In Bihar, most planters were British. When the demand for the blue dye outstripped supply in the early 19th century, the East India Company had turned a blind eye to the arrival of certain French, Italian, and Portuguese immigrants. Yet after that, it was obvious that entry was restricted. The plantation sector in colonial India offered young British applicants career opportunities. They mainly came from the middle and upper middle class of British society. The colonial administration too encouraged the entrepreneurs back home to set up indigo plantations in Bengal and provided them with capital.

The indigo tracts encompassed different forms of land tenure. The native thikedars and zamindars had a special relationship with the British planters. They were mostly from the upper castes. The thikedars who were the owners of very large holdings, sold the thike (lease) of their land to the planters for several years on a fixed term. Even in the areas where individuals grew indigo, the rent was extracted by the zamindar from the planters as it was conventionally entitled and along with it also came the traditional coercion rights to the planters.

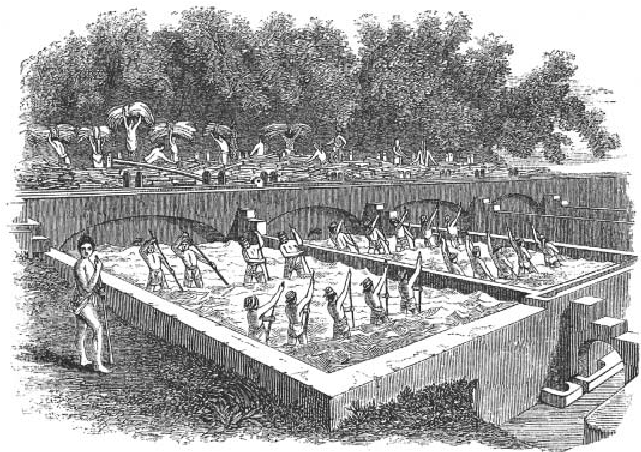

There were two types of indigo cultivation. The native landed class worked as either contract farmers for the planter or as wageworkers which was the ryoti or raiyiti cultivation. The system where the planters hired labour to manufacture indigo by leasing land from the zamindar under his direct control was the Nij cultivation.

Bengal became the epicentre of indigo manufacturing in the third quarter of eighteenth century and Lower Bengal was the heart of indigo industry at this time. Around the same time indigo manufacturing also began in the four districts of Bihar, Muzaffarpur, Darbhanga, Saran, and Champaran.

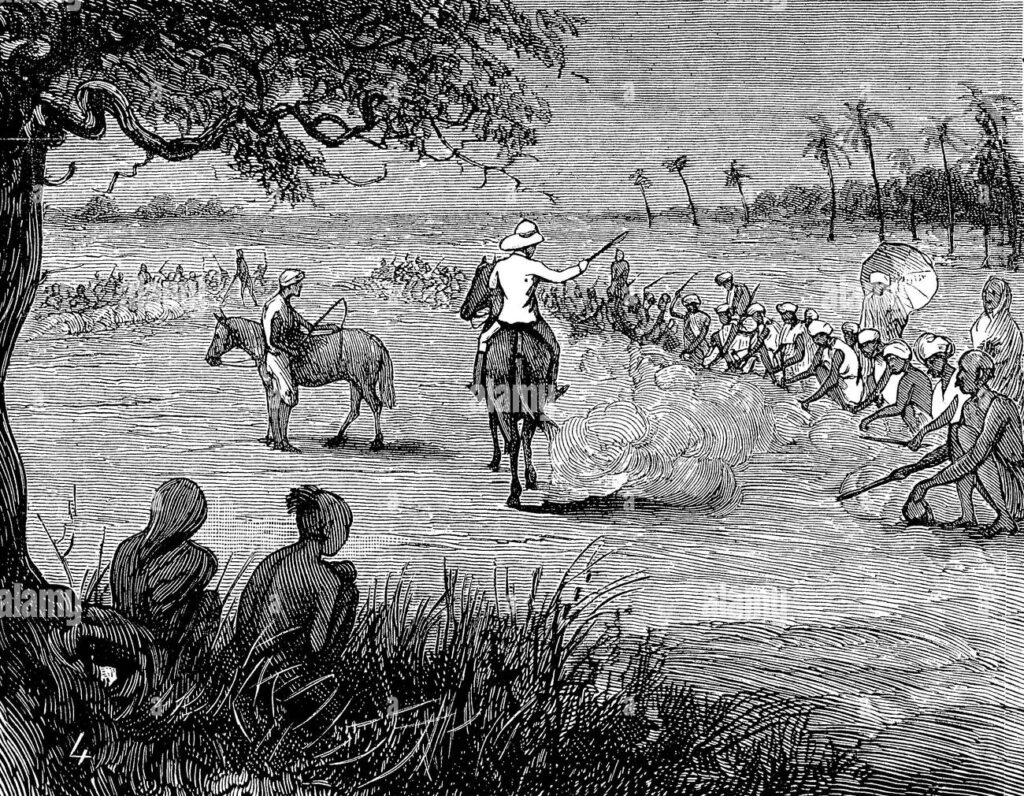

In rural India, there were numerous large-scale British plantations that had neither a military nor a religious purpose. Their mode of operation was distinguished by a regular use of coercion, which is supported by a wealth of evidence. To force indigo on cultivators and keep them bound in the system for as long as possible, the planter used coercion. Both legal and illegal forces were utilised for exploitation, including 1) to extract the best land and labours for indigo; 2) to pay the lowest possible price for output; 3) to impose all risks of crop failure on the cultivator; 4) to invoke assumed zamindari rights for underpaying or not paying cultivators for supporting services; 5) to impose improper measuring and weighing systems for land and produce; 6) to impose ahbabs (customary payments) on cultivators and 7) to extract dasturi (bribes) for factory servants.

For the first time in the history of Indian agriculture, the cropping pattern choice was taken away from the cultivators and economies worked against the cultivators. The apparently innocent ryoti method of indigo production was constructed through several different techniques of coercion. Sometimes, the advance given by the planter to the peasant was not enough and the peasant had to supply all other means of cultivation and bore the risks too on their own. If the indigo failed, the peasants were indebted to the planters. After that it was extremely difficult for the peasants to get out of their contract with the indigo planters. If the cultivator failed to pay the advances at the end of the cultivating season, the planter still gave him money for fresh planting in the next season although the debt kept on accumulating. The contract to grow indigo passed down from generation to generation keeping the peasant families obligated to grow indigo. The manufacturer also resorted to force the contract upon peasants and manipulated the advances and the account books to reduce them to the position of debt-bondage and force them to produce indigo in perpetuity. Those who refused were subjected to physical abuse. Violence against peasants took various forms like taking away land, labour and cattle, abducting, illegal detention, and corporal punishment. They also kept lathiyals or armed men.

Raiyati was still the planters’ favourite method of handling indigo cultivation. This kind of cultivation included a significant amount of unpaid work, which the planters found useful. Low indigo prices did not fully compensate the peasants for the labour requirements of planting, cultivating, and shipping the crop. The only reason the peasants could manage this burden was because they made use of the repertoire of “free” familial labour for indigo. On three-quarters of their land, they could grow crops that would feed their families. Moreover, planters used a range of illegal tactics to keep control of the raiyati system over the peasantry. And colonial administrators lacked the political will and power to intervene at the local level to mitigate those ills. Planters’ larger concern was to protect the sanctity of contracts that they signed with peasants for cultivating indigo.

The planter-manufacturers initially lured the peasants by offering cash advances so they could cover their living expenses, pay taxes, or make investments in the following cycle of production. Peasants were in favour of indigo sowing if it took place on alluvial land that wasn’t being used for rice farming because it supplemented their income. Peasants, however, were resentful as production increased and encroached on territory that had previously been utilised for producing food grains. They stopped growing indigo because it was less economical than growing rice, especially when rice’s price was high, as it was in the 1850s.

What added to the misery of the peasants were the rising prices of agricultural produce in the 1850s and the lack of a corresponding increase in the price of the indigo they raised which later led to various peasant rebellions. The Indigo Rebellion of 1859-60 was a direct consequence of the exploitation by British indigo planters.