“What the typical Indian woman wants in her hour of trial is the thing to which she is historically used- the midwife- the dhai.”

-Katherine Mayo (Mother India, 1927, pp.91)

Over the course of several decades, familial, societal, and state mechanisms have been employed to manipulate and regulate women’s bodies to govern and facilitate their reproductive capabilities. Women’s bodies have not only been emblematic of societal honour but also served as a demarcation between the “us” and the “other.” These intricate connections between women’s bodies, caste and religious distinctions have given rise to a dichotomy of “otherness” and hierarchical power dynamics among women. Body politics, in the Indian context, has frequently manifested itself through the lens of caste. On one hand, women from upper castes find themselves entangled in gendered constructs, while women from lower castes experience the gendered construction of their bodies shaped by factors such as poverty, malnutrition, labour, and various other circumstances. Their bodies are often depicted as degrading, contaminating, unclean, and impure. Nonetheless, both categories of bodies are subjected to exploitation within the framework of capitalistic and patriarchal power structures. Simultaneously, the medical community has wielded significant authority over women’s bodies and labour. This phenomenon can be comprehended in relation to the shifting role of “dhai” in Indian society during the colonial period.

For ages, Dais have been primarily concerned with managing the woman’s body before, during and after pregnancy. They serve a vital role for women in terms of cultural competency, consolation, empathy, and psychological support during pregnancy, labour pain, and postpartum depression, with advantages for both the mother and the child. The historical mistreatment of midwives can be traced back to as early as the thirteenth century when medicine was evolving into a secular science. Women were often accused of witchcraft by the emerging male dominated biomedical establishments. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, midwives were considered a societal threat. These negative perceptions of Dais and native delivery practices had a significant impact on South Asian colonies, further stigmatising Dais. The general perception prevalent in Indian society, particularly of the elite class and upper-caste during colonial era about the whole process of birth-giving and the status of dais revolved around their purportedly ‘dirty habits’, lack of formal training and the unhygienic condition of childbirth. This image of the filthy midwife was based on a complex set of social and cultural assumptions that were constructed and maintained by the ruling classes. The shift in position of midwives during the colonial era could be best understood by a case study of Bengal.

The historical significance of woman-oriented midwifery in Bengal is evident in the region’s lag behind Madras in institutionalising midwifery during the 19th century, despite Bengal’s prominence in the British imperial context. In the early 20th century, dais were accorded the revered title of “dai-ma” and held high social prestige. However, their esteemed status began to erode due to neglect and derecognition by modern medicine, heavily influenced by colonial practices. Notably, the Calcutta Medical College took steps to include midwifery in its curriculum in 1841, establishing separate professorship in anatomy and midwifery in 1849, signifying a significant shift in the practice of childbirth. The medicalisation of childbirth was preceded by the formation of a medical discourse on midwifery, a process facilitated by the inclusion of midwifery in the medical curriculum. Due to its lacklustre job prospects, midwifery maintained a minor position in scientific medical education. Nonetheless, the fact that it was given its own professorship demonstrates that it was beginning to be recognised as a medical discipline. However, the British colonial state did not allow these trained midwives to function autonomously. They were asked to compromise with their demands as it was believed that they were undermining the two main goals for which the government had trained them: improving the lives of Indians in poverty and reducing the dominance of the traditional birth attendant, the Dai.

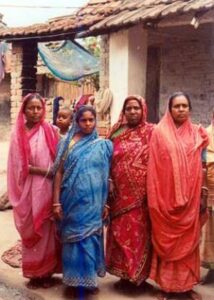

Midwifery, practised mainly by lower caste women, was the common method of childbirth. In a study conducted by Ceilia van Hollen, on traditional Dais in Tamil Nadu, it was observed that many Dias had ancestral ties to the barber castes and were involved in patron-client relationship or jajmani ties in the precolonial era (Van Hollen, “Birth on the Threshold”, 2003, pp.39). These women were primarily from the low-caste Hindu or impoverished Muslim backgrounds, passing down their knowledge through generations. However, during the 19th century, colonial and reformist discourses began criticising midwifery, associating it with India’s perceived decline in women’s status. This led to calls for reforms guided by colonial “scientific knowledge”. This could be best understood by implying David Arnold’s approach of the state centred system of scientific knowledge and power. This interplay between power and knowledge manifested itself in terms of double dose of restrictions received by midwives. In Indian society where women were barred from gaining literary and sacred knowledge; in such a scenario, midwife’s wisdom disturbed the divide between vidya (knowledge) and the body, between physical birth and the superior form of spiritual rebirth. Second, the knowledge of the midwife, as practical knowledge, stays beyond mainstream perceptions of what it means to “know” something.

The issues linked to midwifery were considered double sworded: no credits were given to the European art of obstetrics and the ignorance of these wretched dhais that caused several mishaps like the act of infanticides, failure of birthing practices and so on, remain unpunished. This was against the British conception of authority combining both power and the notion of ‘moral influence’ – the idea that the Raj was the ultimate definer of appropriate social behaviour. So, even though the issue of infanticide and abortion was not a direct threat to British power, it did not fit into their conception of morality and the very existence of these practices suggested the failure of colonial state. Thus, Dais who once stood at the crossroads of various strata of power, had their knowledge and wisdom of indigenous delivery practices devalued by the patriarchal system and the ever-growing propensity and faith in western medicine and healthcare. Dais’ unwritten traditional knowledge had little value in a culture that only recognises knowledge that has been documented. Moreover, colonial discourses frequently labelled the methods of Dais as barbaric and portrayed them as the main contributors to high rates of newborn and maternal mortality, obstructing the promised development by colonial authorities. This criticism of native birth practices undertaken by midwives or dhai was thus an attempt to establish gender, caste, and class hierarchies, as well as altering power and knowledge divisions.