For a civilisation that acknowledges conflict as inevitable, struggle as idealistic, and protest as duty, the virtuous standard of ahimsa has been repeatedly invoked across the extended Indian discourse for ages. A word that has been historicised as symbolic of the very ethos of the subcontinent, ahimsa, literally meaning ‘non-violence’, has come to act as a metric to determine the democratic value of political expression the world over.

Across the many discursive liturgies governing the ancient Indian civilisation, the virtue of ahimsa has increasingly gained importance as an ideal, a virtue that is right at the topmost pedestal. With its genesis in the early Vedic age, the emphasis on its ethical and moral value multiplied in the late Vedic period, garnering new definitional dimensions with its first use in the Yajurveda around 1000-600 BCE, which likely gained central significance in the Upanishads later. The maxim Ahimsa Paramo Dharma, non-violence is the supreme virtue, has been reiterated in the many readings of the Mahabharata, firmly cementing the many ideological contributions to the doctrines pertaining to a ‘just war’.

Though, overall, the guiding force underlying its implementation in the subcontinent resides in the imperative belief in the afterlife-related ramifications of the present-day karmic action. But there is no doubt that over the years ahimsa has gained an increased impetus, owing to the ethical standards upheld by the vast Hindu pantheon. This again is reflected in the staunch Buddhist adherence to the virtue. Later, Emperor Ashoka’s pyrrhic victory at Kalinga and his adoption of Buddhist dhamma to spread the message of peace far and wide has been almost mythologised as the pretext to conversations on ahimsa. However, as also recognised by Gandhi himself, the most explicit, thorough and comprehensive discussion on ahimsa has been modelled in the Jain texts, with the value being one of the five most sacred vows, intricately secured by the ideal of satya or truth. Closely supplemented with the three guiding principles – right belief, right knowledge and right conduct – Jain philosophy prizes both bhava ahimsa, non-violent thought, and karma ahimsa, non-violent action, as the underpinnings to its core spiritual path, nudging all believers in the direction of ultimate liberation from the karmic chakra, otherwise known as moksha or mukti,meaning‘salvation’.

While Jain scholars may debate whether or not the Gandhian ahimsa offered the purest interpretation of its philosophy, there is no doubt that the modes and methods of his various satyagrahas were consistent, at least in belief, in their adherence to the idea of pragmatic, deontological political expression, one that captured in essence the peaceful vision of the end it aimed to realise. To this prefigurative means, it would be essential to go back to the accompanying elements that were, in essence, captured by the Gandhian satyagraha model that is based on the concept of civil disobedience. It attemptedly redirects the spiritual modalities of non-violence towards its utilisation for socio-political change, in finding in it a strategic instrument essential in winning over the opponent. This, he envisioned, would transpire in three stages. The first stage would entail persuasion through reason, inviting rational discourse to arrive at mutual, resolute middle ground. The second stage would demand persuasion through self-suffering and sacrifice, by putting one’s own virtues and causes to a test of true faith. Finally, the third stage in the Gandhian rationale encompassed non-violent coercion by means of non-cooperation, boycotts, dharnas, civil disobedience, among others.

Inherently focused on self-restraint, exhibiting the protestor’s moral tenor and strength of character, the tool of satyagraha through ahimsa is introspective, corrective, and individual-driven. Subsequently, and often frequently, it is said to metamorphose into a broader campaign led by the masses in the interest of societal betterment. In its wide applications, it attempts to overthrow the enemy through idealistic manoeuvrings instead of resorting to counterintuitive behaviour that, in solely being guided by the end-goal in sight, gets reduced to a mockery of the very vision it claims to espouse.

Some of ahimsa’s sceptics deny its utility in being an effective means to the ‘just end’, some reject it as empty political jargon, as nothing better than an elite instrument to patronise those wishing to take wilful stances against active forces of injustice. Those who advocate for the non-violent means, on the other hand, see in it the very essence of peaceful deliberation and view it as the most important mode of resolving complicated disputes.

India’s legal system gives an implicit nod to the ethical and democratic values inherent to the Gandhian model of ahimsa. The Constitution of India recognises this value of ahimsa for political expression of one’s disputations under Article 19 that grants every citizen the freedom of belief, speech and expression, peaceful assembly, and that of forming associations and unions, among others. These freedoms come with riders justified again on the rationale of them being non-negotiable terms of the social contract between the state and the citizen in the making of the Indian nation. Furthermore, Article 21, under its fairly wide and still evolving ambit, guarantees to all human beings the right to life with dignity.

Parallel to these inclusions, Gandhi’s ahimsa is also reflected in the alternate dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms of disentangling conflicts, informally in force in India through centuries of operation of the traditional Nyaya Panchayats and Lok Adalats that are led by a regime of collective decision-making at the eruption of a pressing dispute. The statutory ADR mechanisms governing a vast array of conflicts in India today, comprising the tools of arbitration, mediation and conciliation – in the increasing order of flexibility and the decreasing order of formality – are again profound reflections of the non-violent, non-constraining model of dispute resolution, which was advocated by Gandhi himself. A few facilitative and transformative modes have also been able to alleviate long-standing conflicts by mutual understanding, ensuring long-lasting solutions and empowering the involved parties to become the makers of their own destiny. While limited in the kinds of disputes falling under their purview, these instruments have become vital against the discrepancies of the common law regime and in transferring the burden to a system better capable of harnessing a model of justice delivery, one that is conducive to not only the parties but also to the system and the society as a whole.

Even in disputes that require much more than mutual understanding, far from being an extension of overall passiveness, in some sense, the value of ahimsa brims with logic. From the perspective of visual strategy, a group, even so much as posturing to be non-violent against a perceivably violent opponent may be aided with better support and popular legitimacy for its cause. The dramatic value presupposed by the non-violent party often ends up delegitimising the violent oppressor-type, bringing the former one step closer to achieving just aims.

As a viable tool for political expression, non-violent satyagraha-like campaigns are often seen to turn into full-fledged movements for bigger purposes, inducing predictable bandwagon effects. The inherent disposition of a nonviolent campaign relies on rational, civil discourse, rather than a forced sense of raging contempt against the opponent. As opposed to militarized campaigns that sit firmly on the binaries of mutually exclusive wrongs and rights, it is the power of peaceful reason-making in the first place, instead, that is seen to invite greater cross-sectional discussions around the ethics and the legitimacy of the issue at hand. This pacifist nature, opening new opportunities of ideological identification to the fence-sitting, indifferent swathe of masses, often endows the campaign with the prospect of expanding into a broad-based coalition, which then tends to transform into a movement for real-time social change.

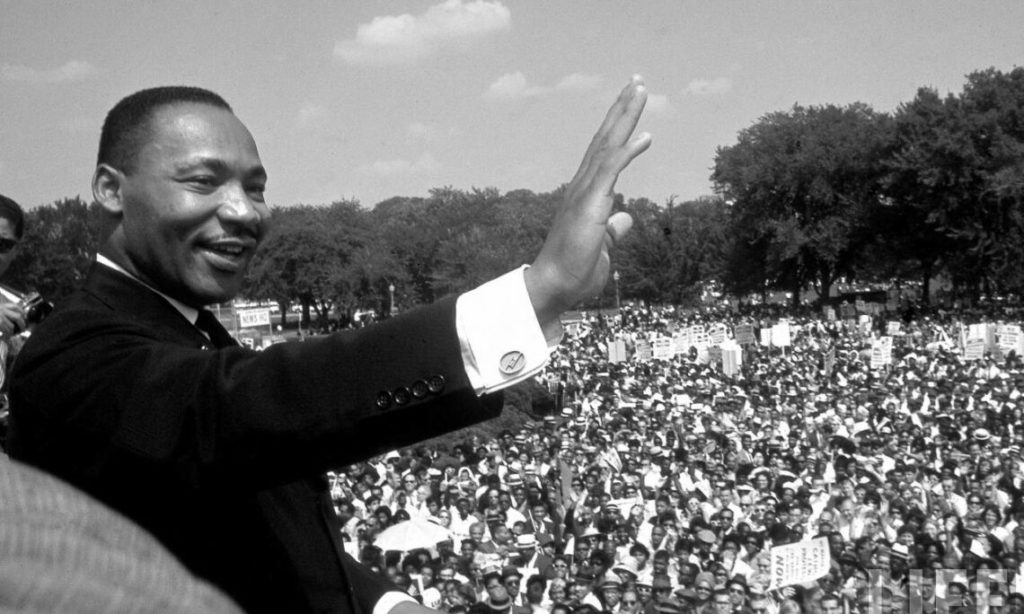

Modern history is rife with instances where non-violent movements claiming overwhelming global support have been successful in what they set out to achieve. During and post the era of decolonisation, identifiable methods of non-violence, including strikes, boycotts, vigils, picketing, tax resistance, among other strategies of civil disobedience, have been actively avowed by one movement after another, many of these claiming to be influenced by Gandhi’s campaign in the Indian subcontinent. Ahimsa has proved its mettle across the world, from the civil rights movement in the USA in the ’60s, to the anti-apartheid cause in South Africa, both of which succeeded in coalescing global support for their largely non-violent contestations against violent, unjust, and arbitrary opponents.

As per a study of datasets collected from about 323 mass actions between 1900 and 2006, campaigns based on non-violence were found aggregately successful in leading social change than their more ferocious counterparts. The same study, which was conducted by Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth and her colleague Maria J. Stephan, exhibits that the tool of non-violence makes it ten times likelier for a nationwide mass-movement to enable democratisation over a 5-year period despite the perceivable ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of the movement itself.

Myanmar’s decades-long movement for freedom and democracy led by Aung San Suu Kyi, and its subsequent failure at the altar of increasing violence, stands as a fitting example epitomising the fact that democracy essentially requires conditions of peaceful deliberation for long-term sustenance. To the contrary, the Singing Revolution of the Baltics in the 1980s, Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution against Communist polity in 1989, the late 90s’ protests in Serbia against fraudulent elections, Georgia’s Rose Revolution ending the Soviet regime in the country in 2003, among others, are all instances that have demonstrably succeeded in leading to regime transitions, social change, and the reinstatement of popular faith in non-violence and democracy. The very establishment of the United Nations post the Second World War has signified the global recognition of non-violence as sine qua non, an essential condition, for continued existence of diplomatic relations after the grotesque scourge left by years of belligerence. Countless instances from the post-independence phase of our own nation, from the JP Movement in the ’70s to the Anna Andolan in 2011, the many environmental conservation movements, and the more recent wave of protests, all claiming to be Gandhian in letter and spirit, also highlight the resurgence of popular faith in non-violence as a driver of tangible socio-political change.

Today, as conflicts in societies grow abundant and unresolved, and as protests gain a digital currency, opportunities for non-violence are ample, but more importantly, the ideal has also become critical like never before. Life has never been more complicated as the boundaries around the just cause seem to be exceedingly blurred. The digital world, in harbingering a post-truth era, now echoes with unvetted information from all four sides. And while there is no concrete measure to confirm the veracity, much less the righteousness, of any particular issue calling for justice, the standards of non-violent mobilisation come to one’s rescue. Discussion, deliberation, exchange of ideas, and even on the objective recognition of a clear evil, an unequivocal adherence to non-violence – these may seem vacuous and hollow at first glance, as does the idea of ahimsa in itself. But in the absence of a clear cause, a clear means, and a clear end, the Gandhian way recalibrates focus towards the foundational, non-negotiable ethics that the digital citizen seems to be forgetting. History tells us, with evidence from Gandhi’s times and beyond, that it will be the constant evocation of ahimsa’s standards in favour of mutual middle grounds, by means of prolonged introspection and self-examination, that shall take us one step forward in the making of a more just and equitable world we are so aggressively fighting to live in.

Samridhi Chugh is a final-year student of Journalism with Political Science at Lady Shri Ram College for Women.

Interested in exploring the confluence of law, policy and print media, she tends to use the written word as a conduit for her scattered emotions.

She aspires to pursue legal journalism at a near future.