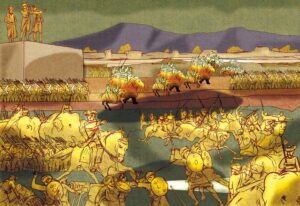

A sleepy Indian village on the eastern banks of the river Bhagirathi near Calcutta suddenly rose to prominence one day for it provided a turf. A turf that aided the clash of the Titans which historians believe changed the course of history of this nation. On 27th June 1757, this village Palasi (Anglicized version-Plassey) witnessed these Titans- the British East India Company led by Robert Clive and the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah engaging in a catastrophic war popularly known as the Battle of Plassey.

On the battleground the Nawab and the Company locked themselves in a series of attacks and counterattacks. And just when Clive thought he had lost due to cheating and treachery by the defectors, it started to rain! The British Company had got tarpaulins to cover their cannons and keep the ammunition dry but the Nawab had not. The Nawab relied heavily on his assumption. He assumed that the British ammunition would be wet and useless just like theirs. In that belief he ordered his army to storm. But as luck would have it Nawab’s cavalry was slaughtered, killing his chief Mir Madan too. In the end it was Clive’s dry artillery that claimed victory for the Company. This Battle of Plassey established the British East India Company as the new masters of Bengal and later the entire country. At this juncture a lay thought that crosses one’s mind is, “What if it had not rained that day? Would the history of India be different?” Well! One cannot say. We can only say that the Indian monsoon which has shaped the identity of this country since ages had just added another page in its history by bringing this brief spell of rain at Plassey.

Throughout history the Indian monsoon has had great linkages and held immense significance. If we were to analyze the literature compiled (Vedic Literature) during the period 1500–600 BCE (Vedic Period), it describes monsoons as the time of transition of the ancient pastoralists from nomadic to permanent settlers surviving on a rain fed agriculture. In his study of the “Frog Hymn” of Rig Veda, Sanskrit scholar Gautama Vajracharya found Indian seasons had an immense impact on the migration of the people during this period. India being largely based on an agrarian economy; rainfall is considered the life force of all agricultural productions and sustenance. Even foreign visitors have talked a lot about this in their written accounts. In his book ‘Indica’ the Greek historian Megasthenes who visited India in 4th Century BCE wrote about the double monsoon -one in summer and the other in winter that India gets each year and how these contribute to a double harvest, income, and eventually double prosperity (Crindle, 1921). He credited the monsoons for the large-scale wealth and prosperity India had achieved. Thus, the annual rainfall became the harbinger of abundance, earning India the sobriquet “Golden Bird”.

Along with Monsoon comes its inseparable part i.e., rain forecasting and prediction. Krishi Parashara is believed to be the first agricultural almanac that India had developed in the 4th century. Written in Sanskrit this text has many sayings pertaining to rainfall prediction based on planetary movements. (Sadhale, 1999). ‘Brihat Samhita’ written by 6th century mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Varahamihir explains seasonal rainfall prediction through lunar mansions or Nakshatra. He also discusses Hydrometeorology in three other chapters. The following excerpt from his book outlines the importance of planetary movements in rain forecasting.

“Which science is superior to this astrological science which determines the exact time of the rain, since by knowing this science alone one gets the power of visualizing the past, present and future, even in this kali age which destroys all good things (sloka 4)” (Sastri & Bhat, 1943)

When it came to interactions with the outside world the Indian monsoon, here, played its part too. This time it was the monsoon winds that boosted trade in the Indian Ocean. Trade routes by sea were already in operation since the beginning of the Common Era wherein India developed trade links with the Roman empire. The credit for this goes to the Greek navigator Hippalus who discovered the Indian monsoon winds or the trade winds. He studied these winds and understood it reversed twice a year thus helping him navigate his round trip from the Red Sea to India within the same year (Schoff, 1912). His sea exploration opened the way for more traders to venture out on this route. The same system functioned in the Bay of Bengal too which successfully helped establish trade links with Southeast Asia. There were prosperous maritime trade exchanges between Roman, Greek traders and the southern dynasties of Cholas, Pandyas and Cheras. These economic connections and cultural exchanges till the 9th century helped India etch her place in the international trade map. It was Al-Masudi the famous Arab climatologist of the 10th century who gave comprehensive details of the Indian Monsoons during his visit to India. Later Al-Balakhi developed the first climatic atlas of the world titled Kitabul-Ashkal using the climatic data of Al-Masudi and other Arab travelers (Tibbetts, 1971). If it wasn’t for the Indian monsoon winds the atlas would not have probably been made ever.

In the end one can only be at awe at the way rains or monsoon are entrenched in the social, economic, and cultural fabric of this country. Each era through time, the monsoons held an important place in the life of the people. From the ancient times to the modern one it has always heralded prosperity. Not just India, the Indian monsoons also contributed to the socio-economic and cultural development of the entire South Asia. It strongly affected the climate and water resources of this region which in turn impacted the foodgrain production of nearly a quarter of the global human population living in South Asia. That’s what the Indian Monsoon is capable of. Can we not call this carving of an identity and that too a unique one?

Bincy Thomas

Bincy was a teacher by profession but now, is a history buff by choice. Being a fitness enthusiast with a keen interest for trekking, she combines this interest with history and sets out exploring lost and forgotten monuments, to gather new insights and information. When she’s not trekking, yoga, meditation and reading takes away her time.