Describing him solely through his work would be unjust as there is more to clicking photographs and documenting them. This is how I felt after listening to John Isaac’s TEDx Talk “The Picture I

Didn’t Take”. A photojournalist, wildlife enthusiast, and guitarist during his free time, John Isaac provided a different perspective when narrating the pictures he never took while documenting war, conflict, refugees, and cleansing.

Born in Chennai, John Issacs’s trajectory to photojournalism wasn’t destined. Instead, his interest in folk songs around the 1960s led him to the United States. As quoted in his interviews, he ended at John F. Kennedy Airport with his “12-string guitar and 75 cents in the pockets”. Thus, he initiated his singing journey in the streets for sustenance.

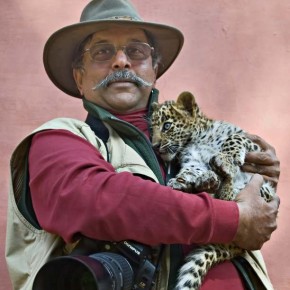

Source- Better Photography

During one of his sessions at Greenwich, he met a woman who worked at the UN and wanted him to audition for the UN singers. It led him to become a messenger, incepting a memorable association with the UN spanning more than three decades.

From winning an international photo contest to being apprenticed as a darkroom technician, Issacs’s journey as a photojournalist was gradual that concluded with his retirement as the Chief of the Photo Unit in 1998.

However, it is here that his journey remains distinct and significant as it forces us to question if the role of a photojournalist is only to capture and document situations of crisis and conflict or does it go beyond that. It was after winning a major award at Photokina in Germany (1978) that he was instructed by the UN to undertake an overseas assignment. It was the Israel-Lebanon conflict. Later he witnessed the Iranian Revolution, the 1984 Ethiopian famine, and Namibia’s independence. It was his second assignment to Vietnam during the 1970s that triggered a sense of queries regarding his responsibility as a photojournalist. He recounts how he saw a young girl staring at the ocean. People mentioned that her parents were killed and she had been raped by the pirates. Instead of taking a photo, he contacted three catholic nuns to provide her care. He was criticized for ‘not doing his job’ or ‘not being neutral’. Another incident was when he faced abuses by a cameraman for ruining his Pulitzer Prize by assisting a woman who had delivered amidst the Ethiopian famine. While he frequently dealt with such criticism, he also acknowledged that his photographs had also led to the international assistance of many including children refugees.

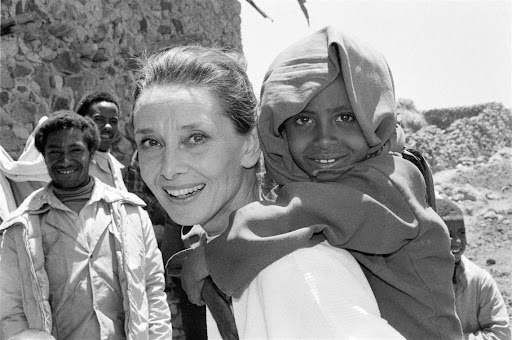

Source- UNICEF

Even while touring with Audrey Hepburn under the UN, UNHCR, and UNICEF he narrates the various times he didn’t click her photographs for they were ‘too intimate’ between her and the children. In one of the most prevalent photographs (attached) where she is holding a child, the American Photo asked Hepburn if they could airbrush her wrinkles to which she stated, “Johnny, tell them not to mess with that picture. I’ve earned every one of those wrinkles.”

The worst, however, arrived at the Rwandan Genocide in 1994 where the first-hand experience of ethnic cleansing, ravages of life, and his incapability of taking the child who looked at him as his father led to a ‘rude awakening’. His emotional involvement with his subjects made him quite distinguishable from other photojournalists which further led to a nervous breakdown. However, he never regretted the relations he cultivated as he credits his mother who emphasised protecting his dignity to protect other people’s dignity.

Source- Better Photography

With a short medical leave from the UN, he moved away from the camera. He reminisces it was a dark time with violent dreams to the extent of killing him. He rejuvenated his passions when he abruptly clicked 36 frames of a butterfly on a sunflower in his neighbour’s garden.

He would gradually switch to wildlife photography but also authored various books, including Children in Crisis (1996) which gave first-hand accounts of families and children in conflict regions. Other contributions include Endangered Peoples (1993) and Coorg, Land of the Kodavas (1995) with Jeannette Isaac.

In 2008, he co-authored a book, The Vale of Kashmir, about the people of Kashmir emphasising the necessity of maintaining peace. Photographing localities and landscapes without much editing intervention, he was able to photograph the tragedy and humanness Kashmir imbibed. While he experienced first-hand encounters with the army, he still captured glimpses of real-life amongst difficulties. From focusing on father-son relations to the Gujjar families living amongst the mountains, universality remained the main aspect. The series also includes the morning bazaar at the Dal Lake, people visiting Shalimar’s garden and a man looking from a window while being surrounded by pheran, and a series of unstitched clothes with traditional embroideries.

Working as a freelancer thus, became a new chapter in itself. From working on Indian tigers and birds to printing his works, thanks to his experience as a darkroom technician, John Isaac says that photojournalism has taught him composition. It is wildlife photography that made him patient and observant. He still believes he hasn’t clicked the photograph which is a result of his reading, listening, or seeing yet. While I patiently wait to witness it, he has put forward an important philosophy that needs to be imbibed upon, as his mother also emphasised, that we are primarily human beings, and then comes our “Job”.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your post seem to be running off the screen in Chrome. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design look great though! Hope you get the problem fixed soon. Cheers

whoah this blog is wonderful i like studying your articles. Stay up the good paintings! You recognize, lots of persons are looking round for this information, you can aid them greatly.