The colonial-era remained witness to a hoard of multifaceted developments sprouting as apertures to aid the apoplectic Indian public. The onset of print culture across various languages in the 19th century was instrumental in bringing public opinion into the mainstream national discourses. An essential element of this was the enthralling paraphernalia of debates, reform movements, legislations etc. around the women’s question that captured the plebeian audience including the functionally literate female readership. Various literary genres like didactic prose autobiography, editorials, journals etc. Became central that offered insights on assorted themes, none of which can be hermetically categorised as emancipatory or otherwise because they served diverse purposes according to contingency and convenience, a trajectory that most vernacular print materials followed.

To a certain extent, a percentage of these print material edited by both men and women (since generally no other gender/sexual category acquired explicit space in the popular imagination) devoted considerable latitude to conversations, letters, opinion pieces etc. to themes like women’s education, their and sexual validity outside of procreation, right to a dignified life after widowhood, etc. was liberatory to an extent, but to accept the proposition entirely at face value, wouldn’t bring out the complications embodied in it. With the growing visibility of women in the public fora like national movement, women’s associations etc., magazines, biographies, periodicals, personalised letters etc. across languages like Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Urdu etc. became mouthpieces of middle and upper-caste women to raise questions on imposed ideals, highlight social evils, espouse equality, women’s rights and encourage role in national movements, contemporary politics, news etc by recognising women as individual subjects with an independent identity. Women contributors’ experiences added an ounce of veracity and appeal to the issues raised.

Such radical ideas manifested, for example, in vernaculars like Tamil magazines namely Pen Kalvi, Kirahalakshmi etc. where narratives focussed on addressing emotions of love, pleasure, companionship, sexuality among couples and even widows beyond procreative purposes, a remoulding of social norms based on caste, religion, etc., staged scathing attacks on non-companionate and transactional nature of marriages, dowry, etc. In Bengal, The educated bhadramahila community fashioned and claimed shares in regenerating the social system by building a communicative space through print facilities through which it stressed the need for equality in the curriculum of both boys and girls since running a home needed equal prowess in accounting, administration judgement as running offices. This basically happened through magazines like Bharati, Antahpur among others and a further sense of personal expressions seen in the autobiographical writings of Sarala Debi, Krishnabhabini Das etc which added to the veracity of the issues that were vocalized.

If seen in this light, the print had liberatory ramifications as it supplemented the inadequate and skewed education received in schools, helped forge a sisterhood outside domestic spaces and rope in the reading audience in a thread of similar goals, impressed upon the mixed readership to ponder on the issues raised and kept them abreast of various developments. This exposure to diverse information empowered and inculcated a critical and intellectual consciousness in the way women lived, felt and acted.

Questions of respectability in the family before and after widowhood, the endowment of women with individual characteristics as men, negotiations for access to public spaces, employment etc came to be reconsidered. Cheap prints like almanacs, novels etc in colloquial produced titillating pieces which clandestinely made way to the antahpura, that helped supersede the imposed monotonous codes of virtue, to provide unimaginable pleasures, satiation, gave an informal space to some homoerotic writings and helped escape the plight of being desexualized after procreation and motherhood by reading. From the archival perspective, vernacular print literature helps to recover the female voice, that is glossed over by official records.

However emancipatory they might sound, the aforementioned phase drew upon apparently reformist foundations in print that claimed to address women’s question, with mixed editorship, only to refurbish their traditional gender roles expressed in terms of family and household. This was educational as it helped, in tandem with religious ideals and Victorian values of obedience, thrift etc., to produce efficient, functionally literate mothers, English speaking yet pativrata wives, housekeepers, cooks etc. This influence could never be done away with and most print materials juggled and struggled to balance their content comprising popular ideology and reformatory material. Some writings manifested a stint of revolutionising ideas but were nipped when they transgressed generated codes.

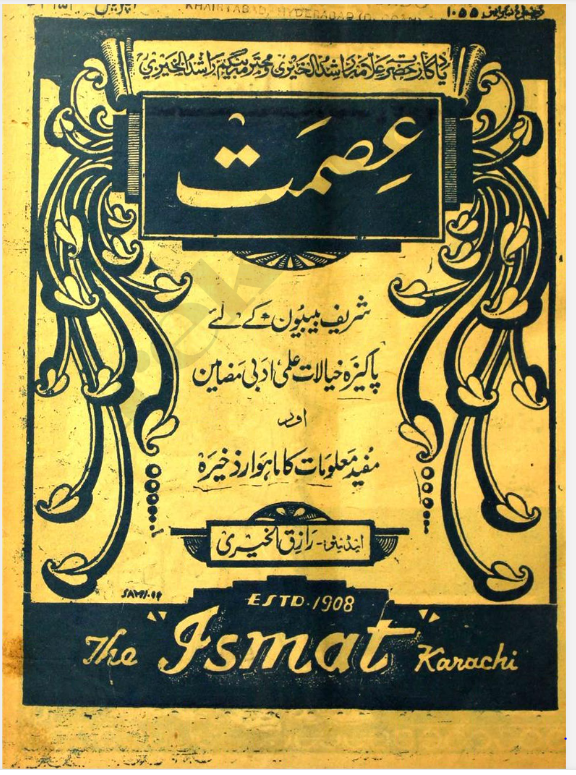

Women contributors usually spoke within gendered and moral confines associated with womanhood when they acknowledged the need for education, rights, awareness, activism etc to benefit family, witnessed in writings of contemporary autobiographers like Hironmoyee Debi, Hindi and Urdu magazines like Chand, Tehzib, Khatun etc. This was presented in the name of service, sacrifice, for the nation, nationalism and society and not as an ambitious claim to have a career outside the household. Moreover, they didn’t address the agony of lower caste, working-class women who were seldom literate.

Yet it is vehemently true that print culture initiated a process of liberation and opened floodgates for women to vent, reflect and argue their cause. That the growth of such a female readership aroused anxieties in the male-centric society is beyond doubt since empowered women often raised uncomfortable questions that society had no explanations for.

From Dhanbad, a history graduate from LSR. Currently a first year Masters student in Delhi University. I religiously experiment with cuisines! I spend my free time drooling over fictional characters and listening to music. Personally follow and urge everyone to follow the 'live and let live' principle in life. Current Role: interning with ITISARAS as a writer. Ultimate goal: To help create consciousness about animal-welfare and be of help in the strive for universal education. Biggest achievement: helping an adolescent with no educational background learn the basics of language, to read and write. Educational Qualification: History graduate, currently a Masters student at Delhi University.

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly feel this website needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the information!