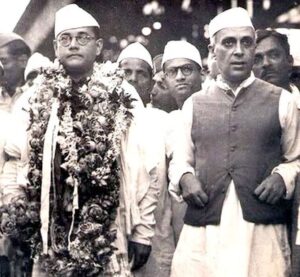

The Azad Hind Fauj, also known as the Indian National Army (INA), played a crucial role in India’s fight for independence. Formed during World War II, it symbolised India’s resistance against British colonial rule and showcased the strong patriotic spirit of the Indian people. Led by the charismatic Subhas Chandra Bose, the Azad Hind Fauj aimed to free India from British control and played a significant part in India’s journey towards self-rule.

Azad Hind Fauj was a part of Azad Hind Sarkar, the provisional government of India led initially by Raj Bihari Bose and later by Subhash Chandra Bose. Azad Hind Sarkar and Fauj propagated their cause and lighted the flames of patriotism through a number of songs, speeches, slogans amongst others. This article picks up some of the songs written by the members of Azad Hind Fauj at the time when it was active and tries to understand the values these songs imbibe.

The very first song to be considered is the community anthem or Qaumi Tarana of Azad Hind Sarkar. The song is an adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana in terms of its poetic scheme and lyrics at some places. However, to view it as a literal translation of Jana Gana Mana will not be appropriate. The song is written in a very simple language known as Hindustani spoken at that time by a great majority of the population. One can note a clear presence of a balanced use of Sanskrit and Persian words in the song which makes it linguistically inclusive. One example should serve to illustrate the point. One of the verses of the song reads, “sab ke dil main preet bada hai, teri mithi vani; har sube ke rehne wale, har mazhab ke prani”. While the words, prani and vani are Sanskrit driven, Persian taste is visible in ‘sube’ and ‘mahzab. While we cannot say that the exact number of Persian and Sanskrit terms is the same, there is a balance between these two linguistic registers throughout. None seems to dominate the other. Use of such a hybrid language may be evaluated under the context in which the song was composed in the year 1943. There was a rise of religious exclusivism in the country with two major religions: Hinduism and Islam viewing each other as very distinct from each other. It is possible that the song was written with a secondary, if not primary intention, of countering this spirit of antagonism by connecting people from different religions by one language.

The very first song to be considered is the community anthem or Qaumi Tarana of Azad Hind Sarkar. The song is an adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana in terms of its poetic scheme and lyrics at some places. However, to view it as a literal translation of Jana Gana Mana will not be appropriate. The song is written in a very simple language known as Hindustani spoken at that time by a great majority of the population. One can note a clear presence of a balanced use of Sanskrit and Persian words in the song which makes it linguistically inclusive. One example should serve to illustrate the point. One of the verses of the song reads, “sab ke dil main preet bada hai, teri mithi vani; har sube ke rehne wale, har mazhab ke prani”. While the words, prani and vani are Sanskrit driven, Persian taste is visible in ‘sube’ and ‘mahzab. While we cannot say that the exact number of Persian and Sanskrit terms is the same, there is a balance between these two linguistic registers throughout. None seems to dominate the other. Use of such a hybrid language may be evaluated under the context in which the song was composed in the year 1943. There was a rise of religious exclusivism in the country with two major religions: Hinduism and Islam viewing each other as very distinct from each other. It is possible that the song was written with a secondary, if not primary intention, of countering this spirit of antagonism by connecting people from different religions by one language.

The argument made above may seem a pure conjecture on its own, but it does hold strength if viewed in conjunction with other activities of the Azad Hind Fauj and Sarkar hinting at a secular approach. Though, it would be out of topic to discuss these activities in detail in this article, we can give a brief mention of these actions. Firstly, unlike a communal organisation of the British Indian army, Azad Hind Fauj was organised into Gandhi Brigade, Nehru Brigade, Azad Brigade, Subhash Brigade, and Rani of Jhansi regiment, all named on the most popular leaders than any community. Secondly, many of the close associates of Bose were Muslims such as Captain Abid Husain. Thirdly, Bose also glorified the revolt of 1857 for its unity of Hindus and Muslims. If the language of the Qaumi Tarana is understood in relation to these activities, we find that there is ample weightage in the argument that language could be a medium of religious harmony.

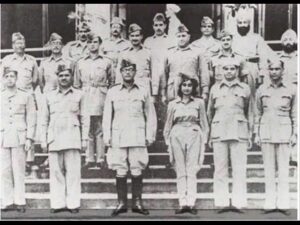

The next song taken for consideration exemplifies the gender egalitarianism of Azad Hind Fauj. It was an unprecedented act of the Fauj to grant military rights to women under a separate contingent called the Rani of Jhansi regiment. Captain Lakshmi Saigal recounts in one of her interviews that it was truly a revolutionary step to start a female contingent which was trained under equal discipline and strictness as that of men and more revolutionary is the fact that nearly 1500 women from ordinary Indian families joined the army. There’s a song dedicated to this female regiment written by Baldev Singh and music given by Captain Ram Singh. The song is titled ‘Ham Bharat ki beti hain’ (we are the daughters of India’). The beginning lines of the song celebrate the act of women taking swords in favour of their nation. The first stanza traces back the tradition of women involved in military activities to the ‘great tradition of Indian history’ manifested by the Kshatranis. The second stanza reinforces the boldness of Indian women by presenting analogies with mythological goddess Kali who is portrayed as a warrior quenching her thirst with the blood of devils. The third and the last stanza displays a spirit of fighting till the last drop of blood in the body. Prior to that, women had also been involved in military activities, but their role was primarily limited to being a cover for revolutionary activities of men. Additionally, women could create a safe space for themselves only in the absence of male counterparts. Such an equal role given to women was indeed unprecedented and the song resonates with that spirit.

The next song taken for consideration exemplifies the gender egalitarianism of Azad Hind Fauj. It was an unprecedented act of the Fauj to grant military rights to women under a separate contingent called the Rani of Jhansi regiment. Captain Lakshmi Saigal recounts in one of her interviews that it was truly a revolutionary step to start a female contingent which was trained under equal discipline and strictness as that of men and more revolutionary is the fact that nearly 1500 women from ordinary Indian families joined the army. There’s a song dedicated to this female regiment written by Baldev Singh and music given by Captain Ram Singh. The song is titled ‘Ham Bharat ki beti hain’ (we are the daughters of India’). The beginning lines of the song celebrate the act of women taking swords in favour of their nation. The first stanza traces back the tradition of women involved in military activities to the ‘great tradition of Indian history’ manifested by the Kshatranis. The second stanza reinforces the boldness of Indian women by presenting analogies with mythological goddess Kali who is portrayed as a warrior quenching her thirst with the blood of devils. The third and the last stanza displays a spirit of fighting till the last drop of blood in the body. Prior to that, women had also been involved in military activities, but their role was primarily limited to being a cover for revolutionary activities of men. Additionally, women could create a safe space for themselves only in the absence of male counterparts. Such an equal role given to women was indeed unprecedented and the song resonates with that spirit.

The final song chosen here is a Qawwali, a group song commemorating the activities of INA and hailing the leadership of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. Two aspects are recounted in this song. First of all, there is an attempt at recording the past of the Fauj through the voice of soldiers. The first stanza recollects that immediately after receiving the message of Netaji, the soldiers got inspired to raise the slogan of ‘jai hind’ (hail India) and take the tricolour to fight for the nation. The second stanza celebrates that despite facing many struggles, fighting starvation and thirst, they continued ahead without even thinking of looking back. The third stanza recounts the fact that Indians understood the true meaning of independence and brothers recognised each other. The reference of brothers recognising each other perhaps emphasises the event of soldiers of the British Indian army joining the Azad Hind Fauj. In the fourth stanza, the voice of soldiers states that they don’t care about millions of enemies that they have since they have the support of Netaji in their path towards freedom.

The second aspect of the song underscores the unshakable trust in the leadership of the INA. This trust is initially depicted through a recounting of the glorious history of the INA, where references to their inspirational journey can be found. However, it becomes most apparent in the final stanza, where the presence of Netaji is portrayed as a source of strength, dismissing any doubts or concerns among the INA members, as reflected in the lyrics- “vo lakh humare dushman hain par uski hame parvah nahi; netaji ke sahare se azaadi ka daman tham lia”. The song might have been written in the final days of Fauj when the battle seemed a bit hard. It seeks to reinfuse the spirit of patriotism amongst its members.

We see how cultural symbols like songs may reveal some of the important values of an organisation. While recollecting history from songs, it is however important to note that songs often exaggerate their concern and their words must not be taken as ‘objective’ facts. It is always useful to corroborate history from songs with a side-by-side reading of other sources too.