasn’t untouched by the socialist and communist ideas popularised after the 1917 Russian Revolution. These ideas influenced emerging revolutionaries and organisations, notably the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), founded in 1923 by Sachindra Nath Sanyal as the ‘Hindustan Republican Army’. The organisation’s core principle was achieving freedom through organised armed revolution, envisioning a free India with Universal Adult Franchise and no exploitation. However, even as these revolutionaries advocated for equality, they were influenced by their era’s gender norms. Indian scholar, Ania Loomba, notes that women found it challenging to join revolutionary groups compared to non-violent organisations like Congress ( Loomba, 2019). This article aims to demonstrate that despite their ideals of establishing an egalitarian society, these revolutionaries were not entirely open to women’s participation, as some believed politics was not a women’s domain. Through the examples of notable revolutionaries of HSRA- Durga Devi Vohra and Prakashvati Kapoor, it attempts to highlight the interwoven web of complexities involved in masculinity and femininity in the revolutionary organisations, particularly that of HSRA.

India wasn’t untouched by the socialist and communist ideas popularised after the 1917 Russian Revolution. These ideas influenced emerging revolutionaries and organisations, notably the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), founded in 1923 by Sachindra Nath Sanyal as the ‘Hindustan Republican Army’. The organisation’s core principle was achieving freedom through organised armed revolution, envisioning a free India with Universal Adult Franchise and no exploitation. However, even as these revolutionaries advocated for equality, they were influenced by their era’s gender norms. Indian scholar, Ania Loomba, notes that women found it challenging to join revolutionary groups compared to non-violent organisations like Congress ( Loomba, 2019). This article aims to demonstrate that despite their ideals of establishing an egalitarian society, these revolutionaries were not entirely open to women’s participation, as some believed politics was not a women’s domain. Through the examples of notable revolutionaries of HSRA- Durga Devi Vohra and Prakashvati Kapoor, it attempts to highlight the interwoven web of complexities involved in masculinity and femininity in the revolutionary organisations, particularly that of HSRA.

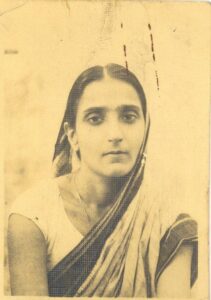

It is due to patriarchy that our society has overlooked the contributions of Durgawati Devi to HSRA and the freedom movement. She is primarily mentioned only for her role in facilitating Bhagat Singh’s escape after Sanders assassination. As a supportive wife, she hailed her husband’s political activities, including lending his personal property for bomb-making by the party. After the discovery of the bomb factory at Kashmir House under Bhagwati Charan’s name, Durga Devi pursued legal means to protect their family home from confiscation due to his political involvement. During this time, she facilitated communication between arrested revolutionaries and party leaders regarding escape plans. Additionally, she procured weapons for the party and participated in a raid to free Bhagat Singh from Lahore Central Jail, After the death of her husband in 1930, she did not even shed a tear so as to keep the secrecy of their hideout intact as informed to us by Kumari Lajjawati. Durga Devi, in her interview with Shyamlal Manchanda, herself recollects fleeing the area and sending her son to someone in Allahabad. Before leaving Lahore, she initially stayed with Kewal Kishan Engineer and later with Rana Jang Bahadur Singh, a journalist for The Tribune, for three weeks. After departing from Lahore, she wore a burqa as a disguise and stayed with Sridevi Musaddi. Her subsequent whereabouts remain unclear, but she constantly moved to avoid police detection. In July, she led a procession commemorating the bombing, known as the ‘Lahore Conspiracy Case’ by Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt (Maclean, 2015). This highlights the patriarchal influence on history writing, which typically focuses on men’s involvement in evading the police and ensuring their safety, ignoring the female role to a great extent.

Moving ahead, one of the most significant activities undertaken by Durga Devi was the Lamington Outrage. On October 28, 1930, Durga Devi and two men associated with HSRA shot a British couple outside a Lamington Road police station. Contemporary newspapers labelled this incident “unique”. Durga Devi recalls having shot multiple bullets. Two things deserve our attention here: firstly, Durga Devi, a widow, accompanied young men in what we can call a “daring act” considering the perceptions of that time. Secondly, she was identified much later by the police. On being informed by a driver that one of the shooters was a Gujarati woman, police thought that the lady was with her husband and started searching for a couple, signalling that a woman on a revolutionary mission without her husband was simply unimaginable.

A study of the life of Durga Devi illustrates that she was actively involved in HSRA works. It appears that initial reservations about women working in revolutionary organisations faded with time. However, one must emphasise here that only women free from familial restrictions could strive to work for the organisation. This bias does not owe its origin to HSRA’s internal policy, rather familial ties rendered difficulties in bringing women into the organisation.

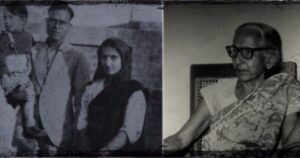

The controversy over the relationship between Prakashwati and Yashpal is one of the most glittering manifestations of gender insensitivities prevalent during the period under consideration. Inspired by revolutionary ideals, Prakashwati supported HSRA by sending her family’s money and even stealing funds and materials for the party. In her autobiography, ‘Lahore Se Lucknow Tak’, Prakashvati informs that as HSRA was facing the need to recruit women into the party to be used as ‘cover’ for revolutionary activities, she was also offered to join the organisation (Pal, 1994). She accepted, agreeing to leave her home. However, she had to leave abruptly when her secret plans were exposed to her family. Prakashwati was an unmarried, young and good-looking lady unlike Durga Devi who was older and being the wife of a respected party member, was held in esteem. These aspects rendered problems for her security and the party’s integrity. Here, Yashpal stresses the need for women to be ‘protected’ by men. Additionally, it also manifests the existence of the idea of young, beautiful women being a threat to the sexual tendencies of men, meaning that they could be attracted towards her and deviate them from the larger party goals.

Upon her initial recruitment, Prakashvati was placed in a house in Qila Gujjar Singh with fellow party members to learn the organisation’s code of conduct. She felt uneasy there, citing offensive language from two comrades and persistent attention from Sukhdev Raj. The subsequent actions are described differently in Prakashwati and Yashpal’s accounts. According to Prakashvati, Bhagwati Charan Vohra noticed her discomfort and arranged for her to stay with Shrikrishan Suri’s family in Delhi. On the other hand, Yashpal states that he personally took on the responsibility of relocating her to a secure place. He further asserts that Vohra was suspicious of the behavioural code of conduct of Prakashwati and termed that responsible for offensive arguments of fellow comrades. If the latter view is accepted, one finds a representation of the popular notion in which women are considered responsible for any inappropriate action done to them by men.

Intense tensions arose within the party due to Yashpal and Prakashvati’s relationship, after they both worked at a bomb factory, According to both of their accounts, the chemicals used in bomb preparation released toxic fumes, requiring them to spend time outdoors for fresh air. Additionally, handling bomb ingredients made their hands unsuitable for cooking, leading to frequent meals outside. Fellow members perceived this as Yashpal prioritising his love for luxury over the party’s greater cause. Chandrashekhar Azad, highly respected in both accounts, allegedly ordered Yashpal’s execution for deviating from party rules. However, Yashpal somehow came to know about it from a fellow comrade and managed to explain his position to Azad. Azad is stated to have understood his position. Both of them view Azad not as an intentional guilty of the event, but a victim of the conspiracy of others. This episode sheds light on prevalent beliefs of the time, where constant scrutiny of women’s sexuality was deemed necessary. Prakashvati faced not only threats from fellow comrades but also constant surveillance of her character.

This article explored gender perceptions among HSRA revolutionaries. HSRA, as a whole, cannot be viewed as a homogeneous unit; as in every organisation, different members adopt different behaviour towards fellow members. We observe that while some members were totally conservative in their outlook, some were flexible enough to change themselves with the advent of new ideas. Regarding women’s inclusion in revolutionary groups, Loomba’s argument that women had to carve out their space, rather than organisations being inherently welcoming, has merit. It is essential to note that considering the societal conditions of that era, the recruitment of women into revolutionary organisations can still be seen as a revolutionary development. However, drawing definitive conclusions from available sources is challenging because most were written years after independence, potentially influenced by the prevailing notions of that time.