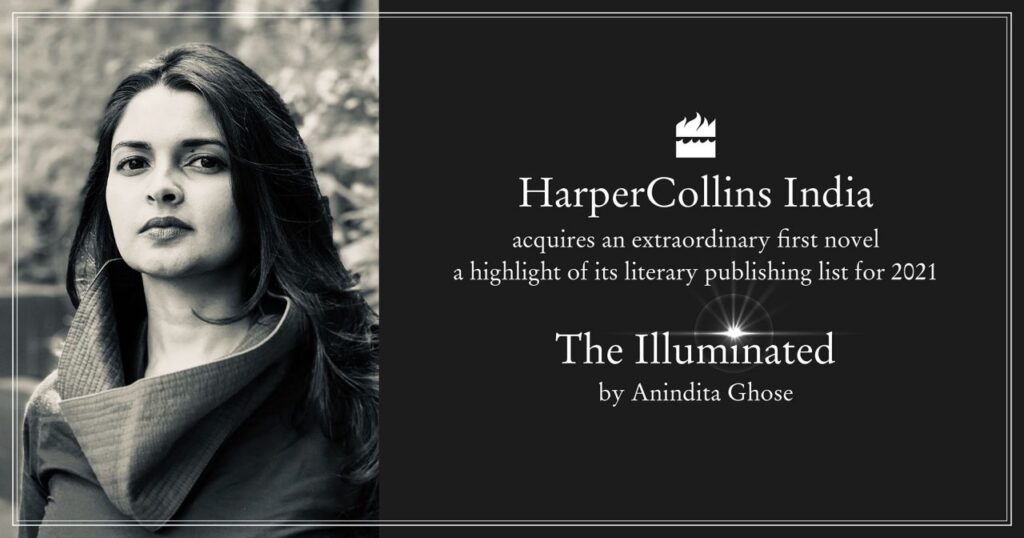

The idea that the personal is political has now underpinned feminist thought and action for decades. It is this very idea that Anindita Ghose has fictionalized in her debut novel ‘The Illuminated’. The title itself foregrounds the central theme of the novel i.e, a new way of seeing. It is also perhaps a reference to the culmination of the journey of self-discovery undertaken by the two female protagonists of the book – Shashi and Tara, a mother-daughter duo – that renders them ‘illuminated’. Ghose, through her novel, has used the moon and its phases as a trope for tracing this journey of self-discovery. Apart from the two protagonists, a third, bold, confident and lively character emerges in the form of Poornima, Shahi’s domestic help.

The book deals with themes like grief, love, familial relationships, self-discovery, patriarchy and hope. However, these otherwise conventional yet evergreen themes have acquired a greater emotionally potent force through their contextualization in a political-social reality; and the use of poetic language enhanced with interesting metaphors. Above all, the work is steeped in Indian mythological and cultural narratives that aid the reader to anchor themselves in the world of the characters.

The novel is set in the context of escalating right-wing religious fundamentalism that seeks to reverse the ‘degradation’ of women engendered by western influences, and in turn, protect them. This context has been weaved with a visceral narrative catalysed by the sudden death of Robi, Shashi’s ideal but emotionally absent husband, and Tara’s doting father. Robi seems to be the centripetal force in their lives. The story, simply put, is about how Shashi and Tara navigate through the unexpected ripple effects that Robi’s death creates, on one hand, in their personal lives and, on the other, in their relationship as a mother and daughter.

After Robi’s death, Shashi finds herself feeling untethered, overcome by a sense of loss of self. In the face of her husband’s death, an angry and distant daughter, and a son who is oceans away, a haunting and disconcerting awareness gradually seeps in; Shashi realizes the extent to which her life has not been her own and how her identity, over the years of her marriage, had receded into the darkness, overshadowed by her husband’s charismatic personality. While Shashi, as a graduate in philosophy, is well-versed in the works of Hegel, Adorno, Aurobindo and the likes, these learnings only remain limited to her classroom; at home, and in the public sphere, while this makes for a praisable quality in a Bengali wife, her identity comes to be determined by Robi.

With clever use of words and personification, Ghose expresses this in the voice of Shashi:

“A degree in literature or philosophy was the mark of a girl from a good family. Study Sociology and there is the danger of becoming the kind of activist who wears sarees without starch and her hair in an angry knot”

That is the purpose Shashi’s degree was meant to fill, and like many other women, she chooses, or more bluntly, is compelled into abandoning her career in academia and pursuing a life as a mother and caregiver.

Hence, Shashi’s character presents what Saloni Sharma in her review published on Scroll has described as “an insightful study of the limitations imposed on women’s lives in privileged households”.

These circumstances, which have left Shashi widowed, acquire greater stakes amidst the rising religious extremism. As a recent widow, Shashi comes under the radar of the MSS – Mahalaxmi Sevak Sangh, an organization created by Ghose as the face of this extremism – and their ‘laxman rekha’ campaign which warns against the dangers of women living alone, and strives to place single women under a male guardian for their ‘protection’. An idea dominant in Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’, and one that seems eerily possible in today’s political environment.

In contrast to Shashi, Tara, her daughter, a fiercely independent and stubborn Sanskrit scholar, is the star or tara of her father’s world and heroine of her own; a world of privilege, erotic Sanskrit poetry, mythological narratives paralleled with reality, and abhisarikas who exist beyond the realms of Brahminical patriarchy and are not shy in their pursuit of desire. Tara strives to be this abhisarika but teeters dangerously close to transforming into Kalidasa’s submissive version of it – which her character emphatically denounces – when her love affair with an older man comes to a turbulent end. This event plays a momentous role in Tara’s journey of self-discovery. In retrospect, Tara’s initial anger is replaced by a struggle to come to terms with the exploitative nature of their relationship as she questions her compliance in it. Through this narrative, Ghose has confidently dealt with the complex and explosive dynamics of consent that seem to mark modern-day relationships. She brings our attention to the subtle yet potent difference between silence or passive compliance that manifests itself in the lack of an explicit ‘no’; and an explicit ‘yes’. Through Tara, Gose has also explored the depth and historicity of a woman’s anger and power that stems from it. She writes:

“There is something curious about a woman’s anger. A spark can set alight a whole forest, once wet and green. And it burns and burns, fuelled by the memory of past injustices borne not just by them but the women before them – their mothers and grandmothers, sisters and aunts, friends and maids, the women in stories, witches, princesses, queens and goddesses”.

The Illuminated is also a work of hope, a silver lining in the cloud that manifests itself in the form of a fictional political thought experiment – Meenakshi. Meenakshi, named after its founding woman, is a feminist state which challenges the growing power of the MSS in limiting women’s agency. It is Poornima’s courage to imagine a space for women and dream of a more liberated life that encourages Shashi to move with her to Meenakshi and open her own school – a moment of reunion with her true self, and departure from the Shashi of Robi’s marriage and society. Ghose also gives voice to the power of imagination and experiment as she writes in Shashi’s voice:

“We have to have the courage to explore extremes. It’s the only way to arrive at the centre… Meenakshi is not a fantasy. There is a long history of communities around the world banding together for a purpose, exploring radical ways of living”.

What stands apart in this book is the way Ghose has used grief. Grief is a theme that is not uncommon; many writers over the course of centuries have dwelt upon it, trying to grapple with this amoebic human emotion and producing moving, heart-wrenching narratives. While grief, in Ghose’s work, might lack this dramatic character, it deals with the subtleties of it, its blackhole-ish yet life-giving nature; in the different ways it manifests – as Shashi’s epiphanies, and Tara’s anger and disbelief that makes her distance herself from her family. Yet, at the same time, by contextualizing grief in a socio-political context, Ghose touches upon the complex relationship between grief and women; a relationship coloured and subverted by factors like exploitative and oppressive patriarchal norms articulated in funerary rituals, and the long history of the alienated widow, who at one point in time was forced to burn with her husband.

The story is simple enough and easy to follow; however, in its simplicity, it has managed to accommodate and grapple with many issues like these that concern women’s lives and don’t get enough attention. Ghose has managed to uniquely use the themes of grief and relationships to highlight the trap of self-effacement that women are often compelled into. These are important struggles that Ghose has gravitated our attention towards; a reminder that the fight is not only with the tangible shackles of chains that bind us but the veiled threats that inconspicuously corrode our lives.

Being an art and culture enthusiast, Sumira is an avid reader, a passionate dancer and a curious writer. She has a keen desire to learn and feels strongly about the issues of diversity and inclusivity. She finds solace in food, music and the company of her friends.

Really clean site, regards for this post.

I adore studying and I conceive this website got some truly useful stuff on it! .

Right now it sounds like WordPress is the preferred blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Thanks, I have just been looking for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what in regards to the bottom line? Are you certain about the supply?