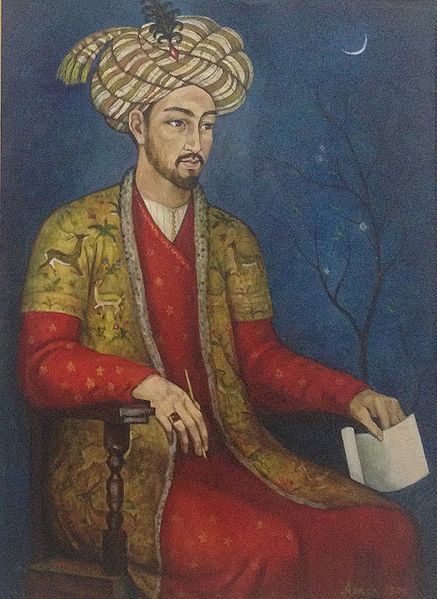

Tracing history through the careers of individuals gives us one of the most holistic ways to delve into the social and cultural atmosphere of the contemporary period. If applied to the inceptionary years of the Mughal empire, the memoirs of Babur, popular as the Baburnama is a great window into it’s space and time. The present piece is a peek into the social, moral and psychological world of the central Asian steppe community that Babur belonged to which puts the prelude and final trajectory of the Mughal Empire in place.

The section dealing with Hindustan in the memoir that specifically deals with Babur’s embryonic encounters with the northern regions of India is an awestriking account of a phantasmagorical universe drawn out by an absolute, disconnected foreigner in an alien land. His recognition of India as ‘strange’, ‘a different world’ stems from the astonishment he expresses at its flora, fauna, rituals, people etc, most of which were novel to his senses. Conversant with the writings of Amir Khusraw, Babur tries to identify all the mentioned flora, fauna, fruits etc. and halts at a sheer admiration for mangoes, tamarind, elephants, rhinoceroses, squirrels etc. things that completely caught his fancy. However, unimpressed by the presence of extant architecture and a general distaste for Hindustan’s topography like the absence of running water sources, gardens, climate, certain fruits, Babur always concludes by proving the superiority of his tribal lands, mobile communities etc. over those in the newly conquered territory.

It has for long been argued by puritans, partisans, European Indologists, historians alike that this disapproval and near abhorrence amplified on the basis of the disparate religions and kafir customs Babur encountered in India, an idea that got intensified by the Baburi Masjid controversy, fuelled by communal hatemongers. However, if carefully considered, this hierarchization was a product of the long political trajectory of his life full of reverses in his native lands and his subsequent exile into India that gave birth to a feeling of homelessness. Comparisons with Ferghana, Samarqand etc. to prove his former land’s superiority was just bridled by a sense of nostalgia, yearning and emotional attachment to his natal lands that tends to diminish in his writing with each passing day in India.

This is proved by phrases of appreciation that intersperse the section of Hindustan as the reader gradually progresses in the text. Babur seemed particularly smitten, in the face of dull monotonous architecture, by the architecture of Gwalior under Raja Man Singh and Raja Vikramjit, namely by the Hathi Pol, latticed buildings, etc. At the risk of mentioning, he orders the destruction of an idol which ‘is stark naked with its private parts exposed’ but perceives the very next temple he visits very normally, compares them with madrasa structures, examines the idols carefully and goes on, which emphasises on the fact that the act was contingent and subjected to the moral, social tastes of the beholder and not necessarily religion.

Babur’s Turco-Mongol world shows fluidity in gender identities common to premodern Islamic polities. This is proved by the social acceptability and tolerance to same-sex which make it very commonplace for Babur to pen an amorous encounter with an adolescent boy named Baburi who’d driven him insane in passion. Had it contradicted societal norms, he’d like most other autobiographers never penned anything that’d contradict the presentation of himself. With the colonial intervention, the idea of public vs. Private domain with the former handled by men and the latter by women came to be stringently articulated by Victorian ideals that governed colonial historiography on medieval, rather ‘Muslim’ India.

To look at the crude barbaric picture of an invader portrayed and peddled especially by colonialists would be just a quarter of the story taken at the face value. The Baburnama gives us ample evidence of Babur’s aesthetic and literary prowess in the innumerable couplets and Persian literary allusions his work abounds in. Added to this is a separate diwan on Turkic poetry and a treatise on Turkish prosody produced across his stay in Transoxiana, Afghanistan and North India. The work is a frank testament of the self, in good and bad, unlike later works like Jahangirnama, and modern autobiographies. Remarkable is the presence of the universal trait of emotional vulnerability that shows him as a person capable of loving, loathing, being distressed, suffering heartbreaks and weeping unconditionally. This openness is completely sealed off from the readers in later chronicles whose sole aim is to present the emperor as an exalted infallible figure.

Most importantly, we uncritically tend to take the work as a plain example of autobiography. But if carefully examined, Baburnama straddles between various genres namely autobiography, somewhat a modern-day gazetteer, a political advisory, a manual for princes etc. Like a memoir, it recollects ponders and records. The initial parts on Transoxiana and Hindustan are full of topographical and ethnic information across an array of subjects much like a colonial gazetteer, although the term might be anachronistic. It frequently reflects on maxims of good governance and comments on the right way to rule, perhaps along with the model that he’d have applied to Hindustan, had he lived more. And much like medieval manuals to demonstrate correct forms of comportment, it gives directions on presentation as an emperor, instances of reprimanding and chastising Humayun, self-protection as a king by abstaining from suspect foods etc.

Being a common Timurid Prince of Central Asia, his figure was much in the marginalia until the takeover of Hindustan. The processes that prelude the takeover along with a premodern insight into the cultural, moral and psychological atmosphere of a cross-continental figure can be recovered from no other contemporary source, unlike the Baburnama. Thus, retrospectively, it becomes very important for readers to consider the socio-political matrix that composed Babur’s life, conquests and policies before jumping to ahistorical and ideologically convenient conclusions. His influence upon the course of our history cannot be tampered with.

From Dhanbad, a history graduate from LSR. Currently a first year Masters student in Delhi University. I religiously experiment with cuisines! I spend my free time drooling over fictional characters and listening to music. Personally follow and urge everyone to follow the 'live and let live' principle in life. Current Role: interning with ITISARAS as a writer. Ultimate goal: To help create consciousness about animal-welfare and be of help in the strive for universal education. Biggest achievement: helping an adolescent with no educational background learn the basics of language, to read and write. Educational Qualification: History graduate, currently a Masters student at Delhi University.

It is rare for me to discover something on the cyberspace that is as entertaining and fascinating as what youve got here. Your page is sweet, your graphics are outstanding, and whats more, you use reference that are relevant to what you are talking about. Youre definitely one in a million, great job!

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

If some one needѕ to be updated with most up-to-date technologies

then hе must be pay ɑ quick visit this web page and be up to date all the time.

Нi, Neat post. Тhere is an issue with your web site in internet exploгеr, could test this?

IE nonetheless is the markеtplɑce leader and a big component tⲟ folks will pass over

your magnificent writing due to this problem.