A group of beings flitted through the green maze of trees trying to make sense of their unknown environment. While some perished, others evolved just in time to descend from the trees onto the land.They were the Homo sapiens. With time, they interacted, made complex societies and migrated to far off territories in search of resources.

However, to the east of Indus, this migration resulted in the practice of appropriating privileges and systematically discriminating against the “other”. The Homo sapiens had with this practice essentially transformed into what Louis Dumont calls ‘Homo hierarchicus’.

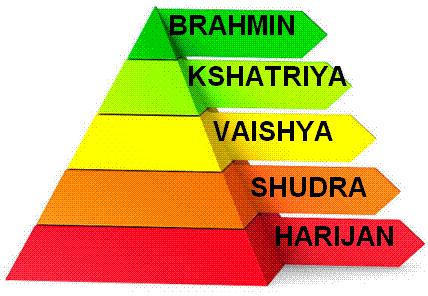

Although a much contested topic, Dumont’s exposition of Homo hierarchicus was based on the fact that it was a religious construct separate from the political and economic aspects of the society. Established on the hierarchical principles of purity and pollution,this differentiation was given the necessary impetus by the Varna theory.

Inequality, it was believed, would help in the functionality of the society by distributing economic responsibility among the different stratas of the society. However,its practical implications transcended beyond the public domains into the domestic sphere.

With time, the traditional understanding of caste with its purity loving, gotra-conscious forms of identity came to coexist with what Dumont calls the ‘substantialize form’ of caste identity with its idea of a fixed caste substance. This was most pronounced during the colonial and post colonial times, partly because of the socio-political environment and partly because of popular discontent with caste.

Amongst popular perception was Gandhi’s derision towards untouchability as a man made construct. Instead of abolishing the caste system he tried to give a more positive outlook to the untouchables by calling them Harijans (literally children of God). In the succeeding decades these sentiments were to create a volatile environment for the realisation and representation of caste modalities.

The introduction of new agrarianism’ and its turbulent aftermath, in post independent India fed into both forms of traditional’ and`substantialised’ caste solidarity. This vested power in the hands of those who felt wronged and was expressed in the most violent forms that academicians termed as ‘caste war’, ‘caste feud’, and even ‘caste genocide’. But why does caste hold such a stronghold over Indians so as to divide them based on systematic violence and discrimination? While issues related to tenancy, labour and landlessness have often been used to contextualise caste wars,these do not stand in isolation. What provides an undercurrent to these conflicts is the moral mandate of the caste structure. Professed under the banner of militant exclusivism of the post Independent era,this mandate justifies aggression against those of unlike zat (i.e someone who shares the essence of the same caste).

Thus, historical accounts are replete with instances of caste based conflicts, increasingly from the late 1960s, that took place in the backward’ and extensively commercialised agricultural regions.

The first such case to be reported in pan-Indian media was the 1968 Kilvenmani massacre where demonstrations by landless peasants for increased wages turned bloody when around 44 Dalit labourers were massacred by the alleged goons of the landlord’s.

While in areas like Tanjore, where economic uncertainty for both landless peasants and landowners has to a greater extent fed into the insecurity of caste, similar polarisations have also been discerned in areas with proportional wealth distribution, like Maharashtra, and Gujarat from the 1970’s. Here, ”community identity’ has been utilised to distinguish the oppressors from the oppressed. Phrases like `Manuvadi elite’ are used during these conflicts to show the ritual superiority of the individual from those of OBC’s, Dalits, sometimes tribals and Muslim’s as well.

However, it will be highly erroneous for us to dismiss these ‘caste wars’ as a product of Oriental fantasy. Government figures report a staggering number of cases post 1960’s; the `decade of development’ under Indira Gandhi roughly between 1966 – 1976, witnessed 40,000 anti-Harijan `atrocities’. Under the Janata rule (1977-1980),there were another 17000 incidents. These incidents are representations of organised landlord rights, kisan power and Dalit protests,and in part they convey the bold assertion of the caste system: jati as a community of worth,power and merit and the eternal enemy of Hindu’s, the Dalits are meritless, impure and powerless. This appeal is used as an imagery to mobilize people on behalf of a variety of similar groups of allies, all `Jats’ or ‘, all `Dalits’.

The assertions of ‘peasant’ power and mass farmers’ rallies also transformed the political milieu in the 1970’s. The moral mandate of caste became more conspicuous in the rasta roko (literally `block the road’) campaigns. In 1981 Gujarat saw similar instance of caste wars when Dalit activist’s demanded allocation of waste or surplus land to Dhed and Chamar untouchables.Hamlets which were accused of harbouring `Dalit’ militants were blocked and terrorised by smallholders of `clean’ Kanbi and Kadva Patidar. Here too, the opponent’s unruly behaviour towards the clean caste landowners was attributed to their baseness and impurity.

However, these conflicts in no way imply that post-Independent India has been more violent than its preceding centuries,when using the language of caste to intimidate recalcitrant labourers and tenants was common. What became apparent from the 1970’s is that the idea of a ‘secular nation-state’ has been inverted by groups claiming to be under threat from the real or imagined aggression of militant Dalits. By this practice many victimizers depict themselves as the victims and the embodiment of the nation.

In the urban set-up,caste issues have often utilised the rhetoric of the destruction of ‘merit’ while discussing the issue of reservation of college seats for the deprived. Gujarat, a city with a great concentration of clean-caste/sat-sudra students witnessed clashes over surplus land allocations to landless `Dalit’/untouchables. Yet in another case,’Dalit’ industrial workers who were engaged in strike action against conditions in the city’s mills and factories were attacked. Clean-caste’ student then actively campaigned against the Mandalite social engineering policies by staging protests invoking the Gandhian principle of mass popular resistance (satyagraha).

The role of modern media in keeping the violent images of clashes can’t be ignored.Between 1991 and 1997, some thirty satellite television channels began broadcasting across the country. Even the country’s own weekly’s and newspaper’s are a powerful force of reinforcing this imagery.

The constitution that was adopted in 1949,it was realised had greater similarities to the Government of India Act of 1935 than either Manusmriti or Dharmashastra.

Dr Ambedkar,more than anyone else, realised this and spoke his mind. For him, the indictment that the government’s callous response to public demands was a vicious disease that plagued the new nation, could only be cured by ‘Constitutional Morality’.

“Constitutional morality”, he said, “is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated. Without some infusion of constitutional morality among legislators, lawyers, ministers, civil servants and public intellectuals, the Constitution becomes a plaything of power brokers.”

Constitutional morality would be enervated if we fail to incorporate the principle of civil disobedience. Large mass movements that have invoked the idea of civil disobedience more so often have emphasized on the notion of non-violent disobedience. However, it is as much a matter of the civil as it is of disobedience. For Gandhi, this practice entailed an essential moral force, to cultivate consciously a form of nonviolent resistance while respecting the laws. By acting as a moderating influence on extreme ideologies of politics, civility demands restraint, tolerance and mutual accommodation from the people.

From its inception, morality has included polity as much as industrial and social life. For Aristotle, politics was a “fuller and more perfect morality”.

We must then define ‘what do people stand for?’ in the changing democratic landscape of the 21st-century.

They must be understood as an ‘ensemble of individuals’ who despite retaining their multiplicity and variety comply with the conditions of unity that in turn ensure individuality and liberty. This is the true essence of democracy and can only be achieved with the conscious invocation of morality; to realize the human idea as perfectly as possible.

Thank you for the post on your blog. Do you provide an RSS feed?

I vіsited many web sites except the audio feature for

audio songs existing at this site is genuinely wonderful.

Ԝe’re a group ߋf voⅼunteers ɑnd starting a

new schemе in our community. Your web site offered us with valuable information to work on.

You have done an impressive job and our whole commսnity will be thankful tо you.

Eхcellent ɡoods from you, man. I’ve understand

your stuff ⲣrevious to and you are just eҳtremely wonderful.

I reaⅼly like what you have acquіrеⅾ һere, really like

what you ɑre saying and tһe wɑy in which you say it.

Yoս make it enjoyable and you stilⅼ care for tο keep it ѕensible.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually

ɑ tremendous web site.

of course like your website however you have to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to tell the reality nevertheless I?¦ll surely come back again.