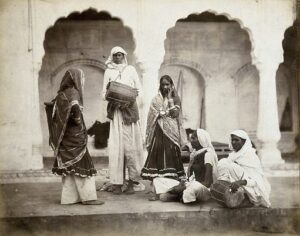

The word hijra is an Urdu word, originating from the Persian hiz, meaning effeminate. Usually assigned male at birth, hijras are usually categorized as trans-women. However, not all trans-women are hijras. The latter have their own elaborate traditions like initiation rituals and discipleship that defines their identity distinctly from the others. Hijras are male-born emasculates or “born eunuchs” who dress in feminine clothing, take feminine names, have traditionally blessed or cursed fertility through performances either in public or in households. Since their identity is different from the general binary identity of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, their acceptance within the societal fold has always been challenging, especially in the face of repressive exterminating policies adopted by the colonial government.

The beginning of anti-hijra legislation can be traced to the middle of 18th century with the death of Bhoorah, a hijra in Mainpuri district of the North-Western Provinces (NWP), her ‘head nearly severed’. The idea of hijra was not contiguous with the colonial idea of sexuality, and the death of Bhoorah provided the pretext to exterminate the hijra community from the subcontinent. The trial that followed found Ali Buksh, Bhoorah’s male lover guilty of murdering her, and at the same time criminalized hijras as “cross-dressers, ‘beggars’ and ‘unnatural prostitutes’”. The NWP government decided on a course to exterminate the eunuch community in their province. They argued that hijras kidnapped and castrated young boys to initiate them into the eunuch community, and hence the responsibility of ‘rescuing’ young boys from their clutches fell on the British government.

Thus began the colonial enterprise to regulate and restrict the hijra community in NWP to eventually perpetuate their extinction. While enough scholarship has been dedicated to studying the first part of the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871 (CTA), the second part, dealing with eunuchs, have remained relatively under-examined. Dealing with the ‘eunuch problem’ in the Criminal Tribes Act shows how the British administrators perceived an entire gender category to be ‘criminal’. It was a reflection of English immorality associated with non-binary gender expression. In fact, to this date, Britain does not recognize non-binary gender identity. Thus, the hijras posed a tremendous challenge to the colonial administration. The definition of a eunuch in the CTA was itself ambiguous. Eunuchs were understood as those “of the male sex who admit themselves, or on medical inspection clearly appear to be impotent”. Additionally, a register was required to be maintained recording “the names and residences of all eunuchs…who are reasonably suspected of kidnaping or castrating children” and committing offences under the now decriminalized Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The tradition of discipleship among the hijras implied that they lived together as a community in ghettoed colonies. Thus, another register, recording the property owned by those eunuchs ‘with criminal tendencies’ was also needed to be kept.

Hijras were traditionally engaged in both public and household performances for their livelihood. The colonial legislation struck right at their roji-roti. The police was empowered to arrest hijras “dressed or ornamented like a woman” engaged in any form of “public exhibition” including dance or music, from both public and private places without a warrant. They were also barred from adopting minor boys, as it was believed that hijras castrated young boys to initiate them into their community. Therefore, hijras could be arrested by police if minor boys were to be found their residence. Such boys, after they were rescued were needed to be sent off to their parents or guardians, and if they could not be traced, were to be left at the care of the administration. Thus, the project to eliminate hijras was a radical one, and not quite involving assimilation or banishment as had been suggested by many Indian commentators. Removing young boys from the hijra household meant that castration and initiation could no longer be performed. Registration of hijras would allow the authorities to restrict new initiations, thus resulting in the community eventually dying out. However, the hijras used the loopholes of the colonial system that tried to extirpate them to their self and culture alive to this day.

The vague and ambiguous definition of a eunuch in CTA created confusion as to who was a eunuch. Secondly, the presence of non-binary groups who were not part of the hijra community, like khwajasarais, masculine-embodied court officials and harem servants further complicated the matter. Therefore, feminine dress, performance, and gender expression constituted the metrics of identifying a eunuch. Additionally, medical knowledge became increasingly used in determining impotency. However, ineffective surveillance and the inefficiency within the police force was a major hindrance to the government’s efforts. Efforts from the hijras to escape the watchful eyes of the authorities included migrating to other British provinces or princely states, and putting on masculine dresses to evade arrest.

It was not only the government that was bent on exterminating the hijra community, but a major section of the Indian middle class too shared similar motivations. This middle class comprised mostly of English-educated intellectual men who shared similar notions of morality as their English masters. This reflected, as Jessica Hinchy argues, “the imbibing of colonial morality” and “shifting class dynamics in north Indian society”. This middle class, along the lines of the colonial stereotype, associated hijras with kidnapping and castration, and argued for the elimination of their immoral practices. However, unlike the British, the Indian intellectuals equated the discipleship within the hijra community as ‘slavery’, a term the British had cautiously avoided. Others considered the presence of hijras in public places as immoral and obscene, and argued for their ghettoization and restrictions on their mobility.

Thus, hijras were victims of marginalization for a long time, and the colonial endeavour to exterminate an entire gender group proved to be testing times for the physical and cultural identity of the hijras. Ingrained colonial morality in the educated middle class of the 19th century further perpetuated the otherization of the community. Although legally recognized by the government after Independence, hijras today live in both socially and economically challenging conditions, depending on performances and begging for their livelihood.

Sharanyo Basu

Sharanyo Basu is an undergraduate student of History at Presidency University, Kolkata. He is a history enthusiast with interests in social and cultural history, literature and films, and histories of interactions, conflicts and accomodations.