During the Raj, the British hosted three large ceremonial durbars in Delhi. The first was held in 1877 to proclaim Queen Victoria Empress of India. The second, in 1903, declared her son King Edward VII to be King Emperor. The third, in 1911, proclaimed King George V; and both the King and his consort, Queen Mary, attended in person, marking the first visit to India by a ruling British monarch. The pomp and ceremony of these celebrations were lavish in order to demonstrate the Raj’s majesty and authority, as well as the loyalty of well-known Indian subjects such as Maharajas and Nawabs of the Princely States.

Delhi as a previous chair of political power acted as a source of legitimacy for the founding of the British Empire in India. To assimilate with their subjects Britishers not only took the practice of holding durbars from Indian rulers but at the same time took its nomenclature. The display of power and show associated with these ceremonial durbars helped facilitate to ground the might and authority of the empire.

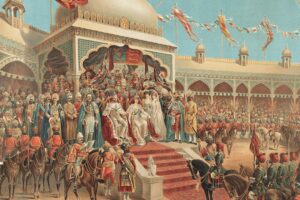

1877 Delhi Durbar

Thousands of attendees and festivities that lasted for two weeks – the first Delhi durbar in 1877 was organized by lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India and representative of the crown. Queen Victoria did not attend the ceremony in person yet it was a major watershed event in the history of Raj. Over 400 rulers, including 63 princes, attended the occasion. The princes marched by to salute the empress’ emissary, each carrying a silk banner specially created for the occasion. Each prince followed a carefully crafted hierarchy of importance. Many maharajas, rajas, and princes rode by on elephants laden with jewel-encrusted trappings. On the British side, the viceroy’s platform was surrounded by a large canopy, the poles of which featured British insignia such as the cross of Saint George and the Union Jack flag. A large gilt-framed painting of Queen Victoria, autographed by the emperor herself, hung over the seated viceroy.

The presence of 15,000 soldiers resplendent in their symbol red coats demonstrated the empire’s very genuine military power. All British officers and dignitaries wore their finest uniforms, with rows of medals gleaming in the sunlight and plumed caps swaying in the breeze. Another essential goal of the durbar was to demonstrate the unity of the new India – at least among its ruling elite – and it succeeded in this.

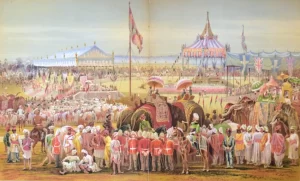

The 1903 Delhi Durbar

This durbar was held on January 1, 1903, to commemorate the succession to the throne of Edward VII, Queen Victoria’s eldest son and the first Emperor of India. Again, the monarch did not attend in person, most likely because Edward was 62 at the time.

Viceroy Lord Curzon (in office 1899-1905) officially represented the emperor. Curzon believed in the power of pageantry; thus, this durbar was even more impressive than the last one. Curzon intended to show continuity between India’s past and present-day British India, thus he included several historical aspects in the durbar. There were exhibitions of magnificent carpets, diamonds, gold and silverware, and fine paintings manufactured in India. All of these processions were mostly held in silence, which could indicate that Curzon was staging the event for the benefit of viewers of pictures and silent films. The new system of electric lighting constructed by the viceroy aided those catching the event on film.

The durbar, the subcontinent’s first filmed event, was played at cinemas in Britain and across India as part of news breaks between feature films. The durbar undoubtedly served to persuade the populace that the British Raj was based on mutual respect and consent, even if this was far from the entire picture of colonial rule in India.

There were critics of the event who called the durbar not a festival of coronation but a “curzonation”. The high costs of the celebration two years after a terrible famine in India brought Curzon under scrutiny.

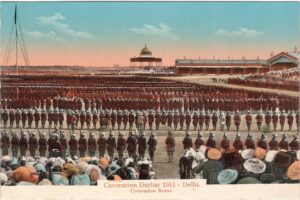

The 1911 Delhi Durbar

This durbar, held on December 12, 1911, was much more remarkable than its predecessors since the emperor was present in person for the first time.

Many Indian monarchs were bestowed with titles and participation in knightly organizations prior to the great event, maybe to assure goodwill and, more crucially, attendance. Such medals and accolades could then be proudly displayed during the traditional procession of respect to the British Crown. The king and queen were seated on a high crimson stage with a golden awning. The royal couple were dazzling in their purple and ermine robes and jeweled crowns, visible to all 100,000 attendees. Speeches were handed out in English and Urdu, and 30,000 troops marched past their king after a royal cannon salute. The durbar thrilled George V, who characterized it as “the most wonderful and beautiful sight I ever saw.”

The 1911 Durbar was also the occasion to announce two important administrative changes. The first announcement was the reversal of the controversial policy to partition Bengal and the second was the official change of capital from Calcutta to Delhi.

While several princes and princesses came to pay their homage to the new King and Queen of the Indian motherland, the Gaekwar of Baroda, Maharaja Sayajirao III, gave rise to a certain controversy. He arrived at the coronation, removed all his jewellery and left while showing them his back after one single and a simple bow. At the time, Sayajirao’s actions were considered to be a dissent towards British rule.