“Ignorantia juris non excusat.” – Ignorance of the law excuses not.

The ongoing era of the pandemic has been revelatory for India’s governing topography, pitting public interest right against the systems and mechanisms of governance. One after another, debates on common civil liberties, democratic processes, economic liberty, financial stability, administrative reasoning, and the predicaments of the judicial apparatus — all these factors came to the surface as the determinants of the public health crisis exacerbated the ways of life as we know them. Too many countries around the world took advantage of the once-in-a-century pandemic, taking to oft-arbitrary and authoritarian ways of decision-making. What the pandemic revealed the most in our country is the extant magnitude of uncertainty, not just among the society’s subaltern but also among those expected to maintain it in the presence of a full-blown health emergency.

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to cause increased levels of illiteracy among millions of children with the shutting down of physical academic institutions across the country, pushing a ten-year-old chart of progress to an irreversible curve of decline. With courts across the country shut before the masses, shifting to an exclusively virtual mode, the pre-existing backlog of cases in the judiciary was further marred by issues of inaccessibility. Furthermore, at least in the initial few days of the pandemic, the judicial focus seemed to digress from the immediate crisis at hand. In the days leading to Lockdown 3.0 in May 2020, the Supreme Court pronounced judgements in 73 cases, of which merely two were directly related to the exigencies arising from the pandemic.

This physical closure of schools, courts, places of commerce, and centres of rigorous intellectual and financial activity, has put an effective stopper on the broader marketplace of ideas. Inevitably, we’re bound to see a new crisis of thought, as the very mechanisms that are supposed to preserve the democratic ideals of the nation push it backwards to the dark vestibules of ignorance, the pandemic being just a good catalyst to the existing, unrecognised plague of illiteracy and indifference.

The crisis, today, is two-fold — one branching out from the judicial sphere and another from the rooms of common public policymaking. The adversarial means of mainstream adjudication followed in India is testament to the faith the country reposes in its people and their legal representatives to maintain the scales of justice as the established process takes its course. With a neutral adjudicator at the fulcrum of decision-making, the system allows the parties in the dispute an enhanced control over the dialogue and the outcome, as the case goes for most democratic setups across the world. Concisely put, justice through the mainstream means in India is premised upon the legal prowess vested in the hands of the disputants and the intellectual means by which it is pursued. These rationale hoist legal knowledge, not just of the advocates and representatives but also of the parties at real-time stake, and by and large, their understanding of their own cause, as the most important vehicle of justice and parity in the country.

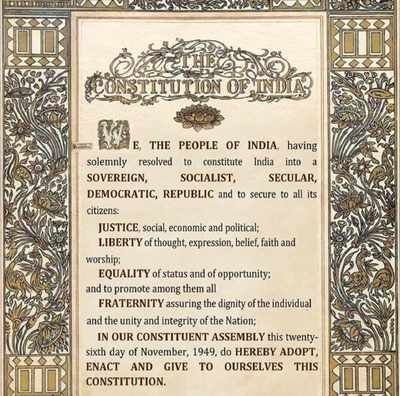

Even beyond the technical chassis of the courts of law and justice, the democratic courts of governance and policymaking call for an active participation of the common citizenry to ensure that the decisions in the legislative and executive order are in the most rightful public interest. If Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India upholds the right of free speech and expression, the right to free information, the right to know, the right to attain the stronghold of proper knowledge of facts, rules, the working processes, and the system itself, is enshrined under the same right by the principle of extended rationality. The right to be aware of the schematic design governing the country on all levels and for being an essential precept of civil liberty and awareness, especially in today’s testing times, one wonders if this right is instead an essential civilian duty to be aware of the technical processes. The answer is that it is both. Legal and political literacy in India is a part and parcel of its democratic spirit — the steering mechanisms prove so, and so does the current situation.

Beyond these reasons and backings, however, there is no denying that India, among a league of the many developing countries, cannot rationally afford to put the full weight of the system over a vastly unequal citizenry. In a country such as ours which, at least on paper, puts grave emphasis on rules, regulations, codes and processes, to the effect that the very ‘just end’ loses its essence beyond the multi-layered filters of procedural complexities, the common individual cannot be expected to defend themselves without the proper backing of the state itself.

It is the emergence of this contradiction between the imperative to safeguard democratic ideals across all three of the horizontal branches of the process and the attempt to elevate the citizen as the maker of its own destiny, that forms the spirit of state-led welfarism in India. A crucial element of India’s welfarist approach, as underlined in Article 38 of the Constitution as a part of the Directive Principles of State Policy, is to secure economic, social and political justice “informing all institutions of the national life”. Bridging gaps in terms of income and social equality is the means by which this justice can be sought effectively through the medium of resource redistribution as well as the provisions of universal basic healthcare and primary education, two broad avenues that are also the most pertinent spheres of policymaking in the country. For the latter, in particular, a wide range of political commitments and schemes have been introduced with varied rates of success. However, literacy in general has often been seen to stagger and wriggle at a pace that is undesirably sluggish and unproductive.

Literacy, as defined by the National Literacy Mission in India, entails the acquisition of basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills and the ability to apply them on a day-to-day basis, identifying the “causes of deprivation” and to overcome them with a continuous “participation in the process of development” along with the imbibing of values of common national and social interest, among others. The formal governing codes implicitly mandate that basic legal literacy also be a part of this holistic definitional umbrella. However, far from being a part of these comprehensive definitions, India’s average literacy rate — a term which is defined as the number of citizens above the age of 7 with a grasp over the most basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills — stood at a mere 73% as per the Census of India 2011. The 2011 census also revealed a slowing of the decadal growth rate when it came to this literacy rate and projected a time span of another 50 years for India to reach universal literacy, as per the terms of this basic definition. The numbers among women, socially and economically disadvantaged sections, as well as rural areas have been found to be exceptionally low, vis-a-vis the urban middle-class demographic.

One can only imagine the status of some higher, technically-advanced continuum when it comes to basic legal awareness in India in light of these numbers in the context of general literacy alone. Most often, legal knowledge in India is considered as the stronghold of lawyers and juristic experts, far removed from day-to-day society. It is by virtue of this universal belief and isolation from the legal system that the common citizen often finds themselves lost on the pathways of justice amid the venerated procedures ‘established by the law’. Thus, maximum legal literacy is the foremost criterion upon which the realisation of the citizen’s fundamental human rights stands. This also holds relevance from the liberal point of view in pursuit of a decentralised and democratised regime of governance.

Each year, the month of November stands as a tall reminder to the grandeur of the Indian legal system, in it lying not just historicised occasions celebrating the ideals on which it was founded, but also the introspective spirit that recognised the need to extend it to the masses. These two occasions, including the enactment day of the Constitution of India, also known as the Constitution Day marked on November 26, and the Legal Services Day, observed on November 9, make the law of the land potent of entrenching India’s grassroots and flourishing its grounds with the verdure of constitutional duty.

The Legal Services Day, commemorating the enactment of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, is of significance in order to ensure the implementation of the ideals of free legal aid, under Article 39A, to “establish a nationwide uniform network for providing free and competent legal services to the weaker sections of the society on the basis of equal opportunity,” as also to direct attention to the tenets of “complete and tangible justice” under Article 142. Justice, it was realised, should not only be done but also “seen to be done”, as a part of the implicit objective of this Act. It established authorities for legal services across the country, including the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) and the various state, district and taluk units, alongside distinct authorities for the Supreme Court and the various High Courts to lay down proper policies and principles in pursuit of universal legal aid in the country.

A crucial part of this campaign was the National Legal Literacy Mission, formulated by the NALSA in 2005 for a five-year term to “take the law to the masses” and impart awareness and education related to legal rights and services under the Act. The Mission also set out to prepare state-specific plans of action, undertake social audits and sensitise judicial officers on issues of public interest, as a part of its broad agenda. Several legal literacy programmes, campaigns involving law students, along with legal literacy clubs and walks touching upon various aspects of the law, were launched in educational institutions across the country in 2010. The screening of documentary films and the use of folk media, including street theatre and community radio programmes, were also widely implemented with the broad goal of ensuring maximum local participation and engagement in the campaign.

However, this mission also seems to have wriggled on its path of implementation, especially when it comes to data-mapping to measure challenges and success. It is the inadequate attention directed towards its monitoring, evaluation and continuous adaptation to the changing needs of the time that its essence has diluted, rendering it mere highfalutin talk on the need to plug the gaps when it comes to public legal education in India. The data on the success of the mission remains unclear. However, what is clear is that the mission needs to be revived in full force particularly as the common citizen struggles to make ends meet during the catastrophic times brought about by the pandemic, which have rendered the citizen helpless and unable to approach the court of law. It is interesting yet irrelevant that it maintains that it is still accessible and approachable and its doors are open to all, even as it takes up modalities far beyond the reach of the common citizen. The effective renewal of the mission will help generate mass support to recalibrate the judicial apparatus to the circumstance surrounding the common citizen and reorganise it to the just cause it was established to pursue in the first place.

What matters today is that the citizen awakens beyond the patronage of the state, for once. Legal education must be a part and parcel of literacy itself and should be extended as much priority as other fields of academic interest. Only then will the broader vision of legal, political, social and economic justice be organically realised. Only when the public is provided with devices to open its eyes to the functions, provisions and obligations of the law, will democracy be embraced by our country in a complete sense. After all, in the court of law, there is no sympathy for one’s willful ignorance. The final revolution for the cause of legal awareness must begin, once and for all, if the virtues of liberty, equality, and justice are to survive so that the spirit of the democratic republic that the Constitution epithets the country with could be kept alive.

Samridhi Chugh is a final-year student of Journalism with Political Science at Lady Shri Ram College for Women.

Interested in exploring the confluence of law, policy and print media, she tends to use the written word as a conduit for her scattered emotions.

She aspires to pursue legal journalism at a near future.

This site is mostly a stroll-via for the entire data you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and you’ll positively discover it.

I have been browsing online more than 3 hours as of late, yet I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It?¦s lovely price enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you probably did, the web might be a lot more helpful than ever before.

Undeniably believe that which you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the net the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I definitely get annoyed while people consider worries that they just don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side effect , people can take a signal. Will probably be back to get more. Thanks

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this web site. Studying this information So i am satisfied to show that I’ve a very just right uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I so much unquestionably will make sure to don¦t fail to remember this site and give it a look regularly.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I have truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

Hot curvy MILFS, hardcore PAWG cuties and Latina goddesses just about all have a

location here. Will you emerge as an bare husk, tuckered out of all your cum?

Probably. This will be one of the movie categories that split the adult men for the guys and just a authentic,

challenging banging girl can deal with booty of

this value. Observe these beauties in sinfully alluring single carry out, in one-on-one gender or in teams as well!

If this booty can suit into frame, we’ll

showcase it for your fun. Put together your ideal playlist that’s made totally of babes with thick asses and a whole lot of banging attitude.

At hand show alternatives situated on movie play-back pages also

produce it uncomplicated to experience attached.