Satire is an artistic expression that uses humour, irony, ridicule or exaggeration to criticise and mock individuals, institutions or societal issues—tracing its origin from a Latin word, “satur”, which means “full” or sated. It was used to describe a poetic form that was a mixture of various elements like prose, verse, dialogue and monologue. Samuel Johnson, an English lexicographer, has described satire as “a poem in which wickedness or folly is censured” and more elaborate definitions are rarely more satisfactory. It can be traced from as early as the 7th century BCE when satirical works profoundly affected people.

The mention of satire in India can be seen in various ancient Sanskrit texts and epics. Maha Subhasita Samgraha, a compilation of Sanskrit proverbs and parables, is an exciting verse describing a whimsical conversation between god Shiva and goddess Parvati. Epics like Ramayana and the Mahabharata mention characters like Hanumana and Vidura, known for their clever wit and humorous commentaries. Panchatantra is one of the best examples of Indian satire. Over time, satire has become a powerful tool for making fun of politics and pushing back against those in charge. This becomes clear when we look at how people used satire to criticise religious rules and hypocrisy, especially those who followed the Bhakti and Sufism traditions with the purpose of challenging the dominant norms set by the Brahmin class in society. Instead of just being funny, satire was used cleverly to question and change how things were.

During the nineteenth century, India saw changes in its political situation along with social conditions, the growth of nationalism and modernisation in India. This was followed by the development of print culture in newspapers, periodicals, and magazines in English, Hindi, Bengali and other vernacular languages. Representation of visual thoughts and political cartoons was a medium of satirical presentations of the contemporary situation within the country.

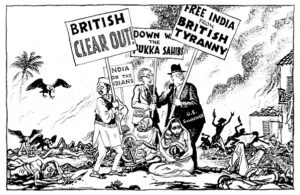

Functioning as “an instrument of societal critique”, satire frequently manifested within the pages of newspapers and periodicals, occupying a notable position within freedom fighters’ communication tactics. Eminent caricaturists like K. Shankar Pillai leveraged their artistic expertise to deride British policies and governing figures. The recurrent portrayal of “Uncle Sam,” a persona recurrently featured in Pillai’s caricatures, assumed the role of a representative emblem of the ordinary Indian, thus facilitating readers’ engagement with the satirical discourse encompassing diverse facets of colonial administration. These visual representations transcended the realm of mere aesthetic diversion, proficiently channelling the collective discontent and exasperation of the populace, thereby catalysing the sentiment of dissent. The domain of literature likewise welcomed the incorporation of satire as a method to underscore the incongruities inherent in British colonialism. A notable illustration of this phenomenon emerges from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s composition, “Vande Mataram”. This poetic creation, ostensibly a devotionally imbued hymn, adeptly harnesses cutting sarcasm to underscore the juxtaposition between India’s wealthy cultural legacy and the stifling yoke of colonial dominion. Chattopadhyay’s adroit employment of satirical elements inculcated a prevailing sentiment of patriotic ardour, exhorting readers to cast off the fetters of foreign subjugation.

The influence of the ‘railway’ on political economy and culture was also conveyed through various satirical cartoons and can be used to understand the impact of colonial technology. These cartoons often portrayed a satirical critique of railways, a theme common in periodicals during the 19th century, both in England and North India. However, the same technological advancement evoked contrasting reactions due to distinct historical and cultural contexts. One such cartoon titled ‘Hindustani relgari ka tisra darja’ (The Third Class of Indian Railways) illustrates the challenges of travelling, particularly for women who experience inconvenience. The cartoon depicts a scene where an overcrowded third-class train compartment is shown, with an Indian railway guard kicking passengers. Amid the chaos, men manage to board the train, but a woman has fallen onto the platform due to a stampede. An additional instance, illustrated through ‘Hamare relve stesan ka drishya’ (An Observation at Our Railway Stations), portrays Hindu women from a socially esteemed middle-class background waiting at the railway station. Meanwhile, men inside the train and on the platform cast inappropriate and lecherous gazes at them. The accompanying caption beneath the illustration distinctly reveals the patriarchal unease, stating “The presence of unveiled women at the station is akin to a sudden thunderbolt. This scene commonly captures the eager gaze directed towards them by railway officials, passengers, porters, and vendors alike”. The satirical critiques of railways offered from a Brahmanic male standpoint in India should not be mistaken as a wholesale rejection of the technology itself. These criticisms should not obscure the fact that most writers who employed satire to comment on railways held a profound acknowledgement not only for the advancement of railways facilitated by the British administration but also for technology and scientific expertise as promising avenues for the nation’s advancement. Yet, these instances should also be interpreted as reflections of the real-life circumstances experienced by marginalised Indians during that time.

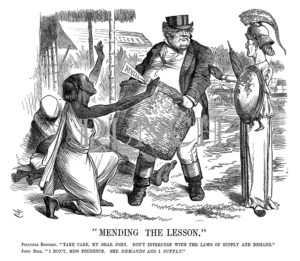

The Hindu Punch, a serio-comic publication, emerged in the latter half of the 19th century. Like its English counterpart, this magazine used satire to reflect everyday life, employing caricatures to depict Indian perspectives and positioning itself as a “foremost publication for promoting political awareness through humour”. An example of such a cartoon, “To The Relief”, was featured in Punch Magazine during the eighth Indian National Congress session in 1892. This illustration vividly portrays how British colonial governance siphoned resources from India through exorbitant taxation and the exploitation of raw materials. A soldier from the Indian Army is seen riding atop an Indian elephant, which is burdened with an array of weaponry, cannons, and firearms. The elephant’s feet are shackled to salt and land taxes and various legislative measures strategically designed to ensure the relentless exploitation of India’s natural resources, including timber. This cartoon emerged at a juncture when Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian Member of Parliament in the House of Commons, held the presidency of the Indian National Congress. Such satirical cartoons were purposefully crafted to enlighten the public on the exploitative aspects of British rule in India.

Distinguished luminaries within the ambit of the freedom movement astutely acknowledged the potency inherent in satire to captivate the populace and adeptly communicate their ideology. The periodical, Harijan, overseen by the venerable Mahatma Gandhi, regularly accommodated satirical compositions designed to lay bare prevailing social injustices, the dissembling conduct of the ruling establishment, and the imperative for transformative action. Through this amalgamation of humour and persuasive discourse, Gandhi deftly obtained a substantial readership to align with his overarching vision and cause.

The legacy of satirical defiance endured beyond India’s acquisition of sovereignty. The political cartoonist, R.K. Laxman preserved this tradition, using his visual compositions to cast a satirical lens upon prevailing political circumstances and societal quandaries. Central to his oeuvre, the image of “The Common Man” encapsulated the struggles faced by the ordinary Indian amidst the complexities of the nascent independent nation. Laxman’s caricatures consistently upheld the essence of satire as an instrument for scrutinising authoritative structures and cultivating responsibility.

Satire, a device for societal examination and interpretive discourse, was pivotal in India’s endeavour to break free from colonial subjugation. Operating through various mediums such as cartoons, literary works, theatrical performances, and the articulated expressions of freedom advocates, satire emerged as an influential tool in revealing the inadequacies and imbalances propagated by the British administration. By applying the forces of humour and sharpness, satire not only highlighted the contradictions intrinsic to colonial dynamics but also employed the potential to invigorate the masses, kindling a collective ethos of opposition and unity that ultimately played a pivotal role in the realisation of India’s triumphant quest for autonomy.

Shruti Sharma

Shruti Sharma, a History graduate from Indraprastha College for Women. Her area of interest mainly lies with historical research, and inter-disciplinary research. Apart from this, she is really enthusiastic about visiting monuments and unexplored sites in Delhi.